David Beckworth’s excellent Mercatus podcast series has come out with an interview of Neel Kashkari, who is President of the Minneapolis Fed. (The same interview includes an extensive discussion with vice president Ron Feldman as well, something I’ll cover in a later MoneyIllusion post.)

Kashkari is one of my favorite people at the Fed, and I agree with much of what he has to say. As usual, however, I’ll focus on the few points of disagreement. Here’s Kashkari:

When I travel around my district and I talk about the Fed’s current framework, I get a lot of pushback on our 2 percent target. I can only imagine the outcry if we were to try to raise it to 3 percent or 4 percent, number one.

Number two, so far, we can’t even hit our 2 percent target. If we announced a higher target, 3 percent or 4 percent, or a base-level target, it isn’t obvious to me why anybody would believe us or should believe us.

I don’t think this is right. Let’s start with the phrase “we can’t even hit our 2 percent inflation target”. What does that actually mean? It might mean:

1. We are incapable of raising inflation to 2%, because monetary policy is ineffective.

2. We can control inflation, but our current procedures lead to a consistent bias towards slightly under 2% inflation.

I strongly believe that the second interpretation is correct; indeed if the Fed actually were incapable of pushing inflation up to 2%, then we’d probably be currently experiencing deflation. Instead inflation is quite close to 2%, and the Fed is steadily raising interest rates. They are obviously not “out of ammunition”.

Kashkari’s a smart guy, and certainly knows this as well. So I think he and I probably share the view that it’s the second interpretation that is correct. But what does that imply about a higher inflation target?

Suppose Fed procedures lead to inflation persistently running about 0.3% below the target (perhaps because they treat it as a ceiling, not a symmetrical target). Then an increase in the inflation target from 2% to 3% or 4% would raise the actual inflation rate from 1.7% to 2.7% or 3.7% (assuming the bias stayed the same). That’s not my preferred policy, but it’s certainly something the Fed could do. There’s no reason to suppose a higher inflation target would not be credible in a general sense; indeed why would the Fed announce such a target if they didn’t intend to raise the actual rate of inflation up closer to the new target? Yes, 3.7% inflation is not 4%, but it’s much closer to 4% than is 1.7% inflation.

I happen to oppose raising the inflation target, but not because I don’t think the Fed could hit it, rather I don’t think they should be targeting inflation at all. And if they insist on doing so, I’d prefer something closer to Bernanke’s recent price level targeting proposal.

I think we haven’t decided yet how small a balance sheet we want to return to. I think there are advantages to both a corridor system and a floor system. Obviously, the Fed had a corridor system for most of its history, up until recently, when we adopted the floor system around QE. We think, on the margin, a floor system is somewhat easier in terms of operational complexity, a little lower complexity.

I also see an advantage that, if we are in a low r-star environment, where we could be hitting the zero lower bound more frequently, and we might have to turn to QE in future downturns, then if we’re already in the floor system, admittedly with a smaller balance sheet, maybe it’s somewhat easier to then ramp up QE, as opposed to having to shift from a corridor system to a floor system in the future.

So on the margin, I think there are some benefits to a floor system, but I see advantages both ways.

Here Kashkari is referring to the fact that a floor system involves interest on bank reserves (IOR). This was adopted in 2008, as a way of allowing the Fed to do massive QE without reducing interest rates to zero. Without a floor system (i.e. without interest on reserves) a large QE could drive interest rates all the way to zero. (Of course it could also create hyperinflation, it depends on where the economy is when the money is injected.)

I’m not convinced by the argument. If QE is likely to lead to hyperinflation, then don’t do it. If QE is likely to push interest rates to zero, then you probably want interest rates to fall to zero.

Consider the fall of 2008. If the Fed had done QE without a policy of IOR, then interest rates would have quickly fallen to zero, many months before they actually fell to zero (actually 0.25%). But in retrospect this would have been good. Indeed Bernanke noted in his memoir that monetary policy was too tight after Lehman failed in September 2008, and although he did not say this, it was IOR that allowed policy to be tighter than desired, given that the Fed was doing QE to prop up a shaky banking system.

There is an argument that IOR gives the Fed one more degree of freedom, one more tool to use. But I fear it leads to the Fed trying to do too much—aiming policy at both the banking system and the broader economy. I’d like them to focus like a laser on aggregate demand (i.e. NGDP growth) and not having IOR as a tool makes it more likely that they will do so.

In plain English, if you are doing massive QE to rescue the banking system, it’s a good bet that monetary policy is too tight. The last thing you want to do in that case is make it even tighter by paying banks an above market interest rate to sit on their bank reserves.

And by the way, unless I’m mistaken, the Fed’s policy of paying banks an above market interest rate is also illegal. The Congressional authorization of IOR mandated that the rate not be higher than market rates. But it is higher. (Please correct me if I’m wrong on this legal point.)

PS. There’s much more that could be said about IOR, and I refer readers to the excellent work of George Selgin, David Beckworth, and others.

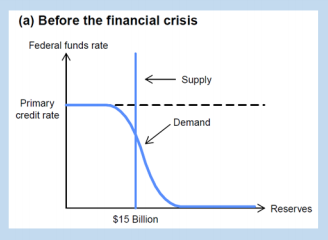

PPS. The following two graphs show the system as it was before IOR was instituted in 2008, and as it looks when IOR sets a floor under interest rates.

READER COMMENTS

Mark

Feb 6 2018 at 7:19pm

When you say ‘aiming policy at the banking system,’ what were their policy goals for IOR regarding the banking system? That by inducing banks to hold more reserves they would make the banking system safer, and just didn’t trust regulators to handle the banking system?

Scott Sumner

Feb 7 2018 at 1:19am

Mark, I think the Fed was trying to provide extra liquidity to the banking system, without actually easing monetary policy.

George Selgin

Feb 7 2018 at 8:49am

Nice post, Scott. Regarding Kashkari’s statement, “if we’re already in the floor system, admittedly with a smaller balance sheet, maybe it’s somewhat easier to then ramp up QE, as opposed to having to shift from a corridor system to a floor system in the future,” it seems to me a good example of straining to defend the floor system. In fact the Fed has to do absolutely nothing to “shift” to a floor system once the policy rate falls to zero. At that point, the opportunity cost of reserve holding itself falls to zero even with IOER=0, and the reserve (fed funds) demand schedule becomes horizontal at the (zero) IOER rate. QE then works (or doesn’t work) exactly as it would in an IOER>0 floor system.

George Selgin

Feb 7 2018 at 9:10am

“Unless I’m mistaken, the Fed’s policy of paying banks an above market interest rate is also illegal. The Congressional authorization of IOR mandated that the rate not be higher than market rates. But it is higher. (Please correct me if I’m wrong on this legal point.)”

The statute says that the IOER and IOR rates should “not exceed the general level of interest rates.” However, in drafting the final rules implementing the 2008 statute, as published in the Federal Register on June 22, 2015, Fed officials determined that for that purpose “‘short-term interest rates’ are rates on obligations with maturities of no more than one year, such as the primary credit rate and rates on term federal funds, term repurchase agreements, commercial paper, term Eurodollar deposits, and other similar instruments (Regulation D: Reserve Requirements for Depository Institutions 2015, p. 35567).”

The specific inclusion of term rates, rather than overnight ones, when the latter are surely appropriate,is bad enough. But the real joke is the presence of the Fed’s own primary credit rate, which is itself always set well _above_ the Fed’s policy rate, and hence necessarily well above the IOR rate. In short, the Fed has redefined the statute requirement so that any IOR rate will satisfy it!

Thus the Fed thumbs its nose at the statute. As I said at the Meltzer event, if that’s not illegal, it sure ought to be!

George Selgin

Feb 7 2018 at 9:12am

Sorry: in the above the statute language should be that the IOR rates are “not to exceed the general level of short-term market rates.”

Alex S.

Feb 7 2018 at 12:25pm

For direct reference here are the links to the law/Federal Register that George references above:

https://www.congress.gov/109/plaws/publ351/PLAW-109publ351.pdf

Bottom of p. 4 of 46

“IN GENERAL.—Balances maintained at a Federal Reserve bank by or on behalf of a depository institution may receive earnings to be paid by the Federal Reserve bank at least once each calendar quarter, at a rate or rates not to exceed the general level of short-term interest rates.”

https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2015-06-22/pdf/2015-15238.pdf

p. 3 of 4 (bottom of middle column)

“(3) For purposes of this section, “short-term interest rates” are rates on obligations with maturities of no more than one year, such as the primary credit rate and rates on term federal funds, term repurchase agreements, commercial paper, term Eurodollar deposits, and other similar instruments.”

Scott Sumner

Feb 7 2018 at 1:31pm

Thanks George, that’s very helpful information. That policy certainly seems to violate the spirit of the law.

Scott Sumner

Feb 7 2018 at 1:41pm

Thanks Alex. That’s helpful.

Rodrigo

Feb 8 2018 at 1:05am

Professor,

A little off topic, l have been hearing a lot of talk that about the tax cuts being an unnesesary stimulus to the economy, causing the fed to “offset” it with higher rates.

Do you believe this will be a case the fed will have to monetary offset inflation? if so would it not contradit the view that the fed is unable to hit its target? What effect would such offset have on the economy? The market seems to dislike it.

I would much apreciate your thoughts on the matter.

PS. Bentley class 08

Vaidas Urba

Feb 8 2018 at 12:00pm

Scott, how is it possible to pay these above-market rates? The market is competitive – what prevents these rents from being competed away? And is there any money-market exception to the EMH?

Matthew Waters

Feb 8 2018 at 5:36pm

Rodrigo,

Scott has talked about monetary offset a lot.

I actually don’t know if monetary offset is the right term. It implies that interest rates are under the Fed’s control. With a fixed monetary target (like inflation/NGDP), the Fed doesn’t actually control interest rates.

Real interest rates are set by the market like any other price. Therefore, the market sets the Fed’s nominal rates as well. The FOMC may set a Fed Funds rate target and IOR, but it will have to correct based on economic data. If it simply refuses to increase interest rates with inflation above target, eventually hyperinflation would result. The dollar would cease to exist.

Increased deficits increase real interest rates due to simple supply/demand. Treasuries are the risk-free dollar-denominated rate and all other securities relate to it. Equities actually have the most interest rate risk, since they are valued as perpetuities. Partly the market drop is explained by increase in real rates.

Matthew Waters

Feb 8 2018 at 6:03pm

BTW, the Fed reserves pre-2008 were $65 billion, not $15 billion, because of $50 billion in vault cash. The Treasury account was also $5 billion, making reserves $70 billion.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/TLVAULT

Fundamentally, IOR is just a change in maturity structure of US debt. Ricardian equivalence would say that this doesn’t matter in frictionless capital markets, complete monetary neutrality, etc.

In extreme, you could make an argument that all US debt should be these overnight T-bills. Before 2008, short-term T-bills took on a liquidity function with settlements done in kind. Overnight T-bills would have T-bills and final settlement in dollars be one and the same.

If all debt was overnight, it would seem like the Treasury is taking all the interest rate risk. But the Treasury also takes interest rate risk on longer-term bonds. In that case, the risk is rates go *down.* How long did the Treasury have to pay 20 year and 30 year bonds issued in 1981?

The more I thought about it, the less there was a slam-dunk case against IOR. There *was* a slam-dunk case against putting IOR in place in 2008, of all times. But in normal times, where IOR is set like Fed Funds rate? That gets more muddled.

Matthew Waters

Feb 8 2018 at 6:07pm

Reading my last comment, I’m realizing “How long did the Treasury have to pay 20 year and 30 year bonds issued in 1981?” is about the dumbest thing I ever said.

Adam

Feb 9 2018 at 3:08pm

Hi Scott,

Interesting post. Like Rodrigo above, I am curious about a mismatch between the recent supply-side growth-oriented tax cut and the much anticipated Fed tightening.

Doesn’t supply-side growth require monetary expansion to achieve the Fed’s 2% target? With AS growth and nominal AD contraction, might the US be headed for deflation?

Best.

Comments are closed.