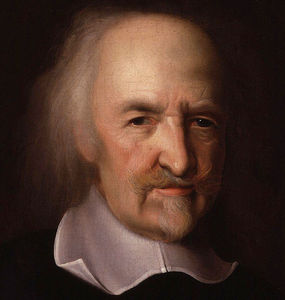

In debates, I’ve had colleagues on the left sneer at me: “You need to read Thomas Hobbes!”

That’s not wrong; we should all read Hobbes. He thought that human quarrels could not be solved by promises to cooperate. His 1651 summary was pithy: “Covenants, without the sword, are but words and of no strength to secure a man at all.” Hobbes thought that the only way to assure cooperation was to constitute a sovereign, or “Leviathan.” Paradoxically, then, people who wanted to freely contract with each other for mutual benefit should favor a powerful, coercive state.

Hobbes has a point; the ability to make credible commitments is an indispensable component of a society if citizens are to be free and responsible. If two parties cannot agree on an enforceable arrangement for mutual benefit, they are harmed by their inability to arrange to be coerced.

But Hobbes was wrong to insist that only the sovereign monarch could be the source of the contingent coercion that secures covenants. One alternative might be the use of adversarial contests to determine which “team” of political actors will run the state monopoly. North, Wallis, and Weingast (2007) claimed that the abuse of coercive power can be constrained by an open access order, with free competition. The potential for incumbent state actors to do harm is limited by the threat of replacement, because the open access order is open to entry from alternative aspirants to adjudicate disputes and enforce agreements.

The question, then, is how to sustain an open access order where the institution of the state has a monopoly on the legitimate use of force. To be fair to Hobbes, he had lived through a period that was catastrophically violent and chaotic; further, he had no examples of republican governance to reason from. Further, Hobbes had no examples of the kind of emergent institutions emphasized by classical liberals such as Friedrich Hayek and Elinor Ostrom. But in the 21st century, it has become increasingly clear that concentrating all the coercive powers of contract enforcement in a monopoly state is not necessary for workable voluntary exchange and large-scale cooperation. What is required is that open access orders be maintained on many dimensions, using a particular set of institutions that allow innovation in forms of monitoring and enforcement.

The surprising conclusion of this argument is that the solution has been in our grasp for decades- in fact, for centuries. The solution is exactly the constitutional forms suggested by classical liberalism, enabled by new forms of technology such as smart contracts and block chain generation of consensus and dispute resolution.

The simplest way to think of it is that improved technology and decentralized mechanisms for organizing cooperation have for the first time made classical liberalism feasible on a broad scale. Government, as my dissertation adviser Douglass North often pointed out, was at best a way of reducing the transaction costs of achieving the gains of cooperation. But the innovations in managing transaction costs have made that old top-down form of governance obsolete.

The result is both innovation and disruption on a scale that has been seen only rarely in human history. The source of the innovation, and the disruption, is a set of rules that allow permissionless innovation.

But we no longer live in a Hobbesian world. We live in a world where the emergent institutions fostered by classical liberalism can solve the Hobbesian problem better than the state. We need to make that argument directly: the state is obsolete, because we can do better than an unaccountable Leviathan.

As Emily Chamlee-Wright has argued, “Liberalism is a set of institutions that embody a fiction: we are all each other’s dignified equals.” Why a “fiction”? As Hayek put it:

You may ask me, “What new forms will contracts and voluntary coercion take?” My answer is that I don’t know, and it’s very important that I don’t need to know. Long live classical liberalism, and the permissionless innovation in self-governance that it fosters.

Michael Munger teaches at Duke University and is Director of the interdisciplinary program in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics (PPE) at Duke University. He is a frequent guest on EconTalk.

Read more of Michael Munger’s writing at Archive.

READER COMMENTS

Mactoul

Dec 6 2021 at 11:32pm

Surely Hobbes was familiar with republican form of government. He was writing during the English Commonwealth, wasn’t he.

I am also curious about the assertion that the state has monopoly on legitimate use of violence. Surely I can use force for self-defense, I can use force to defend my family, then to defend my neighbor, and can’t I use force to defend even a stranger from some criminal.

Jon Murphy

Dec 7 2021 at 11:43am

You can only use force as a reaction to force. You cannot initiate the use of force legitimately. Only the state can initiate the use of force.* That is what is generally meant by the state having a monopoly on force.

*NB: Just because the state can legitimately initiate force does not imply that every initiation of force by the state is legitimate.

Phil H

Dec 7 2021 at 10:52am

Could you not just hint at what the argument is supposed to be, though? As a favour to readers who took the time out to look at what you wrote?

This appears to literally say: no need for government because Uber. What is the connection? What is the claim? I like a bit of blindly optimistic techno-futurism, but I like it to have a plot and be written by Iain Banks or Arthur Clarke…

Michael Munger

Dec 8 2021 at 8:37am

Phil, it’s a blog post.

And the argument is “No need for government because smart contracts, using Blockchain.”

The term “Uber” did not appear in the article. So I’m having trouble understanding what you mean by “This appears to literally say: no need for government because Uber.”

Do you and I have different understandings of the word “literally”? Uber does not even use blockchain, and I do not mention Uber. You “literally” mischaracterize the argument in a superficial way that is frankly embarrassing.

What the blog post “literally” says is that alternatives to government will be “enabled by new forms of technology such as smart contracts and block chain generation of consensus and dispute resolution.”

If you don’t know what blockchain and smart contracts are, it is possible for you to discover more information about this things. Explaining those in a blog post is a lot to ask.

Philo

Dec 7 2021 at 1:47pm

That’s a nice quotation from Hayek’s Constitution of Liberty. But, while true, it is misleading of him to write: “the only way to place them in an equal position would be to treat them differently.” Placing everyone in an equal condition would require “leveling down” to a degree both horrendous and impracticable. If we assume that personhood begins at birth, the worst-off people are those who die painful deaths shortly after birth. In theory it is possible that every person have such a life, but there could be no one to implement such a policy (and, of course, the situation itself would be horrible).

mike.a

Dec 8 2021 at 5:50am

bitcoin solves this problem perfectly, no need for a sovereign.

Capt. J Parker

Dec 8 2021 at 12:09pm

That is a breathtaking quote. So succinctly describes a the reason for a large swath of today’s political debate.

Anders

Dec 13 2021 at 4:38am

I find it fascinating how these discussions are still firmly stuck in three traditions. The first stems from Platon, echoed in Hobbes, focussing on the need for a strong state to ensure order. The second stems from Aristotle, highlighting the caution needed before deciding on collective action – echoed in Locke and reformulated repeatedly, such as in the knowledge problem of Hayek. The third, based on Rousseau, aims to combine the two tradition by positing the existence of the general will as justification for and constraint on state coercion.

Or am I missing something?

Comments are closed.