Critics of immigration often point to the fact that the post-WWII decades were a sort of golden age for American workers, with rapid growth in real wages up until about 1973. They argue that the immigration changes of the 1960s opened the floodgates, leading to much higher rates of immigration and lower wage gains for workers.

Some people argue that it’s simply a question of supply and demand—more supply of workers means lower wages. Economists often reply that more people also means more demand for goods (and hence labor) so the impact on wages is unclear. The US has lots more workers than Canada, but similar wages.

Here I’d like to set aside the demand issue, and focus on the supply of workers. Is it plausible that immigration explains slower real wage gains after 1973?

For this hypothesis to be correct, it would have to be true that growth in the number of workers accelerated after 1973. After all, if it’s “just a question of supply and demand”, then what clearly matters is not immigration per se, rather what matters is the total supply of workers. Immigration is just one input into that total supply; natural population increase is another.

Here’s a graph of total employment in the US since January 1948:

Between January 1948 and January 1973, employment grew at 1.45%/year. From January 1973 to January 2020, employment grew at 1.38%/year. So the supply of workers actually grew more slowly during the late 20th century immigration boom than during the post-WWII decades. And the slowdown for non-farm payrolls was even more dramatic, as during the earlier period there was still a lot of labor moving from farms to the cities.

To be clear, this doesn’t prove that immigration didn’t reduce wages, ceteris paribus. That would require a more sophisticated study. What is shows is that the “common sense” argument that more supply of workers obviously leads to lower wage gains doesn’t explain why wage growth slowed after 1973—some other factor must have been involved. (I suspect that a slower rate of productivity growth was the main problem, with a lot of wasteful spending on fringe benefits such as medical care being another factor.)

It is possible that immigration affected real wages in certain industries, especially the wages of less skilled workers. If so, the US might want to consider switching to an immigration policy where the productivity of immigrants more closely matches that of the existing US population. Because many illegal immigrants are low skilled, that would mean shifting our legal immigration toward higher skilled workers. My own view is that low skilled immigration is fine, but politically it’s a tough sell.

This post was motivated by a tweet that showed a stunning decline in US population growth, to a rate of barely over 0.1% in 2020-2021. This is partly due to Covid, which reduced births, increased deaths, and reduced immigration. But population growth has been slowing for decades.

Some might point to the fact that a smaller labor supply during Covid has been associated with more rapid wage gains. But it is real wages that matter most, and real wages have fallen over the past year.

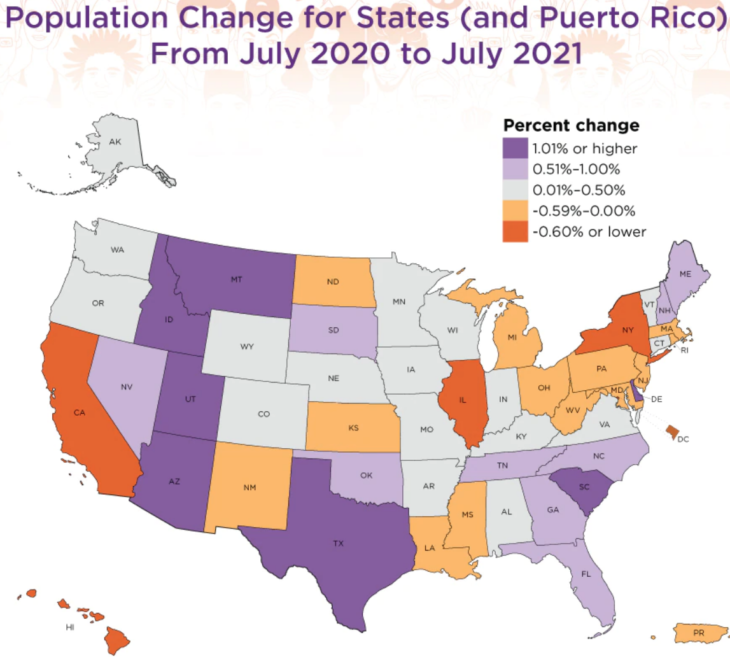

BTW, the following map shows that the Covid pandemic has led to some unusual population changes:

Some of these changes, such as rapid growth in Texas and Idaho and population decline in Illinois and West Virginia, have been going on for years. But some changes are surprising, such as the decline in population in Massachusetts and DC, and the fast growth in Montana. That might reflect people leaving dense areas for supposedly (but not really) safe low-density areas. Or it might reflect people who work from home choosing to live where they can go hiking in the mountains. (Or some of each.)

New York and California have consistently relied on international immigration to offset domestic outmigration. With the flow of foreign migrants sharply reduced by Covid, their populations declined significantly.

PS. Montana does have a slightly lower death rate from Covid than Massachusetts (but much higher than DC). But after the initial wave in the spring of 2020, Montana has been hit harder than Massachusetts. So fleeing to low-density areas doesn’t seem to make much difference. On the other hand, the difference between states may be partly behavioral, so if cautious Massachusetts migrants to Montana continue their safe practices in their new home, they might be safer after all.

PPS. Reduced immigration is a factor in the current labor shortage, as this Washington Post story illustrates:

READER COMMENTS

Kevin

Dec 21 2021 at 9:09pm

Is there any chance that more women entering the labor force since 1973 has had an impact on wages?

Scott Sumner

Dec 21 2021 at 10:28pm

Yes, that may have depressed average hourly wages.

Jose Pablo

Dec 21 2021 at 11:52pm

And yet, nowadays*, you never hear the argument that “women entering the labor force reduces “wage gains” for workers”.

Why is that (even if proven true) this is an argument against immigration but not against women incorporation to the labor force?

An interesting “suspension of belief” on the effects of an increase in the supply of workers.

* Although it used to be one of the prevalent arguments driving labor legislation until, at least, Adkins decision in 1923. Leonard’s “Illiberal Reformers” offers an interesting recount of this topic.

Jose Pablo

Dec 22 2021 at 6:18pm

One relevant question is not whether or not “women entering the workforce reduces wage gains”. The question is:

Why is the argument “immigrants entering the workforce reduces wage gains” much more prevalent than the argument “women entering the workforce reduces wage gains” (or even “native young workers entering the workforce reduces wage gains”?

After all, supporting the former but not the latter requires a model in which the effect of immigrants entering the workforce is different from the effect of women entering this same workforce.

Supporting the former but not the latter rules out, I think, most of the supply-demands arguments you can make (or at least forces you to “sophisticate” your arguments significantly).

And yet, it is very difficult to find, among people supporting the first argument, people that support (at least in public) the second argument too.

Michael Hammock

Dec 22 2021 at 10:04am

Why would it it depress average wages? Women, like immigrants, are both producers and consumers. Their entry into the labor force increases labor supply and increases labor demand. The net effect on wages should be ambiguous.

One the other hand, more people participating in labor markets means more specialization and division of labor. That should cause an increase in real wages, ceteris paribus.

Dylan

Dec 22 2021 at 1:14pm

Why would it increase demand? Those women, unlike immigrants, were already consumers in their local economy. I’m sure demand shifts to different products and services when women en masse entered the workforce, but it isn’t clear(to me) that it would increase demand overall.

Philo

Dec 22 2021 at 1:29pm

It would increase supply; therefore, it would increase demand. (Say’s Law.)

Michael Hammock

Dec 22 2021 at 3:49pm

To add to Philo’s response (which is exactly what I was getting at), think about what your argument suggests: If the entry of people into the labor force increases supply but not demand, then the entry of new, young workers should depress wages. Wages should have been falling steadily as the population grew. Does that make any sense?

Women (and immigrants and young people) who enter the labor force generate income, and with that income they purchase more goods and services than they would have purchased without that income. Those goods and services must be produced, and that increase in the demand for those goods and services increases the (derived) demand for labor to produce those goods and services.

Dylan

Dec 22 2021 at 4:16pm

I see what you are saying and I think I didn’t make my point very well. Women have always been in the labor force and producing goods and services, it’s just the type of services they have been providing and the compensation that they have been providing has changed. I can see an argument for women became more productive, doing their career along with housework, and therefore demand increased. But, if they just switched jobs from the informal to the formal sector, I don’t see overall demand increasing (even if it is more visible and easily counted).

Jon Murphy

Dec 23 2021 at 8:21am

Demand can increase for a number of reasons. One of those reasons is the increase in income of the consumers. If women moved from unpaid to paid work, then demand could increase even though the number of consumers remains the same

Scott Sumner

Dec 22 2021 at 2:08pm

It depresses average wages because women earn less than men. It doesn’t depress the wages of men, AFAIK.

Michael Hammock

Dec 22 2021 at 3:45pm

Women outside the workplace earn a wage of zero. If they earn more than zero, average wages rise. Women entering the workforce could even increase the hourly wage of men, but cause the average wage to fall if one doesn’t count the zeroes for women outside the workforce.

If we’re going to ignore those zeroes–which, granted, conventional measures do–then discussing average wages is pointless. Any entrant of any new worker into the labor force is likely to reduce average wages. I don’t think that’s what Kevin was trying to get at with his question.

Jon Murphy

Dec 23 2021 at 5:11am

Average wage measures the average of those working for a wage in the labor force. Individuals not in the labor force (working from home, retired, in school, etc) are not included in the calculation. So, a woman (or a man) outside of the workplace earning no wage does not reduce average wage

Michael Hammock

Dec 23 2021 at 1:09pm

Yes, that’s exactly what I said in my post, and also why “women entering the workforce reduce the average wage” is not particularly interesting or useful. If we’re not going to count the zeroes, then the decline of the average wage doesn’t tell us anything useful about anyone’s well-being. The average wage can decline even when everyone’s wage is going up!

Andrew_FL

Dec 22 2021 at 12:57am

Why do many “Economists” reply to this argument with such a mistaken point, which goes against Mill’s fourth fundamental proposition concerning capital, that the demand for commodities is not the demand for labor, “the best test of a sound economist”? Why do “Economists” not reply, instead, with a sound argument, that those who believe immigration reduces wages are mistaken because they have fallen for the common fallacy of the “lump” of labor? There is not one single market for labor in which all “workers” compete to supply hours and effort. There are many markets for labor, as labor is a heterogeneous class of goods, which are not in general substitutes.

Matthias

Dec 22 2021 at 3:51am

You are right about labour in general being heterogeneous.

Unskilled labour however can often be treated as substitutable.

Jon Murphy

Dec 23 2021 at 10:04am

Be careful here; the point about increased number of consumers increases demand for goods and services, which then also increases demand for labor, is not the same point Mill is making. Mill is arguing against the “general glut” hypothesis, that decreased spending by one group can be offset by increased spending by another.

Fred

Dec 22 2021 at 10:55am

I wish that there was a better way to display the US population shifts than a geographic map. Some of the states with large areas have low population, and some highly populated states have a small footprint. The changes in North Dakota and adjacent Montana probably reflect about seven people moving from Bismarck to Bozeman but are a large part of the map. US population changes are important, and we need to have a good way to represent them.

Thomas Lee Hutcheson

Dec 22 2021 at 11:30am

I sort of think that very few people got worried about slow gains in wages and mistakenly hit on immigration and free trade as the reasons.

Henri Hein

Dec 22 2021 at 1:04pm

That’s a great point. I have an additional question about the case against immigration. Assume a wave of immigration. How would we even measure that the wages of natives went down during or after? Average wages in general may have gone down, but that includes the wages of the new immigrants. We don’t know if the wages of the natives went down, or if the immigrants took lower-paying jobs that would have been unfulfilled absent immigration.

Thomas Lee Hutcheson

Dec 23 2021 at 8:17am

This year’s Nobel prize for economics went to people for developing the kinds of methods needed to answer that question.

Jon Murphy

Dec 23 2021 at 10:05am

There are lots of empirical ways to answer that question. A simple way would be to look at the wages of natives (and only natives) before and after the wave.

Henri Hein

Dec 23 2021 at 1:04pm

OK. It doesn’t sound simple to me, but maybe it’s just because I wouldn’t know how to do it. You could do it with surveying, I suppose, but I’m not a big fan of survey data.

Ken P

Dec 23 2021 at 1:41am

I’m very skeptical of that theory. More likely is that people left areas with high Covid restrictions for areas that maintained more freedom.

It’s a pretty big change to pull up your roots and move across country, so I’m sure there is a multitude of contributing factors. It’s an even bigger move to move to another country and we really should be more welcoming to people who make that choice and chose our country.

Lizard Man

Dec 23 2021 at 2:33pm

When urban land (housing) is the limiting factor of production, won’t population growth be very likely to lower wages via increases in rent and house prices? Isn’t that the reason why California has the highest poverty rate in the nation (PPP adjusted) when it also has the highest nominal wages?

Comments are closed.