Most people view legal market activities, such as buying goods and services, as being in a very different category from illegal activities where violators face penalties. But the distinction between these two categories is not always clear.

My wife and I recent stayed just outside Pucón, Chile. We drove into town for dinner and parked in what looked like a legal spot on the street. (I don’t speak Spanish, so I’m not certain.) After dinner, we found a parking ticket on our windshield.

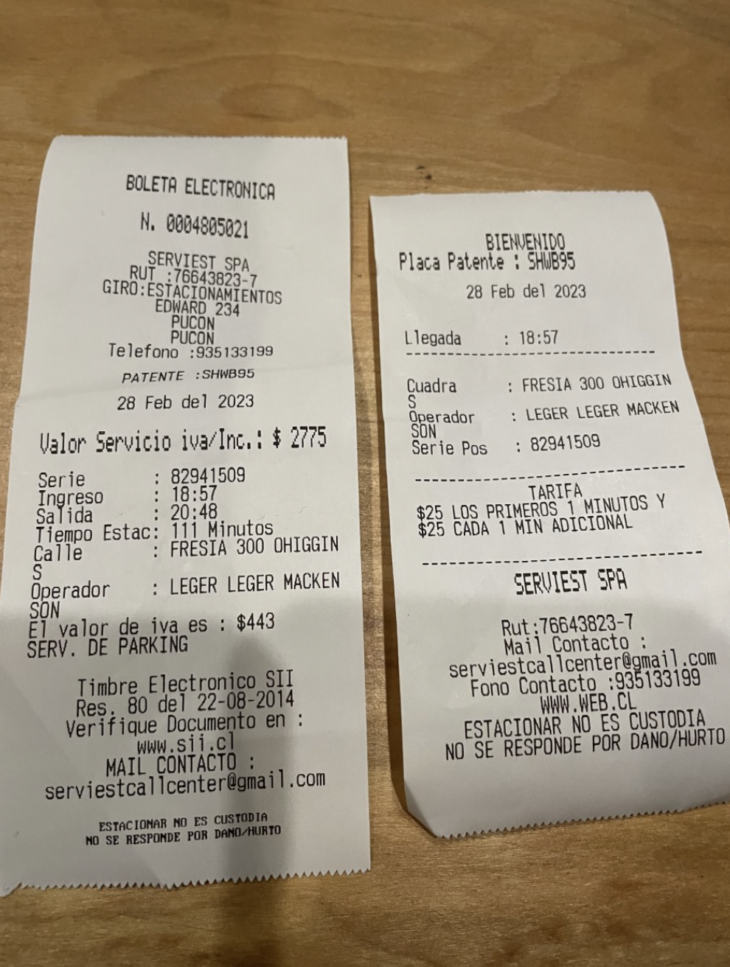

At first, I thought I’d wait and pay the ticket when I returned the rental car. But I noticed that the fine was 25 pesos per minute (about 3 cents per minute.) So I looked for one of the numerous men that were writing the tickets. It turns out I was able to pay the modest fine on the spot, and get a receipt (shown below.). The next couple of nights we again got a parking ticket, and immediately paid it in a similar fashion.

This experience got me thinking about the difference between ordinary market activity—such as parking in a garage and paying a fee of X dollars per minute on leaving, and parking in Pucón and paying a fine of X pesos per minute when leaving Pucón. What is the essential difference between a crime and an ordinary market transaction?

[BTW, the post title is a reference to the old joke about a sign that says “Fine for Parking”. Does that sign mean parking is illegal, or that it’s perfectly fine to park your car in that spot? That’s what I wondered about Pucón.]

Society often scolds people for committing crimes. But why is one set of activities (crimes) viewed as wrong, while another set (market transactions) is viewed as acceptable? If the fine accurately reflects the social cost of your activity, why should we feel guilt about engaging in a crime and paying the price?

I suspect that our feeling of outrage regarding some lawbreaking reflects a (correct) intuition that our criminal justice system frequently does not lead to efficient outcomes. First consider an example of a law violation that is “efficient”:

Suppose I value parking illegally in a specific place at $15. Also assume that society views the violation as imposing a social cost of $10. In that case, my breaking the law might be efficient. The government might assume that there is a 50% chance I will get caught for this infraction, and impose a $20 fine for illegal parking. In that case the expected penalty is (.50)*$20 = $10. If I value the parking spot at $15, I’ll take the risk.

Now consider a case where someone mugs a pedestrian and steals their wallet. Common sense suggests that this is generally not an efficient outcome for society, even if the criminal is poorer than the victim. Crime imposes all sort of other costs. People devote resources to avoiding crime. A mugging is physically and psychologically traumatic. Because muggers are often poor, financial penalties must often be accompanied by prison. And while paying a $20 parking ticket merely transfers funds from one person to the general public, prison is an expensive burden on taxpayers. A deadweight loss.

To summarize, a parking violation is more akin to an ordinary transaction than it is to a typical felony. That’s one of the reasons why we don’t feel the same sense of outrage toward a violator of parking rules as we feel for someone whose actions impose serious negative welfare effects on society.

Parking violations feel a bit different from normal market transactions because the penalty is stochastic. We might pay no penalty at all, or we might pay more than we expected. After three nights in Pucón, I discovered that the tickets were not random. Each time, a ticket was put on my windshield almost immediately after parking. I came to see the little town of Pucon as being like one giant parking garage. That removed the stress of thinking about whether I was likely to “get a ticket” or not. I began viewing it as a normal market transaction.

PS. I suspect that the way we think about lawbreaking and penalties has an impact on how we choose to address problems such as externalities. Economists tend to favor imposing a “pollution tax” set equal to the size of the external cost from pollution. Some environmentalists prefer a more rigid regulatory approach, and are skeptical of ideas such as “paying to pollute” and the “optimal quantity of pollution”.

READER COMMENTS

Thomas Lee Hutcheson

Mar 2 2023 at 8:43pm

Ideally (transactions costs get in the way) streets and roads (parking or motion) would be paid for by users. (Now there might be some spots, close to corners or in front of driveways where it really should be prohibited with a fine for “violation”) The charge for use would depend on demand at that time and place and would include a charge for the externality of being part of congestion.

Thomas Lee Hutcheson

Mar 2 2023 at 8:46pm

And “No parking, both sides of the street” is otiose as one can only park on one side of the street at a time, never both. 🙂

Scott Sumner

Mar 3 2023 at 4:49pm

The comedian Steven Wright has a similar example involving one way streets. “But officer, I was only going one way.”

nobody.really

Mar 5 2023 at 3:09am

I see nothing ambiguous about “Fine for parking.” Clearly it means that the authorities sanction parking there. 🙂

J Mann

Mar 6 2023 at 2:44pm

Love it.

Felipe

Mar 3 2023 at 12:36am

That’s not a parking.ticket. that’s a parking invoice, so you were never doing anything “wrong” or “illegal”.

That is a valid electronic invoice (boleta electrónica), authorised by the SII (our IRS), charging you 25 pesos per minute, VAT (IVA) included. You were never “fined”. We just are less effective than you at charging for parking. Instead of having park meters we have small armies of men charging you when you leave.

Good thing you didn’t feel bad about it 🙂

PS: SPA in Serviest SPA means stock -based-partnership, much like you would put Inc or Ltd in the US.

Felipe

Mar 3 2023 at 12:51am

PPS: I hope you are having a great time in Chile. If you are doing anything more “public” in Santiago please publicize it here, I’d be happy to attend if possible

Scott Sumner

Mar 3 2023 at 5:48am

Thanks for that information–very helpful.

“That’s not a parking.ticket. that’s a parking invoice”

Yes, but what’s the difference? Invoice, ticket, they are just words.

BTW, I would not have felt guilty about either a ticket or an invoice–it’s all the same to me.

Thanks for the invitation but this is just a vacation. I’m not planning any talks.

Brandon

Mar 6 2023 at 10:45am

Ah, thanks Felipe, that also explains the gmail.com address!

robc

Mar 3 2023 at 12:03pm

I was in Italy (ugh, 32 years ago) and running late for a train, I didnt have time to buy a ticket so just hopped on and paid the “fine” when they came around checking tickets. I think it was 3x the normal ticket price.

Which was totally worth it to me, because I didnt want to wait for the next train.

Scott Sumner

Mar 3 2023 at 4:48pm

Good example.

MarkW

Mar 6 2023 at 8:00am

We did that in Italy once too. The train was leaving, so we just jumped on and figured we’d pay on the train or at the next stop. But official came around and the fine really was that-huge. With my minimal Italian, I was able to get it down to just one fine for the four of us, but it was still several times the cost of 4 tickets. In retrospect, I assume the huge fines are there to keep locals from cheating and also to fleece the occasional unsuspecting tourists.

robc

Mar 6 2023 at 1:41pm

I remember it being large enough that I didnt do it again, but not so large that it wasn’t worth it.

MarkW

Mar 7 2023 at 9:59am

I seem to remember an initial fine of 50 Euros a person that was eventually cut to one fine of 50. And this was on a short trip on a regional train.

Arqiduka

Mar 5 2023 at 4:11am

Obligatory joke,

Foreign gentleman is sports car was doing 100 in 50 area, and was stopped by the police, who present him with the ticket.

“Just 100 dollars, huh?”

“That should teach you!”

Gentleman hands over 1000 dollars in bills.

“Feel like doing a few more laps, keep the change boys”

Jens

Mar 5 2023 at 4:26am

A difference on the individual level could be further legal consequences. The mere payment of a bill or a fine are similar transactions from an economic point of view. However, the invoice or fine is paid on the basis of different legal facts, to which other legal consequences beyond the mere payment may also be attached.

I have no knowledge of the Chilean legal framework. But real parking violations in other jurisdictions may also result in costly and ardous towing or direct liability for random consequences (obstruction of law enforcement, emergency services, fire departments). If the parked vehicle is involved in an accident, it may also matter whether you were allowed to park there or not.

On the other hand, implied or explicitly entered legal relationships (that normally result in having to pay an invoice) may also result in the contracting parties having secondary contractual obligations that go beyond the mere exchange of primary obligations. For example, a private parking lot operator might be obligated to inform parkers of obvious dangers from thieves or leaks of operating fluids; or he might be obligated to prevent drunk drivers from parking in a manner that might be dangerous to other parkers. In certain legal relationships (doctor/patient, lawyer/client, prison/prisoner) these collateral duties can even be very extensive.

So there are very different imponderables and risks arising from the different legal frameworks from an individual perspective. Now, one could say that it all depends very much on the specific legal system, whether that makes sense in each case and is welcome or not. And that is exactly my point.

MarkW

Mar 6 2023 at 8:03am

Another version of ‘Fine for Parking’ is ‘No Parking Regulations Enforced’. Somebody actually had a photo of a sign with that one on it.

Floccina

Mar 7 2023 at 3:29pm

Reminds me that, my father lived near a beach. and had a 4 car wide 1 car depth driveway and people would frequently park in his spaces and he tried various no parking signs but none worked, so he put up a sigh that said “parking $30” and no one ever parked there again.

Floccina

Mar 7 2023 at 3:49pm

On more thing:

Why don’t countries readjust their money more often? It seems inefficient to have your unit equal to just $0.0012.

bill

Mar 8 2023 at 3:37pm

It seems every sign around here says something like:

2 hour parking, 8am to 8pm, except Sunday.

I always think, “does that mean no parking at all on Sunday, or that the 2 hour max doesn’t apply on Sunday? It seems they mean the latter, but it still makes me nervous.

Comments are closed.