The Economist has a couple articles on the rise in economic nationalism, which make some important points:

For many in Washington—both Democrats and Republicans—this new [protectionist] approach is common sense. It is, they believe, the only way that America can protect its industrial base, fend off the challenge from a rising China and reorient the economy towards greener growth. But for America’s allies, from Europe to Asia, it is a startling shift. A country that they had counted on as the stalwart of an open-trading world is instead taking a big step towards protectionism. They, in turn, must decide whether to fight money with money, boosting their subsidies to counter America’s. If the result is a global subsidy race, the downsides could include a fractured international trading system, higher costs for consumers, more hurdles to innovation and new threats to political co-operation.

The first big crack in America’s commitment to free trade came when Donald Trump levied tariffs on products from around the world. In some ways, though, it is this second crack—the present ratcheting up of subsidies—that hurts more. “Free trade is dead” is the blunt assessment of a senior Asian diplomat in Washington. “It’s basic game theory. When one side breaks the rules, others soon break the rules, too. If you stand still, you will lose the most.”

European officials are outraged:

The angrier reaction in Europe is partly because of its weak position. . . . There is anecdotal evidence that Europe is already losing investment. Northvolt, a Swedish manufacturer, is reviewing its plan for a factory in Germany in favour of its existing American operations. Others will follow.

In theory, our allies could bring a case to the WTO, except that the US has effectively destroyed that organization:

The WTO’s prohibition against subsidies involving local-content requirements is clear. Yet so far there is little appetite for such a challenge. If America were to lose, it could appeal against the ruling, which would in effect bring the case to an end since the WTO no longer has a viable appellate body (thanks to America’s decision to block appointments).

On the other hand, the “senior Asian diplomat” who said, “If you stand still, you will lose the most” was wrong; indeed just the opposite is true:

There is an economic rationale for staying on the sidelines. When America pays for technologies at great cost to its taxpayers, these technologies should, in time, become cheaper for everyone. However much America throws at its companies, it cannot have a comparative advantage in all products. Some officials in Asia cling to the hope that their governments and those in Europe will exercise restraint. “That way all non-Americans could have a level playing field with each other,” says a Japanese official.

But the voices calling for more subsidies seem to be prevailing.

Most politicians don’t understand the economics of subsidies. It’s not a question of subsidies helping one country and hurting another; all countries suffer.

Here’s what politicians don’t understand. It is not possible for governments to subsidize “industry” as a whole. All they can do is boost one industry at the expense of another. If the US subsidizes industries A, B and C, then we implicitly penalize industries D, E, and F. Two hundred years ago, David Ricardo developed the concept of comparative advantage, which explains why helping one set of industries effectively hurts the remaining industries. Back in the 1990s, Paul Krugman pointed out that for many people, included even high-level policymakers, “Ricardo’s Difficult Idea” is hard to grasp. Policymakers view the world in partial equilibrium terms when they need to look at things from a general equilibrium perspective.

Every time we put a tariff on steel or aluminum imports, we give a cost advantage to Asian and European firms that use steel and aluminum, such as carmakers. Every time we subsidize US chipmaking, we give a boost to Asian and European firms that do not make chips.

Unfortunately, it’s not a zero sum game—industrial policies are negative sum. In another article, the Economist points out that these subsidies reallocate global production in a highly inefficient fashion:

By our calculation, duplicating the world’s existing stock of investments in semiconductors, clean energy and batteries would cost between 3.2% and 4.8% of global GDP. . . . Countries like China and Russia do present a profound threat to the current global order. Russia’s curbing of gas exports to Europe in response to European support for Ukraine highlights the risks of relying on such places for crucial imports. The urge among Western democracies to hobble adversaries economically to diminish such dangers is understandable. But it will have huge costs. What is more, the economic policies being adopted in the name of national security and competitiveness are so sweeping and clumsy that they are hurting allies as much as enemies. The zero-sum mindset may or may not succeed in making the world safer for democracy. But it will certainly make the world poorer. [Emphasis added]

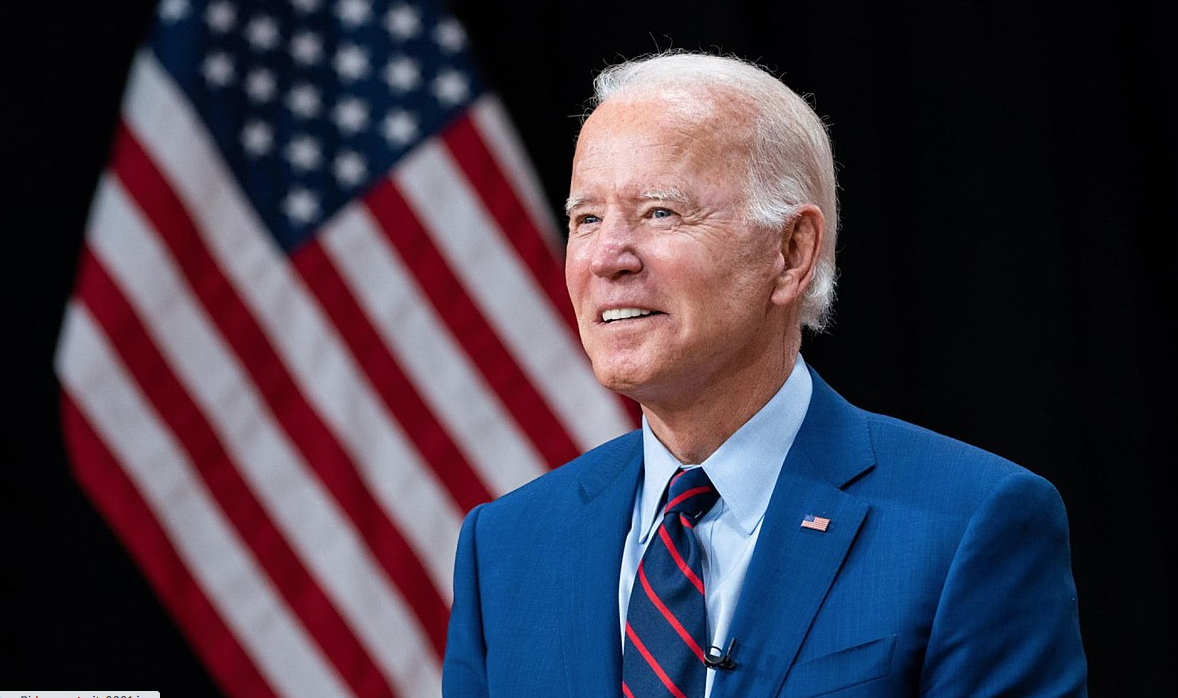

I give credit to Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen. If I had to sit in a room and listen to the economically illiterate views espoused by President Biden’s more nationalistic policy advisors, I would lose my cool. I don’t know how she puts up with it.

PS. You might say to yourself, “Sure the policies have some problems, but they can be fixed.” Nope. Too late:

President Biden suggests America “never intended to exclude folks who were co-operating with us”. Practically, though, it is not easy to recraft the rules. Legislation was written precisely, specifying amounts, timelines and conditions. Congress would need to pass formal amendments—a tall order at the best of times and inconceivable when the House of Representatives is dysfunctional.

READER COMMENTS

Jon Murphy

Feb 9 2023 at 7:53pm

Because she’s bought into it

Scott Sumner

Feb 10 2023 at 5:29am

I doubt it. Are Treasury Secretaries free to criticize their boss’s policies?

Jon Murphy

Feb 10 2023 at 10:20am

They ought to be. But are they? Probably not; I imagine a lot of pressure to sell the party line publically (in fact, I have an offer to be an economic advisor, but I am weighing it against whether I want to be a political mouthpiece).

Whether she has privately bought into their economic fallicies, the fact she publically has bought into it is dangerous, in my mind.

Mark Z

Feb 10 2023 at 5:56pm

Are they required to actively go out of their way to agree with them? She has also encouraged Europe to increase its subsidies of green technologies in response to US subsidies. She doesn’t even seem to view it as a prisoner’s dilemma type situation, but rather as ideal for every country to subsidize its domestic industries (I suppose because she thinks markets are under-allocating resources to certain industries). I see little evidence Yellen is the free-trader you imagine her to be.

ssumner

Feb 11 2023 at 7:58am

So you are saying that the sudden change in her views on protectionism just happened to occur at precisely the moment when keeping her job required her to espouse protectionist views? That’s quite a coincidence!

https://reason.com/2021/02/12/janet-yellen-knows-globalization-has-been-beneficial-why-is-she-suddenly-talking-like-trump/

And then how do you explain this:

https://www.reuters.com/markets/us/yellen-confirms-she-is-pressing-biden-some-china-tariff-reductions-2022-05-18/

David S

Feb 10 2023 at 4:10am

Immigration and trade policy continue to be my biggest disappointments with the Biden administration. It’s like Trump never left office. More accurately, I should direct my disappointment at the general mass of voters who seem to have a racist/nationalist mindset that elected officials pander to. This attitude is inconsistent with the purchasing habits of most people; when we load up our shopping carts we rarely check country of origin. The massive benefits to buyers and sellers of having a global marketplace are momentarily forgotten when some idiot starts shouting “Buy American!”

Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised by this ignorance. Mercantilism and violent conquest tended to dominate historical interactions between nation states.

nobody.really

Feb 10 2023 at 8:53am

Here you put your finger on the (or, at least, a major) issue: Humans seem prone to appeals for unwarranted types of group cohesion. Some (Hayek, for one) argue that the human propensity to groupishness derives from humans evolving in the context of families and tribes. Individuals living in families and tribes that did not band together in the face of adversity—including conflict with more cohesive families and tribes—may have had a greater chance of Darwinian elimination. Groupishness proved to be adaptive.

So today we feel “disappointment”—meaning that we learned a model of human behavior that failed to account for this groupish dynamic, we have built optimization theories based on our incomplete model, and now discover that events fail to conform to predictions. But do we feel frustration that the facts fail to conform to our model—or that we learned a model that inadequately reflects the facts?

Moreover, what to do? Maybe we can change the facts by bemoaning groupishness. Or maybe, as a second-best solution, we need to find the least pernicious form of groupishness and direct people’s energies in that direction. And in service of this second strategy, I humbly nominate—nationalism. If people must feel a desire to recognize in- and out-groups, then learning to love those who are proximate and distrust those who are remote seems to have greater advantages than the alternative.

Jose Pablo

Feb 10 2023 at 3:34pm

But do we feel frustration that the facts fail to conform to our model—or that we learned a model that inadequately reflects the facts?

I don’t see where the “conforming to our model” problem is coming from.

We “know”:

‘* Humans are groupish

‘* This human tendency makes us poorer

Both can be true at the same time. Groupishness is not helping us any longer (it has not been helping us for quite a long time … quite the contrary actually).

Unfortunately we cannot rely any longer on Darwinian elimination to correct the fact that human groupishness is hindering our economic progress. And this is apart from being extremely anti-aesthetic and morally repugnant in many of its manifestations (nationalism for instance).

Jose Pablo

Feb 10 2023 at 8:55pm

the least pernicious form of groupishness

Actually the “least pernicious form of groupishness” should include supporting the well-being of the other individuals of your group.

Since international free trade is “made” by the free decisions of these individuals, how is it possible to increase their well-being by constraining their ability to enter into this free transactions?

You need to enter into the “constrains are freedom” way of thinking to actually believe that limiting free trade helps the fellow individuals in your group.

“Nationalism” understood as “helping your fellow citizens to thrive” should enthusiastically support free trade.

Under this definition Jon and Scott seem to be the “champions of nationalism” on this chat. Others seem more inclined to support the impoverishment of their “group”.

TMC

Feb 10 2023 at 9:47am

“racist/nationalist mindset”

This doesn’t help your argument. Given that most of us commenting are in the US, and the makeup of the US population, nationalist would be the opposite of racist.

Scott Sumner

Feb 10 2023 at 4:21pm

In fairness, on legal immigration things have gotten somewhat better.

john hare

Feb 10 2023 at 4:17am

It seems to me that the base problem is that so many see life and trade as a zero sum game. Life and trade is an increasing sum game. Getting the public and voters to grasp this should solve some of these issues.

nobody.really

Feb 10 2023 at 8:15am

Should this perhaps read “Protectionism is a negative sum game”?

It is not clear to me that the world before the rise of nationalism was so much better.

Jon Murphy

Feb 10 2023 at 12:58pm

I disagree. I think the evidence is fairly clear. When we see nationalism take root, periods of war and strife tend to follow (eg: World War 1 and 2, the Italian Unification, Napoleonic Wars, etc). In periods where liberalism thrives, we tend to see more peaceful periods.

TMC

Feb 10 2023 at 4:16pm

When hasn’t nationalism been the norm? I can’t think of any time where most citizens of a country wouldn’t prefer their own country’s interest to another’s. Too much is bad of course, just like too much water is bad for you. We don’t disparage water though for its abuse.

Next thing you’ll tell me it’s bad to root for my high school over its rival.

Jose Pablo

Feb 10 2023 at 8:42pm

it’s bad to root for my high school over its rival.

The point is that, in this case, “rooting” for your high school/country is rooting for international free trade. Which makes the individual citizens of your country better off.

If your definition of “nationalism” is wanting your fellow citizens well-being then rooting for free trade is what you should be doing.

The “negative sum game” Scott is referring to, would be equivalent to hugging your high school team players so tight (out of pure “high school nationalism”) that you injure them before the game. So yes, this rooting would be definitely bad.

Jon Murphy

Feb 11 2023 at 11:22am

That’s not nationalism. Nationalism is not preferring your nation over another, but also believing your nation is superior or should be advanced at the expense of other nations.

For example, preferring your nation would be like saying “I support free trade because it makes Americans better off”

Nationalism is “I oppose free trade because China is made better off”

TMC

Feb 11 2023 at 4:15pm

nobody got it right “Should this perhaps read “Protectionism is a negative sum game”?”

Nationalism can be negative, but does not have to be. Very much like everything else. It’s protectionism that you find fault with, so why muddy the argument with nationalism when that’s not the issue? Seems like those who go on about nationalism usually need to make up their own boogieman definition to attack it.

I consider myself to be, to a large degree, globalist, but I see how that can be used for evil as well. The greatest human tragedies have been in communist China, which is nationalist, and the Nazi/Soviets who are globalists. Either and every ideology can be used for evil, so lets just attack the evil. It’s more persuasive.

nobody.really

Feb 10 2023 at 4:19pm

I suspect we need more exacting definitions. I struggle to think of a period with liberalism but without nationalism–since, if anything, I’d say that liberalism and the Enlightenment pre-dated nationalism.

True, wars follow the rise of nationalism; they also coincide with and precede nationalism.

If you accept the findings of Steven Pinker’s Better Angels of Our Nature, you’d acknowledge that the share of humans facing violent deaths has DECREASED over time. If I were to draw any conclusion about the relationship between nationalism and violent death, therefore, I’d draw the opposite one from you.

Jon Murphy

Feb 10 2023 at 5:38pm

True. Nationalism cannot really start without nation-states. Generally, I see it starting about the 1700s.

True, but irrelevant. The question is whether nationalism fosters war or not.

Pinker’s point is proof of my claim. As nationalism has receded over the past 80 years or so, so has violent deaths. The rise of nationalism again here in the 2020s is incurring more violence (eg Russia, the far right and the far left).

Scott Sumner

Feb 10 2023 at 4:18pm

Protectionism is an important part of nationalism.

nobody.really

Feb 10 2023 at 4:52pm

The US has adopted varying levels of protectionist policies over time. Would you conclude that this reflected the varying degrees of nationalism embraced by the US over this time?

Reagan reduced protectionist measures embracing nationalism:

Reagan harnessed people’s desire to affirm membership to some in-group without embracing high tariffs, etc. In fairness, Reagan enjoyed the benefit of a clear enemy to rally around: Communist nations. So he could build unity by emphasizing what he was AGAINST. And all through the Reagan years, libertarians had to suck it up and endure the Republicans’ droning on about the need to sacrifice (including supporting ENORMOUS public spending) to oppose the communist menace.

I acknowledge that nationalism has drawbacks. But with the collapse of communism, the Republican Party has become untethered from any unifying vision. In the absence of other grounds for distinguishing between in- and out-groups, the GOP seems to be drifting into religio/ethno-nationalism (among other paranoid theories). So to me, nationalism is looking pretty good right now.

If only some interstellar aliens would fly by, giving us a new enemy to rally around….

ssumner

Feb 11 2023 at 8:01am

I’ve done posts on the fallacy of conflating patriotism with nationalism. Reagan was a patriot, not a nationalist.

nobody.really

Feb 11 2023 at 10:07am

Cool–substitute patriotism for nationalism.

Again, my premise is that humans are attracted to groupishness in a way that libertarianism really fails to address. One libertarian strategy has been to simply decry this tendency. I suggest an alternative: Find the least harmful way to accommodate the tendency.

So let’s re-submit all my prior comments, swapping in the term “patriotism” for “nationalism.” NOW what do you say?

TMC

Feb 10 2023 at 8:55am

I am a big supporter of free trade, if for no other reason that I don’t like anyone telling me who I can do business with, foreign or domestic. And I understand the theory why trade is efficient. That being said, NAFTA (and its replacement), one of the largest trade agreements, has been pretty well studied. These studies point to little gain for either the US or Mexico.

That’s a pretty unexpected result, but on that reoccurs in the several studies I’ve seen. I’m not sure what to make of it.

https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/naftas-economic-impact

ssumner

Feb 11 2023 at 8:06am

I would have expected modest gains, not large gains, and that’s what studies show. Almost no single policy change will produce large gains in a macro sense. Even before NAFTA, trade with Canada and Mexico involved pretty low tariffs, thus NAFTA wasn’t a game changer.

BTW, Brexit seems to have hurt the UK economy.

BS

Feb 10 2023 at 12:40pm

Conflict is a negative sum game. The way politicians and policy wonks look at things, economic affairs are just one of the instruments of national power in the DIME (diplomacy, informational, military, economic) toolbox. They don’t look at economics as just one thing in it’s own lane.

Grand Rapids Mike

Feb 10 2023 at 2:58pm

One of the great benefits of free trade is that China sent its balloon to spy on the US military installations with US made parts. Not only that China can invade Taiwan with material made in America.

Jose Pablo

Feb 10 2023 at 3:50pm

Yes. That and the fact that the US invaded Iraq using gas coming from Iraqi oil wells.

And that the US caused hundreds of thousands of deaths in Japan in a couple of mornings, using the splitting of the uranium atom first developed in Berlin.

Wonderful, isn’t it?

Which percentage of US made parts exported to China do you think are used in spy balloons or the (hypothetical) invasion of Taiwan?.

My guess: far less than the percentage of God’s words used to kill other human beings.

Grand Rapids Mike

Feb 10 2023 at 8:22pm

So glad so hear from you. Your cogent comments are precious.

Scott Sumner

Feb 10 2023 at 4:20pm

Why is it a problem if China spies on our military installations? Are we hiding something important?

nobody.really

Feb 10 2023 at 5:13pm

Ah, military secrets…

Stripes (1981)

Monte

Feb 11 2023 at 12:17am

Right. Why not just grant a delegation of the CPC security clearances and arrange for tour of all of our military installations? That’s a helluva lot more diplomatic than shooting down one of their weather balloons.

ssumner

Feb 11 2023 at 8:10am

I assure you that if there’s ever a war between the US and China, its outcome will not hinge on whether a Chinese delegation toured our military bases!

Monte

Feb 11 2023 at 2:18pm

Oh yes sir, that’s true enough. I would just question the wisdom of allowing our enemy to blatantly gather intelligence on our military installations without repercussion, not that this would give them any type of strategic advantage. You’ll excuse me if I think your blanket statement of having no problem with them spying on us sounds a bit 5th column.

But…what the hell. If, as Jose Pablo suggests, the U.S. is every bit as evil as communist China, the absolute best outcome for the rest of the world is our MAD.

Jose Pablo

Feb 11 2023 at 8:46am

Yes. And it is very unfair since the US is always refraining from spying the Chinese military!, sure the US governmet don’t have any relevant secret information on the Chinese military (but, of course, our spying is good and theirs is bad, you know?)

The problem of the balloon is not the spying thing (what I expect to be widespread in both sides), the “problem” is the clumsiness of the whole scheeme.

It is almost like it was always arranged as a provocation. Although, when the government is involved, you can never rule out pure incompetence as the most likely explanation.

Mark Z

Feb 10 2023 at 6:23pm

“What is more, the economic policies being adopted in the name of national security and competitiveness are so sweeping and clumsy that they are hurting allies as much as enemies.”

A practical limitation of technocratic protectionism is that voters care so little about he nuances of public policy they’ll as soon reward the politician with a broad, clumsy policy as the one with the carefully crafted one. The practical alternative to free trade probably isn’t between a carefully fine-tuned, optimized trade policy. It’s basically one blunt heuristic vs. another blunt heuristic.

Jose Pablo

Feb 10 2023 at 6:55pm

Totally unrelated.

Speaking of “clumsy” policies (politicians are bad even at wording), a very likely “world record on clumsiness”

https://www.surinenglish.com/spain/flagship-toughen-sentences-20221118095422-ntvo.html

Jorge Morales Meoqui

Feb 11 2023 at 9:18am

Dear Mr. Summer,

It would help if economists in academia started to advocate free trade more rigorously, as their current case (= theory of comparative advantage) is based on a misinterpretation of Ricardo’s famous numerical example (see here).

When adequately grasped and explained, Ricardo’s case for trade is straightforward to understand. He stated:

It is generally beneficial to import a commodity that costs less to buy than to produce locally.

Carl

Feb 11 2023 at 5:29pm

I thought the optimal strategy was fit-for-tat in this sort of game. True, the tit-for-tat strategy is to trust ( i.e. keep tariffs down) until an opponent cheats (i.e raises tariffs), then retaliate in kind. But if the opponent then makes amends (I.e unilaterally drops their tariffs against you), then you should respond in kind.

Carl

Feb 11 2023 at 5:54pm

I meant to add: We can this undo the damage we have done by one round of enlightened behavior to reset the tatting.

Comments are closed.