The Economist has an article suggesting that Fed chair Arthur Burns has an undeservedly bad reputation, and “deserves a second look”:

Richard Nixon picked Burns to run the Fed, viewing him as a friend who would do his bidding. Despite stubborn inflation, Nixon pressed Burns to cut interest rates in 1971, thinking it would help him win re-election. Sure enough, the Fed did just that. Nixon was re-elected and inflation soared, hitting double digits by 1974.

But the story is more complicated than the basic outlines suggest, and its complexity contains lessons for today’s policymakers. With the holiday season upon us—and with the Fed approaching a turning point in monetary policy—it is a fine time to reassess the legacy of the much-maligned central banker.

Start with what happened after inflation took off. The Fed jacked up interest rates from 3% in 1972 to 13% in 1974, one of its sharpest-ever doses of tightening, and enough to help tip the economy into a deep recession. Doing so took some of the heat out of price growth, with inflation settling at around 6% for the remainder of Burns’s tenure.

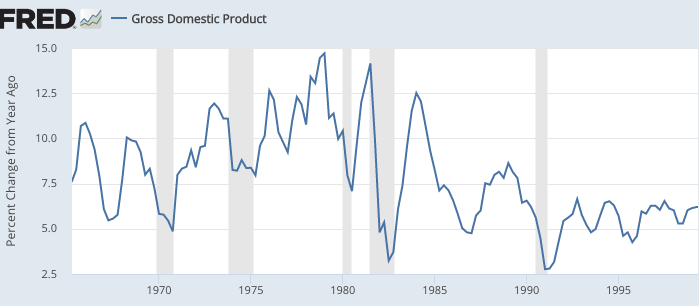

Burns was Fed chair from January 1970 to March 1978, roughly in the middle of the Great Inflation. From the first quarter of 1965 to the third quarter of 1981, NGDP growth averaged 9.6%, far too high for price stability. During the 8 years that Burns chaired the Fed, NGDP growth averaged 9.7%. And things were not getting better near the end, NGDP growth averaged 10% over his final two years, and 10.8% over the final year of his tenure. Nor did his policies have a delayed payoff after he retired due to “long and variable lags.” Inflation sped up after he left the Fed, as NGDP growth accelerated sharply in late 1978 and 1979. It is unlikely things would have been much different if he had stayed.

I also strongly object to this:

An oil shock that began in 1973 led to a near quadrupling in energy prices as well as a surge in food costs. A second oil shock in 1978, just after Burns left the Fed, kicked off another inflationary surge. Given this backdrop, how much of the inflation can truly be blamed on the Fed? A review written in 2008 by Alan Blinder and Jeremy Rudd, two economists, found that supply-side factors were decisive. They calculated that the energy and food crises accounted for more than 100% of the rise in headline inflation relative to its baseline level. The Fed could have reacted more strongly, given that inflation had already been unanchored. But Burns was not responsible for the massive shocks facing the economy.

Yes, oil shocks explain why inflation is higher one year than the next, but the Great Inflation of 1966-81 was caused by rapid NGDP growth, which was 100% due to the Fed printing too much money during a period when interest rates were not close to zero. I don’t see how this is even debatable. So why do economists continually look for revisionist explanations? Why search for alternative theories such as supply shocks, labor unions, budget deficits, etc. None of those can explain why the Fed printed to much money. If you raise NGDP at 9.6% per year for 16 years, you’ll get a lot of inflation. Over the entire period, we got roughly as much inflation as we would have had with 16 years of balanced budgets, no labor unions and no OPEC during a period of 9.6% NGDP growth. Persistently high inflation is caused by rapid NGDP growth, which is caused by monetary policy. It’s that simple.

READER COMMENTS

Jim Glass

Jan 18 2023 at 6:22pm

An oil shock that began in 1973 led to a near quadrupling in energy prices as well as a surge in food costs. A second oil shock in 1978, just after Burns left the Fed, kicked off another inflationary surge. Given this backdrop, how much of the inflation can truly be blamed on the Fed?

Germany and Japan were even more vulnerable to the oil shock than the USA as they were entirely dependent on imported oil while the USA produced a great deal of its own.

In Germany during this period the inflation rate remained low, as the Bundesbank was fully committed to stable prices due to memories of the hyperinflation.

In Japan inflation fell, as the BOJ had previously started a policy of disinflation from a ~20% level and stuck with it.

So as to the question “how much?” …. All of it?

Garrett

Jan 18 2023 at 8:02pm

So many bad theories can be quickly refuted by looking cross sectionally.

marcus nunes

Jan 18 2023 at 8:25pm

This post has nice comparison charts with Japan, Germany & UK

https://marcusnunes.substack.com/p/1970s-you-are-always-on-my-mind

TMC

Jan 19 2023 at 9:58am

“So why do economists continually look for revisionist explanations?”

Because they want to be able to print more money. The actual explanation deprives them of this.

Spencer

Jan 19 2023 at 11:00am

Yeah, I’ve been mad at Blinder ever since he wrote his new book:

A Monetary and Fiscal History of the United States, 1961-2021

It’s incontrovertible, N-gNp was too high. And that policy was due to the adoption of interest rate manipulation as the FED’s monetary transmission mechanism in 1965. The FED’s idea of monetary policy was fixated on 24 hours rather than 24 months.

Spencer

Jan 19 2023 at 11:09am

Pritchard used to read his correspondence with Burns to his money and banking classes. Pritchard was a genius.

Selgin got it right in his book “Floored”. The money supply can never be properly managed by any attempt to control the cost of credit. Interest is the price of credit; the price of money is the reciprocal of the price level.

…

Unlike Powell, you have to recognize that a bank is a bank and not an intermediary financial institution.

…

A. You have to know the difference between the supply of money & the supply of loan funds.B. know the difference between means-of-payment money & liquid assets.C. know the difference between financial intermediaries & money creating institutions.D. recognize that interest rates are the price of loan-funds, not the price of moneyE. recognize that the price of money is represented by the various price (indices) level.

Capt. J Parker

Jan 19 2023 at 1:38pm

No question that the Burns Fed gave us the great inflation. But I don’t think we should forget what was going on with fiscal policy. 1965 to 1980 saw a really big growth in federal spending.

So during Burns tenure:

Supply shocks – Expansive fiscal policy – No monetary offset – Inflation

During Powell’s tenure:

Supply shocks – Expansive fiscal policy – No monetary offset – Inflation

Monetary offset exists in theory – does it exist in reality?

Thomas Lee Hutcheson

Jan 21 2023 at 8:30am

We should distinguish between shocks (mainly supply although in principle a shold could come from demand) — changes in supply and demand that require large changes in relative prices of important sectors — and growing or shrinking deficits that (presumably) are do not much affect relative prices. The former calls for temporarily raising the the inflation target as the average price level had to rise if some prices are downwardly sticky. The latter calls for monetary offset to hold to the inflation target

Spencer

Jan 20 2023 at 12:17pm

re: “No monetary offset”

The “demand for money” shifted to the left up until 1981.

The “S-Curve” dynamic damage (sigmoid function), or the culmination in the “monetization” of time deposits by the first half of 1981, ended with the widespread introduction of new negotiable demand drafts, e.g., the effervescent “saturation value” of ATS, NOW, Super-NOW and MMDA accounts (i.e., the end of most DFI gate keeping and gov’t interest rate restrictions on bank deposits, and the transition from clerical processing to electronic processing).

Thomas Lee Hutcheson

Jan 20 2023 at 1:47pm

A supply or demand sectoral shock can explain why a Fed that is trying to optimize inflation would raise its target in response to a shock. The Fed seems to have gone far beyond this under Burns. Still bad. Worse than Bernanke-Yellen? They broke new ground with undershooting the target. Is Powell flirting with the same thing? TIPS is far below target!

Comments are closed.