In a 1930 essay titled “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren,” John Maynard Keynes predicted that in 100 years, “assuming no wars and no important increase in population,” the standard of living in “progressive countries” would be “between four and eight times as high” as it was then. His most optimistic scenario is being realized. In 2022, real GDP per capita (equivalent to income per capita) in the US has already been multiplied by 7.3, with eight years to go (see Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Income and Product Accounts, Table 7.1, revised March 30, 2023). Even if the rate of growth is only 1% per year between now and 2030, real GDP per capita will then be 7.9 times that of 1930.

Keynes also believed that with such high incomes, the economic scarcity problem of mankind would be solved and the question would be what to do with one’s free time. This part of his forecast has not held up well. Somewhat similarly, the 1960s and 1970s hippies thought they were reentering the Garden of Eden, if only capitalism could be destroyed. San Francisco’s Blue House, sung by Maxime Le Forestier, is a reminder of the dream. Keynes is more difficult to forgive.

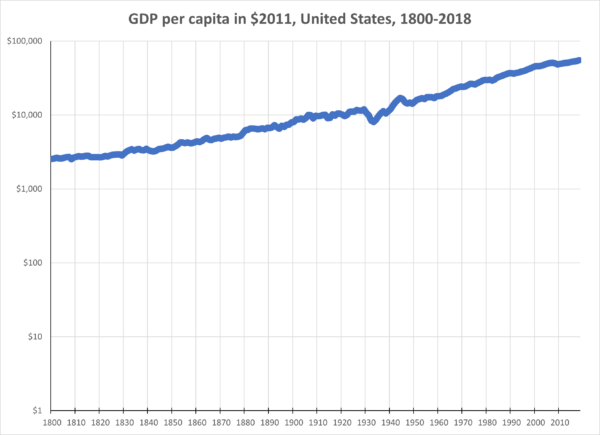

The whole 20th century has seen an incredible increase in the standard of living. In America, real GDP per capita has grown at an annual (compounded) rate of 1.8% over that century, a higher growth than in the preceding century (see the semi-log graph below, where the slope of the curve indicates the rate of growth). And that was despite two world wars, the Great Depression (and a number of smaller ones), the New Deal, and a large growth in taxes, government expenditures, welfare programs, and regulations. In the United Kingdom, Keynes’s country, population has grown by 45%. Similar economic developments happened in Western Europe and in a few capitalist countries elsewhere.

The 20th century was an intriguing century. It is sometimes difficult to avoid the impression that Mussolini was correct to expect and hope that the 20th century would be “the century of the State.” How can we explain this coexistence of economic growth and advancing state intervention? Here are a few hypotheses.

One hypothesis (the data hypothesis) is that GDP data are not reliable or decisive. It is well known that GDP per capita does not measure welfare and that it may not even provide a satisfactory measure of the general standard of living. Imagine that you are living in a Middle East oil emirate where production responds to what the princes and their courts want, as opposed to generalized consumer sovereignty. This objection raises some useful caveats but, at least in Western countries, there is clearly a strong correlation between GDP per capita and the standard of living for ordinary individuals. Any passing knowledge of history should confirm that they are incredibly wealthier than even just a century ago.

Other explanatory hypotheses are needed. Many mainstream analysts support the benign-intervention hypothesis (sometimes called “state capacity“) according to which government expenditures and taxes, the welfare state, or regulation are not as detrimental to prosperity as we thought, at least when these interventions are moderated by the rule of law and limited by constitutional constraints. My own guess is that regulation and the multiplication of criminal laws and felonies put a strong brake to prosperity and individual opportunities, much more so than the welfare state (or some implementations of it).

A related hypothesis—the counterfactual hypothesis—is that economic growth would have been more rapid without state intervention. Economists John Dawson and John Seater argued that the American GDP per capita would be more than three times its current level if federal regulation had remained at its 1949 level. Even per capita, a growth rate of 1.8% is not that fantastic. The counterfactual hypothesis has some historical support: it is certainly not the most regulated countries that spearheaded the Industrial Revolution—the United Kingdom and the Low Countries, rapidly joined by the United States. A mere counterfactual would not be sufficient to explain the strange mixture that the 20th century was, but we do have theories strongly suggesting that state dirigisme hinders prosperity, which is a natural consequence of the efforts of free individuals to improve their situations.

Another hypothesis along the same lines is that the social, economic, and political institutions that respect or promote individual liberty and free markets are very resilient once established (the resilient-freedom hypothesis). In this perspective, individual liberty is self-sustaining, at least up to a point. Economic growth continued and accelerated despite, not because of, growing government intervention. This would be reassuring. Yet, we do not know if and where a breaking point exists at which prosperity would stop or reverse like in, say, Argentina or Venezuela. It is not clear either if or how liberty and prosperity, once lost, can be regained.

Sources: Maddison Project, 2020 update, and its own sources: McCusker, John J., ‘Colonial Statistics’, Historical Statistics of the United States: Earliest Time to the Present, in S. B. Carter, S. S. Gartner, M. R. Haines et al. New York, Cambridge University Press. V-671. Sutch, R. (2006). National Income and Product. Historical Statistics of the United States: Earliest Time to the Present, in S. B. Carter, S. S. Gartner, M. R. Haines et al. New York, Cambridge University Press III-23-25. Prados de la Escosura, L. (2009). “Lost Decades? Economic Performance in Post-Independence Latin America,” Journal of Latin America Studies 41: 279–307. (Chart by P. Lemieux.)

READER COMMENTS

nobody.really

Apr 24 2023 at 1:29pm

I see two hypotheses here. One hypothesis argues that GDP fails to adequately capture the concept of welfare. A second hypothesis says that, whatever the merits of GDP for measuring welfare, per capital GDP fails to reflect the standard of living for ordinary individuals. Sitting at the bar, Sven and Ole see Elon Musk walk in. “Yippee!” Sven shouts, “The average wealth of everyone in this bar just skyrocketed!” Ole is puzzled: “That has no bearing on us.” Sven brushes it off: “Spare me your class warfare talk….”

The backwards-bending labor supply curve suggests that the ordinary individuals would substitute more leisure for work if ordinary individuals had higher incomes. And they WOULD have a higher incomes if the average individual’s income were closer to per capita GDP (for 2021, roughly $23.32 trillion GDP/331.5 million US population = roughly $70,000/person). Instead, median income was roughly half of this, or $37,500/person. So perhaps Keynes was anticipating greater income equality?

As Thomas Picketty and others have noted, income inequality has grown enormously since Reagan took office in 1980. But ironically, inequality had been falling for much of the time prior to that–and in 1930 income inequality was roughly the same as it is today. I don’t know whether Keynes had the data to know that, however.

nobody.really

Apr 24 2023 at 2:31pm

Alternatively, in 2021, average GDP was roughly $180,000/household ($23.32 trillion/130 million US households).

Real median household income was about 40% of that, or about $70,800/household.

Pierre Lemieux

Apr 24 2023 at 3:35pm

Nobody: Following up on my previous comment, here is a peek at the problems in commparing the Census Bureau’s CPS (Current Population Survey) with national account data:

In short, the CPS definition of income is not as comprehensive (or cross-checked) as what you find in the national accounts. Perhaps you can find some more recent studies that would bring us up to date on that issue?

In a more general perspective, let’s not forget that there are two kinds of inequality: one that results from the independent actions of equally free individuals (look at what singers, actors, and athletes earn!); and one that results form public choices (that is, political and bureaucratic decisions).

Pierre Lemieux

Apr 24 2023 at 3:04pm

Nobody: A certain prudence is required with these figures. Real GDP per capita was $59,995 in 2022 in dollars (see Table 7.1). This is equal to average income in the US: everything that is produced on the US territory corresponds to an equivalent income paid to some individual or corporate US resident (in wages, salaries, rents, interest, profits). The median income is a different statistics, calculated by the Census Bureau, incompatible with national accounts figures, and subject to much criticism. It is equal to $67,521 (current dollars) per household in 2020. In my populist moments, I suggest just to drive by a public high school and look at the cars in the parking lot. (They don’t belong to Musk.)

nobody.really

Apr 24 2023 at 4:35pm

As I understand it, Lemieux asks why Keynes’s prediction about the growth of wealth became true, but prediction about the growth of leisure “for ordinary individuals” did not.

I hypothesize that if we had greater income equality, we’d see people consuming more leisure. Now, I grant that securing all the best data poses challenges. Doubtless there are other factors at play, too. Keynes may have overlooked the idea that people would continue to work more because they want to consume more: Most of us live longer, and in bigger houses, than back in the 1930s, and perhaps there is more stuff to consume than Keynes ever imagined. Leisure is not the only (superior) good that we consume more of as we get richer.

Nevertheless, I’ll also stick with the inequality hypothesis. I appreciate that some people may defend the current levels of income inequality, but I don’t know how that bears of the question: Keynes hypothesized a certain level of wealth in the future, and was right. He also hypothesized how a more affluent society might invest in leisure, but was (arguably) wrong. Yet it strikes me as self-evident that the way wealth is distributed throughout a society would have some bearing on the amount of leisure consumed in that society. I doubt that anyone acquainted with the general shape of the data–specifically regarding the disparities between median and average income (and median and average wealth)–and acquainted with the functioning of the backward-bending labor supply curve would dispute my hypothesis. If anyone does, please say so; I’d like to hear your thoughts.

Jose Pablo

Apr 24 2023 at 5:09pm

Keynes can still be right on the “leisure prediction”. Measuring “leisure” has the same problem as measuring a prince index, how do you take into account increases in the “quality” of the product?

I am talking just from anecdotal evidence, but it seems to me that the quality of “leisure” has increased veryyyyy significantly in my family since my great-grandfather’s time.

He used to attend a service in the church on his non-working days or, if he could avoid my great-grandmother (not an easy task by any means), travelling (sometimes on foot) to the neighboring village to attend some dancing (A dancing blessed by the local priest, so not really that fun) and drink a couple of shots (mostly undrinkable by today’s standards)

I will fly to Bali for a scuba diving fortnight this summer. Maybe I work the same hours than my grandfather, but I very much doubt we have the same “leisure”

Pierre Lemieux

Apr 24 2023 at 5:22pm

José: Interesting point. Except for the convertible part, it’s much less trouble and more fun (for most people) to have a long leisure trip in a Kia Rio than in a Ford T.

Jose Pablo

Apr 24 2023 at 5:28pm

Trying to get a rough index of “leisure quality” here:

I think I would prefer 30 minutes of leisure spent watching Netflix today than 5 or 6 hours reading the Reader’s Digest Condensed books that were in my family house in the 50s

That’s roughly an index of 10-12 times. So yes, Keynes was totally right! we do enjoy a huge amount of leisure today!

nobody.really

Apr 24 2023 at 6:17pm

Yeah, I want to acknowledge MarkW and Jose Pablo for flagging the idea that we DO consume more leisure than in 1930. Cars were still pretty new, and the US Rural Electrification Administration didn’t get started until 1935. So large chunks of rural America–and that was MOST of America–worked their jobs, and then went home to shovel coal into their furnaces and pump water into their cisterns and wash clothes and hang laundry and wash dishes and sweep floors and cover the ice with straw and feed the horse and repair the roof and and and…. On top of this, you’d add the work of maintaining social relationships in an era that predated telecommunications, and the time spent in transit in order to accomplish anything that required the participation of someone outside your household.

(People grumble about how regulation burdens business, with some cause. Yet today I could live in Timbuktu, file articles of incorporation in Delaware, set up a web page offering corporate drafting services, receive orders and payments, and transmit documents–all without leaving my chair. So on balance, I have to suspect that doing business has almost never been easier–and certainly easier than in 1930.)

I don’t want to deny that some people do spend 16 hrs/day on their paid employment–and today’s rich (unlike the landed gentry) are more likely to put in very long hours. But I’d ask us to acknowledge that someone has to do all the domestic chores that makes such a lifestyle possible. Today it’s easier to overlook those chores because so many of them are automated. Fewer people have been able to overlook those chores in 1930, because real human being in your household were performing them.

Anyway, maybe Keynes’s thesis was stronger than I (and Lemieux) had initially acknowledged.

Jose Pablo

Apr 24 2023 at 4:54pm

Sitting at the bar, Sven and Ole see Elon Musk walk in. “Yippee!” Sven shouts, “The average wealth of everyone in this bar just skyrocketed!” Ole is puzzled: “That has no bearing on us.” Sven brushes it off: “Spare me your class warfare talk….”

Well, the impact of Mr Musk (Elon be praised!) on Sven and Ole wellbeing, is significant. In fact it has a lot of bearing on them (and more to come) … the impact just happened before they entered the bar (as “impacts” normally happen).

Pierre Lemieux

Apr 24 2023 at 5:13pm

José: Ole might be one of the mass-men the other José (Ortega y Gasset) wrote about. The mass-man just inherited civilization i.e. prosperity, and thinks that it will always be there whatever other mass-men like him do destroy liberal institutions. Ole believes that his income “is the spontaneous fruit of an Edenic tree,” to quote Ortega. More on this in my forthcoming review of Ortega’s The Revolt of the Masses in the Summer issue of Regulation.

Jon Murphy

Apr 24 2023 at 2:17pm

One thing I think worth pointing out is the caveat Keynes imposed: “no important increase in population.” Keynes was a Malthusian who believed higher population reduces economic growth. The US population has more than doubled since Keynes made his prediction and it is still coming true. Keynes, it turns out, was right but for the wrong reasons.

Mark Brady

Apr 24 2023 at 6:27pm

“Keynes was a Malthusian who believed higher population reduces economic growth.”

That statement does not adequately summarize Keynes’s take on Malthus. Nor does it do justice to Keynes. If anyone else is interested in pursuing this further, I recommend that they read Duncan Kelly’s “Malthusian moments in the work of John Maynard Keynes,” Historical Journal 63, 1 (2020): 127-158.

Jon Murphy

Apr 25 2023 at 6:31am

Obviously, I disagree (otherwise I wouldn’t have said it). I touch on Keynes’s thoughts on population in my article “The Ambiguity of Superiority and Authority: An Analysis of the Keynes-Tinbergen Debate” (2022) in The Erasmus Journal for Philosophy and Economics 15(2). Phil Magness and James Harrington discuss it in greater detail in their 2020 article “John Maynard Keynes, H.G. Wells, and a Problematic Utopia” in the History of Political Economy 52(2). Phil and Sean Hernandez also discuss it at legnth in their 2017 article “The Economic Eugenicism of John Maynard Keynes” in the Journal of Markets and Morality 20(1).

Jon Murphy

Apr 25 2023 at 6:32am

Oh, and John Toye’s 2000 book Keynes on Population has good details, too.

MarkW

Apr 24 2023 at 2:46pm

This part of his forecast has not held up well.

I’d say yes and no. Compared to 100 years ago, people begin their careers far later than they did in Keynes’s time and end them far sooner. And while working, their hours and weeks are shorter. Bored kids and retirees who are not sure how to fill their free hours is far from unknown.

But free markets always remain competitive. Firms that hire people who’d prefer to loaf as much as possible don’t do well in competition with ones that don’t. Which is why tenure is granted only after ~5 years of very hard work and companies start out new employees with only a couple weeks of vacation.

Pierre Lemieux

Apr 24 2023 at 3:11pm

Mark: You are right that Keynes was partly right. But he went a bit farther: he thought that people would work three hours a day on a five-day working week. He thought the boredom problem would be worse than what we see today, altough people would have had time to get used to dealing with this in the intervening 100 years.

Richard W Fulmer

Apr 24 2023 at 3:09pm

I think that relative dirigisme matters. The United States is hardly the epitome of economic freedom, but it is far freer than are many other countries, and we benefit enormously from refugees and capital fleeing such nations.

Craig

Apr 24 2023 at 4:41pm

“Anther hypothesis along the same lines is that the social, economic, and political institutions that respect or promote individual liberty and free markets are very resilient”

“Yet, we do not know if and where a breaking point exists at which prosperity would stop or reverse like in, say, Argentina or Venezuela”

I think there is definitely something to be said for this with respect to the US. Personally I have been surprised at just how much government mismanagement has had on relative prosperity in the US. I can only attribute it to much legacy goodwill. Right now a 10 year treasury is trading at 3.5% with trillion dollar deficits, extremely little history of fiscal responsibility in my entire lifetime, a recent inflation spike up to 9%+, $30tn+ in debt.

And people are still lining up to buy this garbage. That’s because ultimately the US govt’s creditors think the US govt will do the ‘right thing’ by its creditors.

Other countries have done what the US govt has done and the result is the typical Latin American inflationista banana republic, or Turkey, or whatnot. What’s the break point? The issue is one of faith. Right now the money supply is decreasing on a Y/Y basis, disinflation will prevail. Long term, US govt debt is not sustainable, how will the US govt treat with it? My prediction is inflation and eventually the bond market will roll over. Even today one of the words of the day is ‘de-dollarization’.

Andrew_FL

Apr 24 2023 at 5:32pm

I’m somewhere between “data hypothesis” and “counterfactual hypothesis”

I can believe that the 19th century data is misleading of our interpretation of it is (also that the same is probably true, to different degree and different ways, of the 20th/21st)

But I also think the counterfactual is just logically correct, although I can’t really fathom the difference being huge because a hugely richer society than the richest society in human history is inherently difficult to conceptualize.

Mark Brady

Apr 24 2023 at 7:04pm

Some of you may be interested to read (or at least look at) Lorenzo Pecchi and Gustavo Piga, eds., Revisiting Keynes (MIT Press, 2008). This is a compilation of essays by economists on the extent to which Keynes’s 1930 essay had held up since its original publication.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Revisiting_Keynes/brofEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

Knut P. Heen

Apr 25 2023 at 5:23am

People living in the 1930s would perhaps have defined many of today’s “jobs” as “leisure”?

john hare

Apr 25 2023 at 5:58pm

The tools and techniques available today in concrete construction can be leisurely compared to that in the 1970s when I started. Pumps vs. wheelbarrows. Excavator vs. shovels. Laser vs. transit. Power steel cutters vs. manual. And so on for pages where I don’t have to work as hard (even if I were able) as I did 40 odd years ago to get the same job done.

Pierre Lemieux

Apr 25 2023 at 6:43pm

Knut and John: It’s a slightly different problem, though. What you describe is still work, that is, a cost incurred in order to obtain some final goods ([money for] consumptions goods you want to enjoy or the cabin you have built for yourself). Work has become easier, the cost has decreased, and this is good. But leisure is what you want do when you don’t have to work. It is true, though, that an increase in real income, the gain in utility minus the cost in utility, includes all that.

Craig

Apr 25 2023 at 8:06pm

Although I must say in this day and age the distinction between work/leisure has become increasingly blurred!

Dylan

Apr 26 2023 at 7:00am

I do essentially the same thing for my work and leisure time. I find that I’m much more motivated though when I’m not getting paid.

nobody.really

Apr 26 2023 at 7:48am

It hadn’t occurred to me that sex workers would read econ blogs. Good for you!

Craig

Apr 26 2023 at 8:32am

Find a job you enjoy doing, and you will never have to work a day in your life!

Roger McKinney

Apr 25 2023 at 9:49am

The effect of regulations may have a long lag time. Many economists see the last 2 decades as periods of stagnation. One of the main evils of regulation is that most are written to protect large corporations. That has created oligopolies, or cartels that don’t compete on price. And by shutting out smaller competitors they reduce demand for workers and keep wages lower than they would have been. Some economists estimate that Regulations cost businesses $2 trillion per year to comply.

Comments are closed.