Everybody should be impressed when comparing the effects of the 18th-19th-century Industrial Revolution with the previous world depicted by, say, 15th-century poet François Villon. This world was one of dire and hopeless poverty for ordinary people, with few exceptions. Villon imagined that, if he had any money, he would make a bequest to “three naked little children” (trois petits enfants tout nus) who might not otherwise survive the winter, and to remark:

II n’est tresor que de vivre à son aise.

(The only treasure is to live comfortably.)

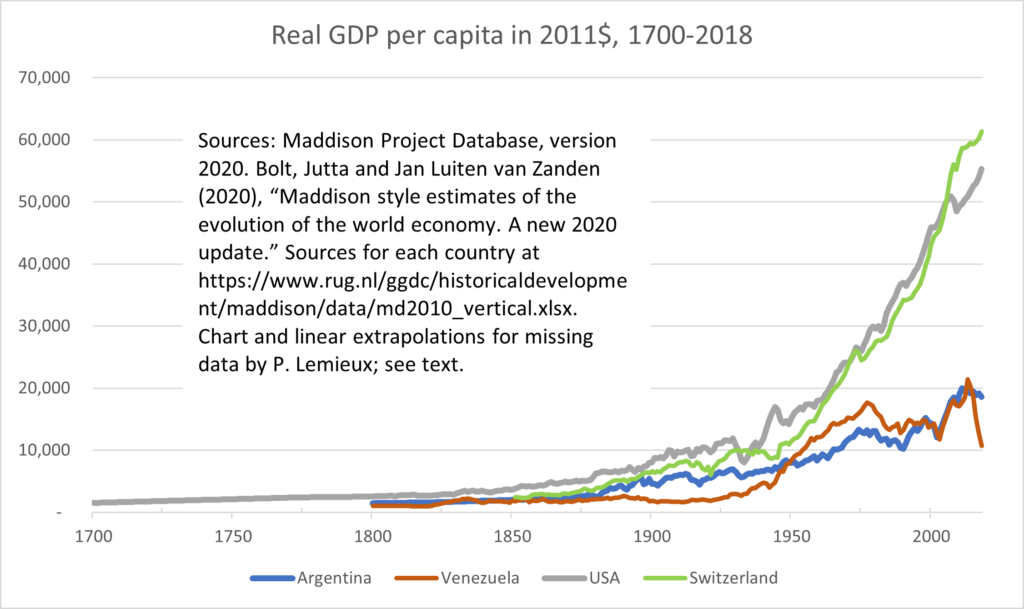

In the wake of the Enlightenment, the Industrial Revolution produced the Great Enrichment, realizing the dream of comfort and wealth for ordinary people, as illustrated on my chart below. The great increase in productivity benefited all industries, not only manufacturing.

My chart is built on the basis of long-term estimates of economic growth by the Maddison Project, which updates the pioneering work of Angus Maddison (1926-2010). The standard of living over time is measured with gross domestic product (or income) per capita. Many caveats are of course in order regarding historical estimates of the complex concept of gross domestic product developed in the 20th century. But the broad trends drawn by the Maddison estimates are consistent with how other historical sources depict the former epochs of mankind.

To keep the chart readable, I start it at the beginning of the 18th century and graph only two countries, the United States and Switzerland, as representative of the effects of the Industrial Revolution. This momentous event actually started in the United Kingdom and the Low Countries, and most Western countries rapidly followed. For many territories corresponding to today’s countries, the Maddison Project (like Maddison’s original estimates) provide some data points back to year 1 CE. Extending my chart backward in time would show that there was generally no economic growth between year 1 and the 17th century, that is, we would see a long visually flat line at roughly the level of the American standard of living in 1650 (i.e. $897). For example, the GDP per capita of the inhabitants of current Switzerland is estimated to have been $956 in year 1. (The Maddison Project does not provide estimates where no recorded history exists at all.)

It is generally recognized that the unprecedented growth unleashed by the Industrial Revolution finds its source the in economic, political, and social institutions that protected property rights and allowed or promoted free enterprise and free markets. I have a bit more to say about this in the forthcoming issue of Regulation.

Another phenomenon the chart emphasizes is the interrupted industrial revolutions of some countries. For example, consider Argentina, whose economy seemed to be taking off along with other Western countries until the end of the 19th century. But then, with one authoritarian or populist regime after another, economic growth slowed down. As a consequence, real GDP per capita in Argentina is now barely more than one-third of the US level. Or consider Venezuela, whose industrial revolution started only in the mid-20th century and stopped a few decades later. Helped by higher oil prices, GDP per capita increased a bit under the elected dictatorship of Hugo Chavez (from 1999 to 2013), but plunged dramatically under that of Nicolas Maduro (2013 to now). Venezuela’s GDP per capita is now only 20% of America’s. (For perspective, China’s GDP per capita is one fourth of the American level.)

The unresolved question is whether and under which conditions the prosperous civilization built by the Industrial Revolution could crash and bring mankind back to the the Middle Ages or Antiquity, as Jose Ortega y Gasset feared (see my review of his The Revolt of the Masses in the forthcoming issue of Regulation). Nobel prize-winning economic historian Douglass North expressed somewhat similar fears (see his Understanding the Process of Economic Change [Princeton University Press, 2005], pp. 77-78):

The long run economic success of western economies has induced a widespread belief that economic growth now is built into the system, in contrast to the experience of the previous ten millenia [sic] when growth was episodic and frequently non-existent. … It is still an open question whether in fact that supposition is correct. It is important to understand that experiencing economic growth for fifteen or twenty years is not a guarantee that it is built into the system.

Sources for each country at https://www.rug.nl/ggdc/historicaldevelopment/maddison/data/md2010_vertical.xlsx.

READER COMMENTS

john hare

Apr 16 2023 at 12:23pm

Bringing mankind back to the middle ages would entail what percentage of the population dying?? Even agriculture is massively dependent on our current capabilities.

Pierre Lemieux

Apr 16 2023 at 1:26pm

John: Very relevant question and comment. Using the Maddison Project data, world population was 1.1 billion in 1820, the year when the start of the Industrial Revolution take-off is often dated. It is today 7.5 billion. Thus population would have to be reduced (through diseases and other causes of death) by 87%. Many observers, including Hayek, have argued that this would be the cost of the destruction of free societies.

Craig

Apr 16 2023 at 11:56pm

If the yield per acre dropped to survive places would have to put more acres into agricultural production. The town I grew up in NJ is now a typical suburb but was a farming town. If some type of economic catastrophe hit putting food security in jeopardy I could definitely see that town having a denser core surrounded by fields. The sprawl would end. In 1900 40-50% of the population listed their occupation as farmer. If the US returned to that the country would be much poorer, but would it be able to feed itself and sustain 320mn people?

Andrew_FL

Apr 16 2023 at 2:54pm

It doesn’t really change your points but you are wiser than you realize not to graph Maddison’s pre-1800 data for most countries or pre 1700 data for the few countries about which somewhat real data even exists for the 18th century. Actually reading Maddison’s papers reveals that most of the pre-1850 data for most of the world is guesswork and conjecture. Inferences are made based on arbitrary assumptions and indirect evidence.

Here’s an example, to quote Maddison:

“For most of the rest of Asia, it seemed reasonable here to assume that the level of per capita income was similar to that in China and showed no great change from the first century to the year 1000.”

It is a stretch to say zero growth is finding of Maddison when it is often an assumption of Maddison’s.

Economic growth most probably was very small for the centuries preceding the industrial revolution. But on the question of exactly how small, IMO Maddison can tell us very little.

About Argentina, I like this comparison: in 1945, Argentina had a GDP/capita about equal to Belgium. In 2018, about equal to Belarus.

Craig

Apr 16 2023 at 11:00pm

I think I know where the Argentine comparison is headed, but honestly 1945 Belgian GDP per caputa cN’t be that good given WW2. Early part of the year Battle of the Bulge still happening

Andrew_FL

Apr 17 2023 at 9:54am

You’re right, Belgian GDP per capita was definitely lower in 1945 than it might have been without the war, although the worst year was apparently 1943, not 1945. If I estimate a trend line between 1900 and 1959, 1945 is about 75% of trend. Argentina in 1945 was also about 1.25x Chilean GDP per capita and 1.09x Norwegian GDP per capita, and 86% of Denmark level.

The thing is that even with the war going on, the highest GDP per capita countries ca 1945 is dominated belligerents and occupied countries! The other country Argentina was close to in GDP in 1945 was Germany.

Of course, I could also pick an earlier year to do the comparison. trying to avoid World War I and the Depression as well, if I go to 1913, Argentina is roughly halfway between Germany and Denmark. In 1929, roughly between Sweden and France.

Pierre Lemieux

Apr 17 2023 at 11:42am

Andrew: You note:

This is however an artifact from including in GDP gross government expenditures on goods and services, instead of only their value added. Many economists, including Simon Kuznets himself, did not agree with that practice. See my “What You Always Wanted to Know about GDP But Were Afraid to Ask.”

Andrew_FL

Apr 17 2023 at 11:57am

Pierre-to be clear, most of the list of top GDP per capita countries during the war and immediately before the war looks very similar. You’re right that GDP figures are inflated during the war for some countries, especially the US. If I compare in 1939, Argentina ranks 14th just above Austria and somewhat below Norway. So Argentina’s peer countries in GDP per capita terms were a similar set of countries before and during the war.

Pierre Lemieux

Apr 17 2023 at 11:29am

Andrew: You are right to remind us of the fragility of these estimates. Maddison would probably reply that intuitions are even more fragile and difficult to debunk.

Craig

Apr 16 2023 at 11:43pm

“The unresolved question is whether and under which conditions the prosperous civilization built by the Industrial Revolution could crash and bring mankind back to the the Middle Ages or Antiquity, as Jose Ortega y Gasset feared”

Humanity today has an inheritance of knowledge that could have greatly mitigated things like the Black Death. Look at COVID, which as awful as it is and as divisive as it is, well bottom line it definitely beat self-flaggelation. As late as the Victorian era cosmetics would have lead, mercury, arsenic, and ammonia.

I would say that it really would boil down to energy. If we presume that all fossil fuels were completely depleted and couldn’t be used would humanity be able to do better than windmills, watermills, sailing ships and oxen? I’d say nuclear, geothermal, solar etc very well might cost more per kwh or btu, but still wouldn’t set humanity back to medieval living standards.

Mactoul

Apr 17 2023 at 12:05am

I wonder if you ever read David Stove’s critique of the Enlightenment. He thinks enlightenment had nothing to do with the industrial growth of 18th century onwards and the main fruit of enlightenment was the cult of equality that is counter productive to the industrial growth.

Stove is very readable.

Jon Murphy

Apr 17 2023 at 4:46am

Interesting. What’s Stove’s alternative hypothesis?

Mactoul

Apr 17 2023 at 5:51am

Stove made distinction between the Enlightenment ideas– dignity, equality, liberty and the technological advancements.

Jon Murphy

Apr 17 2023 at 7:52am

Ok but what’s his alternative hypothesis as to why the growth happened when it did and not the prior thousands of years?

Craig

Apr 17 2023 at 11:04am

I think it might be a good place to pose the question about why Rome didn’t ultimately industrialize. One can look at Hero’s engine and the mills at Massilia and other proto-industrial endeavors and perhaps come to the conclusion that the Romans were on a path to industrialization. My short take on this is that Roman development was short circuited by the Crisis of the Third Century and to a certain extent Gibbon might give compelling reasons, but at the end of the day one has to give some credit to the Goths and Huns as well as plagues.

Pierre Lemieux

Apr 17 2023 at 11:15am

Craig: A big part of the answer to your question is in Walter Scheidel’s Escape from Rome. My Regulation review will give you a taste, but only a taste. I would say the book is a must-read for a history buff and national divorce advocate!

Jon Murphy

Apr 17 2023 at 12:38pm

Those didn’t help, but I’m not sure they can explain the failure of Rome to industrialize. Plagues and invasion are nothing new.

The Crisis could be a major cause as it dried up capital.

Craig

Apr 17 2023 at 3:00pm

I would even say it was the Antonine Plague which is before 3rd century. The impact of these events can even be seen in ice core samples measuring metal pollution. One sawmill (and they had marble cutting mills too) at Hierapolis had all of the precursors except the steam engine itself. And that existed during the Crisis of the Third Century. The issue is one of probabilities. And even with the crisis, there was some probability of industrialization. Of course it didn’t happen and so its difficult today to assign a non-zero probability to an event we know didn’t happen.

The plagues even make it difficult for the Roman army to repel the barbarians. The Antonine plague was the first one during the time of the principate and Marcus Aurelius was recruiting anybody with a pulse to fight because it wasn’t 5-10% less soldiers, it was apparently devastating enough that there basically was NO army and the Maromanni were coming. And Marcus Aurelius recruited criminals, Germans, gladiators….

Before this Roman arms were almost always superior and the story was one of expansion, after which quite the reverse. Indeed there are many who opine that the crisis was such that the fact Rome didn’t fall for hundreds of years was a testament to how strong it was at that time. Imagine the Mexican Army taking San Diego, the Canadians taking Detroit and NYC just lost 64% of its population to bubonic plague (That’s what I just read Alexandria lost in the later plague). In that environment, somebody in New Brunswick, NJ might invent the cure for cancer. The possibility exists, but the probability is far less. And today of course humanity has a cure for bubonic plague, or maybe it was smallpox (they don’t know), but there’s vaccines now. Back then?

The environment was such that the probability of the necessary subsequent innovation happening were much, much lower and the history previous does suggest that from 200-473AD the Romans would’ve had a decent chance at industrializing if those things didn’t happen.

Jon Murphy

Apr 17 2023 at 4:33pm

Plagues are devastating, to be sure, but they’re too common to explain a lack of industrialization. Plus, plagues continued after industrialization. Indeed, it was because of industrialization that our ability to combat plagues improved.

So, I don’t think plagues, even as one as those that hit Rome, can explain the lack of industrialization

Craig

Apr 17 2023 at 5:21pm

“Plagues are devastating, to be sure, but they’re too common”

The Antonine was the FIRST one though. “The Antonine Plague was the first known pandemic impacting the Roman Empire. The plague, generally believed to be smallpox, was possibly brought by soldiers returning from the campaign in Western Asia, leading to catastrophic results for the Roman populace, whom had likely never been exposed to the disease before.”

“Plus, plagues continued after industrialization. ”

But the trick would be known. After the Antonine Plague, they still remembered the proto-industrialization. The sawmill I referred to before existed in the middle of the Crisis of the Third Century.

Pre-Antonine Plague the Romans were on a trajectory that within a couple hundred years they were probably going to industrialize, after which they were almost assuredly NOT going to industrialize, they were on a trajectory to Alaric and what would be an almost complete depopulation of Rome during the Gothic Wars.

”

The Roman Empire would keep going for another couple of centuries, but its economy never recovered. Some areas had lost up to a third of their population to the Antonine Plague, which left the Empire with both a smaller mining workforce and less economic demand for currency. The battered condition of the Roman economy is evident in the low levels of lead in ice layers from the plague years and the five centuries that followed.

“The nearly immediate and persistent emissions decline following major plague outbreaks suggests low societal resilience and far-reaching economic effects,” wrote McConnell and his colleagues.

The already-battered Roman economy took another hit during the Plague of Cyprian from 249 CE to 270 CE, which struck in the midst of a period of political turmoil called the Imperial Crisis. It dropped lead emissions to their lowest levels since 900 BCE. European lead production didn’t start to recover until the early medieval years, when mining resumed in France and Britain.” — https://arstechnica.com/science/2018/05/greenland-ice-cores-track-roman-lead-pollution-in-year-by-year-detail/

Craig

Apr 17 2023 at 5:25pm

Quick question for both Professors. The Antonine Plague was believed by the Romans to have been caused as a result of a Roman army desecrating a temple in an eastern campaign. Fact is they believed that so I might pose a question to both of you, “If you believe that your society is suffering from a pandemic because the Gods have cursed your society, what exactly do you think that might do to individual’s investment preference horizons?”

Jon Murphy

Apr 17 2023 at 5:41pm

There’s a signifigant difference between the first plague recorded that affected the Roman Empire (what your source says) and the first plague (what you say). The latter implies no disease existed prior to 165 AD.

Given the Empire would persist for another ~1,300 years (300 as the Empire centered in Rome and another 1000 as the Empire centered in Constantinople), I don’t think it had that much of an effect on time horizons.

But, if it did, then the problem is one of appeasing the gods.

Craig

Apr 17 2023 at 6:14pm

“There’s a signifigant difference between the first plague recorded that affected the Roman Empire (what your source says) and the first plague (what you say).”

I wrote this: “The Antonine was the FIRST one though. “The Antonine Plague was the first known pandemic impacting the Roman Empire….”

I am not writing that suggesting the Antonine Plague was the first plague of all time. I was aware they were qualifying it with the first one impacting the Roman Empire like that. But your point is that the plague couldn’t impact whatever propensity there might have been to industrialize because plagues were historically too common. My point is that doesn’t apply here because the Romans hadn’t experienced one yet. And when they did it put them on a completely different trajectory. Prior to the Antonine Plague the Pax Romana prevailed and there was generally an upward trajectory that very likely could have produced industrialization. After though it wasn’t, it was on a downward trajectory and one that was unlikely going to produce innovative change like industrialization.

Its a 500 year setback.

Its the first plague the Romans faced. And the point of course is that the plague

The latter implies no disease existed prior to 165 AD.”

But your point is that surely a pandemic couldn’t change the trajectory the Romans were on because pandemics were too common, but this was the FIRST one they faced,

Jon Murphy

Apr 18 2023 at 8:22am

I know that; I am saying that is a misinterpretation of the evidence you cite. The Romans had experienced plagues before. Plagues existed before 165AD. It was the first one recorded, but not the first one.

Further, a single data point does not determine the trend. You’d need to explain why plagues didn’t stop the Industrial Revolution despite several plagues being more deadly (adjusted for population) than the one in Rome.

Jon Murphy

Apr 18 2023 at 9:06am

Just to be perfectly clear, Craig:

I do not think you’re wrong to state the Plague had a major impact on both the economy and the psyche of Rome. It very probably did reduce economic growth. It’s also reasonable that, as you suggest, it reduced the average Roman’s time horizon.

I just question whether it can explain the lack of industrialization given the pattern does not hold outside of Rome. If plagues were a significant cause of lack of industrialization, then we would expect the bigger plagues (adjusted for population) that ravaged Europe and North America in the 1700s-1900s to have stopped industralization. But they didn’t.

Pierre Lemieux

Apr 18 2023 at 10:44am

Jon and Craig: Speaking of plages, we must not forget the Black Death of the 14th century. It was probably the worst plage in the history of mankind. It killed something like one-third the population of Europe. Yet, instead of compromising a future Great Enrichment, it turned out to be one of its most crucial precursors: by liberating the serfs, it created a labor market and increased the remuneration of labor; in other words, it promoted individual liberty. It may have done for labor freedom what Dutch financial markets did for investment in the 16th century. And, we now know, individual liberty is the basis of social institutions that allow prosperity. The Roman empire had a powerful one of those social institutions, private property, but was not hospitable enough to political anarchy (to follow up on Baechler and Scheidel).

Pierre Lemieux

Apr 17 2023 at 11:09am

Mactoul: To pursue Jon’s question, why didn’t the industrial revolution happen in China, where as late as the 15th century technology was in many ways more advance than in the West. I will give more hints in my forthcoming Regulation article. In the meantime, Mokyr and Scheidel (linked to in my post above) give the big picture.

Pierre Lemieux

Apr 17 2023 at 8:53pm

Craig: On why the Roman empire did not, and could not, be the locus of an Industrial Revolution, we may quote Jean Baechler (as Scheidel also quoted him) about the Western world around year 1000 of our era:

Craig

Apr 18 2023 at 1:11am

Well, I suppose it better it happened in a place which relied on the increased productivity to subjugate and subdue the world’s largest Empire!

Pierre Lemieux

Apr 18 2023 at 10:09am

Craig: What do you mean?

john hare

Apr 18 2023 at 5:43pm

I think Pierre was closing in on one of the answers earlier. A society based on slavery and exploitation has low likelihood of innovating their way into an industrial revolution.

I’ve noticed that companies that treat their employees poorly don’t innovate. When one extrapolates that to using slave labor as in many early societies, the incentives to innovate are reduced even further.

Mactoul

Apr 17 2023 at 1:09am

Can there be biological constraints on growth?

Population growth is slowing down and probably going to reverse itself globally, sooner or later.

Humans are already taking more than half of primary productivity ( which is energy fixed by primary producers). Where is margin for further growth?

Population growth is different in different populations and not all populations are equal regarding economic growth, though it is impolite in these circles.

But evolutionists discuss these questions all the time. Man is self-domesticated animal and some populations are more domesticated than others.

Jon Murphy

Apr 17 2023 at 4:49am

The evidence suggests a tighter connection to wealth rather than some biological constraint. After a certain level of wealth, people have fewer kids.

Warren Platts

Apr 18 2023 at 12:57am

According to Ricardo’s Malthusian theory of wages, wealth is a biological constraint. He posits a “natural wage” that’s set by custom that in turn depends on the overall opulence of the society. So when the market wage is well above the natural wage, population growth rises and vice versa. The problem is when the natural wage rises faster than the market wage. That’s why after a certain level of wealth (basically where we’re at), people have fewer kids. That is, the current level of opulence has caused the natural wage to exceed the market wage, and thus, paradoxically, despite record wealth, people can only afford to have fewer kids.

Jon Murphy

Apr 18 2023 at 7:12am

Fine, but given that theory was disproven about 200 years ago, it’s irrelevant. Might as well cite Miasma Theory while you’re at it. That was disproven about the same time.

Warren Platts

Apr 18 2023 at 2:49pm

{citation needed} You’re conflating Ricardo’s theory of wages with his labor theory of value. They are not the same thing.

Warren Platts

Apr 18 2023 at 3:06pm

I should probably elaborate a bit. The falsified cartoon version of the labor theory of value is that the value of a widget is measured in the number of hours that goes into producing the widget. (Albeit an hour of an Englishman’s labor is worth a lot more than an hour of a Russian’s labor, right?)

But what exactly is the laborer laboring for? More labor? No. He’s working for money, also known as wages. Ricardo doesn’t say the wage level of labor is labor. No, he explicitly said the real wage level is what those wages will buy in goods & services.

Then he makes a distinction between the natural wage level and the market wage level. Meantime, Ricardo’s natural wage was cribbed straight out of Adam Smith. I doubt, Jon, that you think that theory was falsified, and presumably you have no problem with ordinary market wage levels.

Jon Murphy

Apr 18 2023 at 7:05pm

Citations are not needed for common knowledge.

Pierre Lemieux

Apr 17 2023 at 11:54am

Mactoul: This is what the environmentalists of the 1960s and 1970s thought. I previously noted that

Warren Platts

Apr 18 2023 at 12:45am

Mactoul’s point still stands. Primary productivity is all plant biomass generated by photosynthesis. We’re using half of that now. The rest of nature gets the other half. I guess there are geoengineering techniques we could and probably should try, like iron fertilization of the oceans, but man, the sheer amount of meat embodied in human bodies is hard to comprehend until you consider that the human plus livestock biomass is like 18 times more than all wild mammals and birds combined.

The doomers will always be wrong until they’re right.

Pierre Lemieux

Apr 18 2023 at 10:51am

Warren: It is difficult to study society without factoring in social institutions and incentives. You then get an Ehrlich-type biological mumbo jumbo.

Warren Platts

Apr 18 2023 at 3:41pm

I agree, but ignore biological considerations at your own peril. If you extrapolate the current global population growth rate of 1% per year into the future, in a mere 500 years, you get a trillion humans. The body heat alone would equal 10^14 Watts. For comparison, total solar insolation is 5 x 10^14 Watts. At that point you’re battling thermodynamics, not biology..

But thankfully, due to social institutions and incentives, as you say, it looks like the human population will top out on its own before hitting any extrasocial walls. That fact can only be applauded because there are indeed Limits to Growth..

Jon Murphy

Apr 18 2023 at 7:06pm

I think this is an interesting statement. How would one know one is wrong if they believed this statement?

Matthias

Apr 17 2023 at 4:46am

I would suggest using a log scale. Otherwise you will always get a flat looking section at the beginning of any exponential growth.

Pierre Lemieux

Apr 17 2023 at 11:27am

Matthias: I thought about that. One drawback would be that a (semi-)log scale hides the effects of compounded growth to anybody not familiar with logarithms.

Jose Pablo

Apr 17 2023 at 4:47pm

For, basically, the same reason that you plot this comparison in terms of GDP per capita (and not just GDP) it might be useful to compare this evolution with the growth in the “capital stock”.

The result, basically an historical evolution of TFP in different countries could give some interesting insights on the discussion about the reason for the differences in economic growth you are pointing at.

[If you are aware of such an analysis, Pierre, as you, very likely, are, please, point it out at me]

Sure, technology plays a role and we know, since Acemoglu and Robinson, that institutions definitely play an outsized role. Among these, surely is having relatively free markets able to allocate capital “the best we can” (which is, maybe, different from the “absolute optimal allocation” that some of us are able to imagine but is never reached … and yet they keep trying: see the “Chips Act”)

Pierre Lemieux

Apr 17 2023 at 8:34pm

Jose: I am not aware of long historical data of the stock of capital, but there must be some cliometricians who have tried to make modest estimates. The Maddison project does not have such a category. I would be interested if you find something too! Even nowadays, capital is one of the most difficult economic variables to measure, especially if human capital is included. The only to measure the human capital of a top surgeon is to observe that he earns, say, $1 million a year, so that his human capital must be worth something like $10 million.

Jose Pablo

Apr 18 2023 at 1:51pm

10 million pretax … so let’s say 5-6 million as “net human capital”, tops

Jose Pablo

Apr 18 2023 at 2:02pm

Just vaguely related, but loving this Selgin’s idea of using monetary policy to turn the price index into a kind of “productivity tracker” (more or less)

https://www.mercatus.org/macro-musings/george-selgin-productivity-norm-deflation-and-monetary-history

(Courtesy of your co-bloger Scott Sumner)

Comments are closed.