Supply vs Quantity Supplied: Housing Edition

By:

I’ve never been accused of being hesitant to nitpick (and if anyone ever did make that accusation, I’d nitpick it apart!), but sometimes what seems like a nitpick is actually an important point. Economists often make what seems like a nitpicky point to the non-economist. It usually takes a form like this: “Actually, Tesla’s recent price reductions won’t increase the demand for Tesla vehicles – it will increase the quantity demanded.” Or, we might say that the recent spike in egg prices doesn’t reduce demand for eggs, it only reduces the quantity of eggs demanded. (Insert obligatory “all else being equal” clause here, and please mentally carry it forward for the remainder of the post! It will save me a lot of keystrokes.)

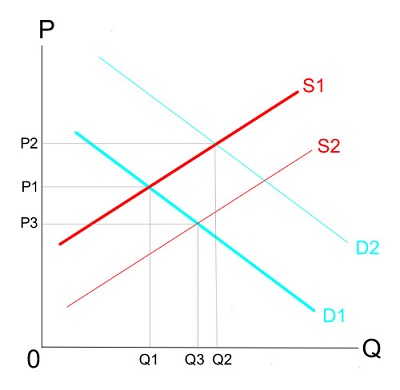

Increases or decreases in demand mean the demand curve has shifted right or left. The same is true for changes in supply. Increases or decreases in quantity demanded (or supplied) means moving up (or down) the curve, without shifting its position. We could also speak of the change in elasticity of supply and demand, which changes how steep the curves are, but for now we can ignore that complication. Let’s just stick with those two ideas – shifting the curves and moving along the curves.

I’ve been told that a sign you’ve mastered learning a new language is when you experience and understand people speaking that language in your dreams. I wouldn’t know – I lived in Japan for an extended period, and I only learned to say about four words of Japanese that whole time. But in that spirit, a sign that you’ve fully absorbed and understood the importance of this seemingly nitpicky distinction is this – the phrase “building new houses doesn’t increase the housing supply” doesn’t sound even slightly odd to you.

Let me try to unpack that. Demand, roughly, means how much we want something. A spike in egg prices will lead people to buy fewer eggs, but that’s not quite the same as saying people want eggs less than they used to. It only means people are less willing (or able) to buy as many eggs at the current price compared to before. Their demand for eggs hasn’t changed, but the quantity demanded has. The demand curve remains unmoved. Demand increases (or decreases) when we want something more (or less).

Supply, roughly, means the capacity to produce something. Sticking with the example of eggs for now, a wave of avian flu has decreased egg production capacity – the supply curve has shifted to the left, reflecting the reduced capacity. If demand for eggs were to sharply decrease, that is, if people were to find eggs less desirable than before, perhaps due to sudden widespread health concerns about eggs or increased adoption of plant-based diets, the demand curve would shift left and the equilibrium price would fall, but the supply curve would stay put. If this happens, the quantity of eggs supplied would also drop, but the supply curve would stay put. The capacity for egg production wouldn’t have changed, but suppliers aren’t willing to produce as many eggs at the new lower price.

This basic idea leads to a common confusion I see from NIMBYs about the effects of building new housing. Increasing the supply requires shifting the supply curve – or, in other words, increasing our capacity to build new housing. That’s not the same as merely building more housing in and of itself.

Imagine a place where, due to tight regulations, the supply of housing is fixed. Your first impulse might be to think this means no new housing can be built, but that’s not quite right. It just means that the supply curve cannot shift. With a fixed supply curve, the quantity supplied can still increase. When the demand curve shifts further to the right and the supply curve stays fixed, quantity supplied can increase – but the equilibrium price will increase along with it. This means that in places where the supply curve is so tightly constrained as to be effectively fixed, new houses will be built only when demanded by people willing and able to pay top dollar for them – that is, the rich. This means that despite new housing being built, the supply of housing hasn’t increased.

For this place to increase the housing supply, as opposed to merely increasing the quantity of housing supplied, the housing market would need to be deregulated in a way that increases the capacity to build housing above what it was before. This can take the form of removing restrictions on multifamily units or limits on how tall apartment buildings can be, or eliminating minimum lot sizes, or streamlining a laborious and expensive approval process to build housing. If these kinds of measures were to be taken, then we can say that the housing supply has increased even prior to any new construction.

Missing this seemingly nitpicky distinction is the source of the common confusion among many of the NIMBY types I mentioned before. They might see a place where housing is expensive (due to restricted supply), but they also notice that new housing is still being built. But this new housing, far from making housing more affordable, is almost exclusively expensive housing, only affordable by the rich. This, in their mind, undercuts the argument that increasing the housing supply will lower housing prices – because they don’t comprehend the difference between “increasing the housing supply” and merely “building more housing” – that is, the difference between an increase in supply and an increase in the quantity supplied.

Kevin Corcoran is a Marine Corps veteran and a consultant in healthcare economics and analytics and holds a Bachelor of Science in Economics from George Mason University.