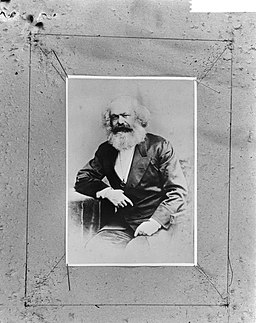

Karl Marx

1818-1883

Karl Marx was communism’s most zealous intellectual advocate. His comprehensive writings on the subject laid the foundation for later political leaders, notably V. I. Lenin and Mao Tse-tung, to impose communism on more than twenty countries.

Marx was born in Trier, Prussia (now Germany), in 1818. He studied philosophy at universities in Bonn and Berlin, earning his doctorate in Jena at the age of twenty-three. His early radicalism, first as a member of the Young Hegelians, then as editor of a newspaper suppressed for its derisive social and political content, preempted any career aspirations in academia and forced him to flee to Paris in 1843. It was then that Marx cemented his lifelong friendship with Friedrich Engels. In 1849 Marx moved to London, where he continued to study and write, drawing heavily on works by David Ricardo and Adam Smith. Marx died in London in 1883 in somewhat impoverished surroundings. Most of his adult life, he relied on Engels for financial support.

At the request of the Communist League, Marx and Engels coauthored their most famous work, “The Communist Manifesto,” published in 1848. A call to arms for the proletariat—“Workers of the world, unite!”—the manifesto set down the principles on which communism was to evolve. Marx held that history was a series of class struggles between owners of capital (capitalists) and workers (the proletariat). As wealth became more concentrated in the hands of a few capitalists, he thought, the ranks of an increasingly dissatisfied proletariat would swell, leading to bloody revolution and eventually a classless society.

It has become fashionable to think that Karl Marx was not mainly an economist but instead integrated various disciplines—economics, sociology, political science, history, and so on—into his philosophy. But Mark Blaug, a noted historian of economic thought, points out that Marx wrote “no more than a dozen pages on the concept of social class, the theory of the state, and the materialist conception of history” while he wrote “literally 10,000 pages on economics pure and simple.”1

According to Marx, capitalism contained the seeds of its own destruction. Communism was the inevitable end to the process of evolution begun with feudalism and passing through capitalism and socialism. Marx wrote extensively about the economic causes of this process in Capital. Volume one was published in 1867 and the later two volumes, heavily edited by Engels, were published posthumously in 1885 and 1894.

The labor theory of value, decreasing rates of profit, and increasing concentration of wealth are key components of Marx’s economic thought. His comprehensive treatment of capitalism stands in stark contrast, however, to his treatment of socialism and communism, which Marx handled only superficially. He declined to speculate on how those two economic systems would operate.

About the Author

Janet Beales Kaidantzis was assistant editor of The Fortune Encyclopedia of Economics.

Selected Works

Footnotes

Mark Blaug, Great Economists before Keynes (Highlander, N.J.: Humanities Press International, 1986), p. 156.