At risk of taxing readers’ patience, here’s my rejoinder to Mike Huemer’s last guest post on the ethical treatment of animals. He’s in blockquotes, I’m not.

My main reactions:

I. The argument from insects has too many controversial assumptions to

be useful. We should instead look more directly at Bryan’s theoretical

account of how factory farming could be acceptable.

My argument may not change the minds of people who are convinced that factory farming is unacceptable, but I think it’s very useful at (a) changing the minds of people who are genuinely undecided, and (b) clarifying the views of people who have modest doubts about conventional treatment of animals.

II. That theory is ad hoc and lacks intrinsic intuitive or theoretical plausibility.

III. There are much more natural theories, which don’t support factory farming.

Disagree on both counts; see below.

I.

To elaborate on (I), it looks like (after the explanations in his latest post), Bryan is assuming:

a. Insects feel pain that is qualitatively like the suffering that, e.g., cows on factory farms feel.

b. If (a) is true, it is still permissible to kill bugs

indiscriminately, e.g., we don’t even have good reason to reduce our

driving by 10%.(a) and (b) are too controversial to be good

starting points to try to figure out other controversial animal ethics

issues. I and (I think) most others reject (a);

You might be right about how many people believe (a), but I suspect my view is actually more common. Pain has great evolutionary value. So why wouldn’t bugs feel pain?

I also think (b) is very

non-obvious (especially to animal welfare advocates).

As my original post noted, even conscientious people like Mike put little mental effort into investigating whether bugs feel pain. Which to me strongly suggests they find (b) pretty obvious.

Finally, note

that most animal welfare advocates claim that factory farming is wrong

because of the great suffering of animals on factory farms (not just

because of the killing of the animals), which is mostly due to the

conditions in which they are raised. Bugs aren’t raised in such

conditions, and the amount of pain a bug would endure upon being hit by a

car (if it has any pain at all) might be less than the pain it would

normally endure from a natural death. So I think Bryan would also have

to use assumption (c):

I haven’t investigated how horribly bugs suffer when humans accidentally kill them. But it seems entirely possible that humans condemn trillions of bugs to excruciating, drawn-out deaths every year. My moral theory implies there’s little need for me to investigate this issue. But if you really doubt (b), it’s a vital question. And since animal welfare advocates put little time into investigating (b), I infer they probably tacitly agree with me.

c. If factory farming is wrong, it’s wrong

because it’s wrong to painfully kill sentient beings, not, e.g.,

because it’s wrong to raise them in conditions of almost constant

suffering, nor because it’s wrong to create beings with net negative

utility, etc.

I could be wrong, but I think most people – regardless of their views on the ethical treatment of animals – would see little difference between these moral theories. Either you find them all plausible, or you find none plausible. Hence (c) is barely at issue.

II.

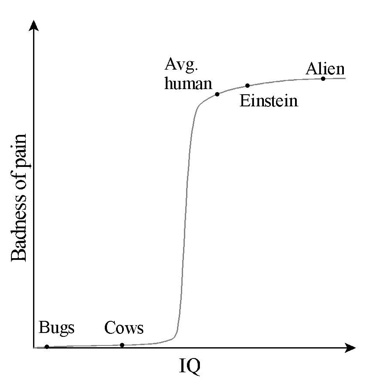

What

would be more promising? Let’s just look at Bryan’s account of the

badness of pain and suffering. (Note: I include all forms of suffering

as bad, not merely sensory pain.) I think his view must be something

like what the graph below depicts.

As your intelligence increases, the moral badness of your pain increases. But it’s a non-linear function. In particular:

i. The graph starts out almost horizontal. But somewhere between the

intelligence of a typical cow and that of a typical human, the graph

takes a sharp upturn, soaring up about a million times higher than where

it was for the cow IQ. This is required in order to say that the pain

of billions of farm animals is unimportant, and yet also claim that

similar pain for (a much smaller number of) humans is very important.ii. But then the graph very quickly turns almost horizontal again. This

is required in order to make it so that the interests of a very smart

human, such as Albert Einstein, don’t wind up being vastly more

important than those of the rest of us. Also, so that even smarter

aliens can’t inflict great pain on us for the sake of minor amusements

for themselves.Sure, this is a logically possible (not

contradictory) view.

Your graph accurately describes my view.

However, it’s also very plausible to me that the gap in intelligence between cows and the average human is so enormous that even a linear value function would yield similar results. This is trivially true on a conventional IQ test, where all bugs and cows would score zero. But it seems substantively true for any reasonable intelligence test: Bugs’ and cows’ ability to evaluate or construct even simple logical arguments stems from their deficient intellects, not inability to communicate. Or at least that seems clear to me.

But it is very odd and (to me) hard to believe. It

isn’t obvious to begin with why IQ makes a difference to the badness of

pain. But assuming it does, features (i) and (ii) above are very odd. Is

there any explanation of either of these things? Can someone even think

of a possible explanation? If you just think about this theory on its

own (without considering, for example, how it impacts your own interests

or what it implies about your own behavior), would anyone have thought

this was how it worked? Would anyone find this intuitively obvious? As a

famous ethical intuiter, I must say that this doesn’t strike me as

intuitive at all.

Then we have a deep clash of intuitions. My bug hypotheticals were meant to overcome such clashes. But if those seem lame to you, we are at an impasse.

Now, that graph might be a fair account of most people’s implicit attitudes. But what is the best explanation for that:

1) That we have directly intuited the brute, unexplained moral facts that the above graph depicts, or

2) That we are biased?I think we can know that explanation (1) is not the case. We can know

that because we can just think about the major claims in this theory,

and see if they’re self-evident. They aren’t.

Again, the idea that the well-being of creatures of human intelligence is much more morally important than the well-being of cows or bugs seems quite self-evident to me. And it also seems self-evident to the vast majority of creatures capable of comprehending the idea.

To me, explanation

(2) thrusts itself forward. How convenient that this drastic upturn in

moral significance occurs after the IQ level of all the animals we like

the taste of, but before the IQ level of any of us. Good thing the

inexplicable upturn doesn’t occur between bug-IQ and cow-IQ (or even

earlier). Good thing it goes up by a factor of a million before reaching

human IQ, and not just a factor of a hundred or a thousand, because

otherwise we’d have to modify our behavior anyway.And how

convenient again that the moral significance suddenly levels off again.

Good thing it doesn’t just keep going up, because then smart people or

even smarter aliens would be able to discount our suffering in the same

way that we discount the suffering of all the creatures whose suffering

we profit from.

I don’t see how your case for alleged bias is any stronger than the standard utilitarians’ claim that affluent First Worlders are too biased to see their moral duty to give all their surplus wealth to the global poor. The same goes for numerous other onerous-and-implausible moral duties, like our duty to create as many children as possible, or perhaps the duty to adopt as many needy orphans as possible.

In all of these cases, I admit, we should calmly reflect on our potential bias. I’ve genuinely tried. But even when I bend over backwards to adjust for my alleged bias against animals, I keep getting the same answer: They barely matter.

[…]

Imagine a person living in the slavery era,

who claims that the moral significance of a person’s well-being is

inversely related to their skin pigmentation (this is a brute moral fact

that you just have to see intuitively), and that the graph of moral

significance as a function of skin pigmentation takes a sudden, drastic

drop just after the pigmentation level of a suntanned European but

before that of a typical mulatto.

One of my strongest intuitions is that mental traits have a large effect on moral value, while physical traits do not. You really don’t share this intuition?

III.

A more natural

view would be, e.g., that the graph of “pain badness” versus IQ would

just be a line. Or maybe a simple concave or convex curve. But then we

wouldn’t be able to just carry on doing what is most convenient and

enjoyable for us.I mentioned, also, that the moral significance of

IQ was not obvious to me. But here is a much more plausible theory that

is in the same neighborhood. Degree of cognitive sophistication matters

to the badness of pain, because:1. There are degrees of consciousness (or self-awareness).

2. The more conscious a pain is, the worse it is. E.g., if you can

divert your attention from a pain that you’re having, it becomes less

bad. If there could be a completely unconscious pain, it wouldn’t be bad

at all.

3. The creatures we think of as less intelligent are also,

in general, less conscious. That is, all their mental states have a low

level of consciousness. (Perhaps bugs are completely non-conscious.)I think this theory is much more believable and less ad hoc than

Bryan’s theory. Point 2 strikes me as independently intuitive (unlike

the brute declaration that IQ matters to badness of pain). Points 1 and 3

strike me as reasonable, and while I wouldn’t say they are obviously

correct, I also don’t think there is anything odd or puzzling about

them.

What’s odd/puzzling to me is (3). Why would bugs or cows would be less conscious of their pain than we are? If anything, I’d think less intelligent creatures’ minds would focus on their physical survival, while smart creatures’ minds often wander to impractical topics.

This theory does not look like it was just designed to give us the

moral results that are convenient for us.Of course, the “cost” is

that this theory does not in fact give us the moral results that are

most convenient for us… But it just isn’t plausible that the

difference in level of consciousness is so great that the human pain is a

million times worse than the (otherwise similar) cow pain.

I fear we’re at an impasse. But let me say this: If Mike convinced me that animal pain were morally important, I would live as he does. I’d stop eating meat and wearing leather. I’d desperately search for a cruelty-free way to get dairy; but if I couldn’t, I’d even give up ice cream. I understand Mike.* What I don’t understand is people who claim to agree with him, but don’t repent and live a cruelty-free life.

* Well, almost. If I thought like Mike, I would also evangelically focus my intellectual career on the ethical treatment of animals, and spend thousands of hours reading biology journals to learn more about which animals feel how much pain. I know Mike hasn’t done the former, and doubt he’s done the latter. And I don’t understand why he hasn’t.

READER COMMENTS

David Condon

Oct 27 2016 at 1:50am

Wow. Bryan Caplan just bit a massive bullet. His argument implies that the mass genocide of all moderately, severely, and profoundly mentally disabled humans would be perfectly acceptable. He doesn’t even include any caveats; even the ones he mentioned earlier in the debate such as babies. It’s weird, but if I were in Huemer’s shoes I’d feel frustrated since it feels like Huemer is spending almost as much time describing Bryan’s position as he is defending his own position. And yes, that graph is what people like to tell themselves explains their behavior, but it doesn’t remotely resemble their actual behavior as I mentioned in an earlier thread.

Miguel Madeira

Oct 27 2016 at 4:26am

“I could be wrong, but I think most people – regardless of their views on the ethical treatment of animals – would see little difference between these moral theories. Either you find them all plausible, or you find none plausible. Hence (c) is barely at issue. ”

I think you are wrong – look to vast quantity of people who only want to eat meat of animals created “open range”, or with a minimum space, or… Much more, I think, than the people who totally refuse to eat meat.

Derek Conyngham

Oct 27 2016 at 6:06am

Human babies would also score zero on an IQ Test. Does that mean that there suffering barely matters morally?

I know that the typical answer to this question is that human babies will eventually become adults who will score above zero on an IQ Test. But this doesn’t intuitively seem to me to be relevant. Even if future IQ was relevant, do you think that that would make it permissible to kill and eat babies with terminal diseases?

Denver

Oct 27 2016 at 8:13am

I think IQ is framing this debate in the wrong way. I think a better way to look at it is anthropomorphism. Maybe not entirely in looks, but in mental states. Things that can express human-like cognitions, respect our rights, understand our communication, etc, we tend to take the “feeling of pain” of much more seriously. Cows can’t communicate these things. So while it’s clear they do feel pain, it’s not clear that their pain is of greater moral consequence than my pleasure of eating steak.

While I agree that Huemer is vastly underrating the difference in mental anthropomorphism between cows and bugs, and humans, and that there is a substantive difference between bugs and cows in IQ, I do think that communication plays a vital role.

For example, imagine a situation in which cows could magically talk, but retain their current levels of IQ. They would still act like cows, moo a lot, eat grass, etc, but if you tried to kill them, they could magically communicate their will to live: they might say “please don’t kill me” or something similar. In this scenario, is it permissible to kill cows?

Even if you think it would be still be permissible to kill cows, you would probably admit that it is significantly more of a moral quandary than before. And the only thing that changed was a cow’s ability to communicate.

Pedro Albuquerque

Oct 27 2016 at 8:34am

This discussion started with interesting opposing arguments that had potential for logical and ethical convergence, but unfortunately it ended up as an odd argument about using IQ testing to categorically equate cows to bugs and therefore to justify human cruelty to non-human life forms – an obvious intellectual dead end.

Matt Skene

Oct 27 2016 at 9:16am

Bryan, the fact that something would have evolutionary value doesn’t mean that creatures probably have it. Evolution almost never produces valuable characteristics that are more expensive to produce than necessary. For many creatures, a simple stimulus-response system is adequate to avoid threats and navigate their environment. Bugs can survive if they detect certain changes and respond to them. They don’t need to understand them, or think about them, or even have experiences. They can be little meat robots and survive. I have a hard time seeing what value experiences of pain would give to bugs over and above what a basic stimulus-response mechanism without pain as an addition would give to them.

I think pain only has value for creatures who need to be able to respond more intelligently to their environment to survive. Producing a sensation that persists so it can continue to motivate beyond the moment and that can serve in memory as a salient reminder to avoid things in the future has value if you can understand persisting conditions and know how to rectify them and if you have memory and plan for the future. I don’t think many animals that aren’t fairly complex in their lifestyles and behaviors have a need for more than a stimulus-response system without pain, so I don’t think pain would be likely to provide adequate evolutionary benefit to be found in them. Where that line is is difficult to determine, but I’d be very surprised if many bugs were across it, and very surprised if pigs and cows weren’t.

Miguel Madeira

Oct 27 2016 at 10:20am

“For example, imagine a situation in which cows could magically talk, but retain their current levels of IQ. They would still act like cows, moo a lot, eat grass, etc, but if you tried to kill them, they could magically communicate their will to live: they might say “please don’t kill me” or something similar. In this scenario, is it permissible to kill cows?

Even if you think it would be still be permissible to kill cows, you would probably admit that it is significantly more of a moral quandary than before. And the only thing that changed was a cow’s ability to communicate.”

I think this is more symbolic than anything else – look to the behavior of any relative of cows in the wildlife (like antelopes), when attacked by lions, wolfs, etc. All their behavior (running, protecting the newborns, etc.) meas that they know that they will be killed and don’t want that. There is a big difference between that and saying “please, don’t eat me!”?

Miguel Madeira

Oct 27 2016 at 10:28am

An aditional point could be – what we mean by “bugs”? Insects? All arthropods? All invertebrates? All invertebrates except those who belong to the filus Chordata (like lancelets)?

entirelyuseless

Oct 27 2016 at 10:42am

“His argument implies that the mass genocide of all moderately, severely, and profoundly mentally disabled humans would be perfectly acceptable.”

No, it doesn’t. Almost all such people can get pretty positive results on IQ tests, unlike cows and bugs; and even the ones who can’t, this is for physical reasons, not mental ones. All human beings who are not in a coma are far, far more intelligent than cows or bugs.

But the basic issue is that people are ignoring the idea of humanity and assuming that humans differ by degrees from other things. That’s ridiculous. It does not matter if it is true in some sense; it is not true in terms of moral consideration. We don’t kill those people because they are human. And the same thing applies to babies.

As for Derek’s comment that what something will become is morally irrelevant, that would justify bombing ongoing building sites because they are currently just as useless as rocks. But in fact that is pretty much just as wrong as bombing fully formed buildings. So he is just wrong: taking into account what a thing will become is completely morally intuitive, and we do it all the time in all sorts of situations.

Benjamin R Kennedy

Oct 27 2016 at 11:06am

A more interesting discussion is what does it mean for something to be “morally important”, and what can we learn from two sharp thinkers (intuitionists, no less!) coming to polar opposite conclusions on a pretty straightforward question

Andrew_FL

Oct 27 2016 at 11:39am

@Miguel Madeira-Or possibly only members of order Hemiptera?

(Intuitively it this context “bug” means terrestrial arthropod or other small land animal that humans casually kill often unintentionally and even unknowingly in the course of their daily lives. Things we step on, swallow, or splatter on our windshields.)

Chip Smith

Oct 27 2016 at 11:45am

Bryan,

I’m afraid it’s quite clear that you lost this debate. If you ever summon the fortitude to seriously look into the horror of factory farming, keep in mind that nut- and rice-based ice-creams are nearly as delicious, and getting better all the time.

Chip

Arthur

Oct 27 2016 at 12:04pm

Can we talk about Alzheimer’s for a moment? My grandmother’s intelligence, tragically, has declined to a level below most dogs. She perfectly capable of speech, but no longer able to form thoughts more complex than “yes” or “no.” Should I be able to torture or kill her for my own amusement? And if not, via Bryan’s intelligence theory, why not?

Andrew_FL

Oct 27 2016 at 1:29pm

That’s kind of a creepy place to leap, Arthur, but most people who eat cows don’t consider it morally acceptable to torture dogs, either.

Kelly

Oct 27 2016 at 1:34pm

I’ve been following along and I still don’t feel like Mr. Huemer addressed the crucial question at all, which is “Do bugs matter?” As someone who is admittedly not otherwise very familiar with the arguments on both sides, I was surprised that he just hand-waved it away. It seems to me that if bugs matter at all, then there is literally no graph you can draw that makes our current lack of attention to bugs acceptable. It seems like Mr. Huemer’s position on bugs requires a graph that looks exactly like Bryan’s, except with a huge drop off between cows and bugs rather than between cows and humans… and he seemed to think that Bryan’s graph was silly.

Because (probably) millions or billions of times more bugs are killed by our daily lives than cows, it seems like we should need to establish that bugs are millions or billions of times less sentient than cows, which seems non-obvious to me, hence my surprise at that argument’s dismissal.

austrartsua

Oct 27 2016 at 2:13pm

@Arthur

that is a tragedy. But it is not a fair comparison. You and your grandma’s friend’s and family feel great attachment to her, and to injure her body would be to cause them great harm. For the same reason, we have laws against the desecration of the bodies of people who have passed away. Desecration of a corpse causes great stress, not just to the family and friends, but to society as a whole.

Miguel Madeira

Oct 27 2016 at 2:26pm

entirelyuseless: “But the basic issue is that people are ignoring the idea of humanity and assuming that humans differ by degrees from other things. That’s ridiculous. It does not matter if it is true in some sense; it is not true in terms of moral consideration. We don’t kill those people because they are human. And the same thing applies to babies.”

This seems circular reasoning.

Hazel Meade

Oct 27 2016 at 2:37pm

Pain has great evolutionary value. So why wouldn’t bugs feel pain?

Bryan, you just massively failed to grasp the point that Huemer was trying to make. He’s not saying bugs don’t feel pain, but that the kind of suffering experienced by bugs is qualitatively different from the kind of suffering experienced by a mammal such as a cow.

Of course bugs feel pain. Nobody is denying that, but are they conscious of their own pain? Do they suffer emotionally as a result of feeling pain.

If I stub my toe I feel pain. If someone holds me down and smashes my foot with a hammer, I not only feel physical pain, I feel anger and betrayal and a desire to strike back at the person who did it.

My point, and Michaels is that there are degrees of suffering that only creatures with a higher level of consciousness (not intelligence!) is capable of. Bug don’t have internal lives. They don’t sit a contemplate their existance and wonder if there is a God and if so why he would fill their lives with pain. Humans do. And that has nothing to do with intelligence. Cows, probably experience at least some subjective perspective that their lives are filled with suffering for no explicable reason. They probably wonder what happens to their calves that are taken from them at birth and experience at least some emotional loss. Bug certainly do not. Again, you don’t have to be “intelligent” to feel those things. Mammals simply have cognitive capacities for suffering that don’t exist for insects.

That’s what Huemer is talking about. Not that bugs don’t feel pain but that the kind of physical pain they suffer is not morally equivalent to the kind of conscious suffering experienced by a cow.

Miguel Madeira

Oct 27 2016 at 2:41pm

“Because (probably) millions or billions of times more bugs are killed by our daily lives than cows”

Attending that what is being discussed is “factory farming” (and not any kind of use of an animal as food), I think that the “killing” is not the main point. There are relatively few bugs being created in situations comparable to “factory farming” (and the “animal rights” activists usually make protests against silk and carmine, and some are even against honey).

Maurizio

Oct 27 2016 at 2:50pm

@Bryan

“What I don’t understand is people who claim to agree with him, but don’t repent and live a cruelty-free life.”

Bryan, I am one of those people so I can shed some light on this. The reason I continue eating meat, while strongly agreeing with Mike and disagreeing with you, is that ……. spoilers ahead…..

.

.

.

.

.

…it is not the eating per se that is unjust. Only the killing is. But I am not the one who killed the animal. If I had to kill it myself, of course I would not do it, because it is *unjust*, and therefore I would stop eating meat. (with the exception of killing animals who are aggressors and actually attack me)

In order to stop eating meat, I guess you need to believe in some kind of complicity theory, but I don’t believe in it. (for example, I believe if I pay you to kill somebody, and you kill him, only you have committed a crime, I did not).

Maurizio

Oct 27 2016 at 3:13pm

Also, Bryan, I will go out on a limb and suggest that, if you had to kill the cow or the pig yourself, you would instantly realize Mike is right. And what’s more, the difference between killing and eating would suddenly be so obvious that you would wonder how you could abstract it away.

James

Oct 27 2016 at 9:13pm

Let me get this straight:

Huemer says that while the badness of bug pain and cow pain differ in type, the badness of cow pain and human pain differ in degree. Caplan says that while the badness of bug pain and cow pain differ in degree, the badness of cow pain and human pain differ in type. And they were actually expecting to resolve this by arguments premised on intuitions.

The most useful outcome of this discussion would be a reassessment of the proper scope of usefulness of moral intuitions e.g. maybe human intuition is not useful for moral questions when not all of the affected parties are human.

Justin

Oct 27 2016 at 10:25pm

Pain has great evolutionary value. So why wouldn’t bugs feel pain?

If all biology is reducible to chemistry, then I’m not sure how pain has any evolutionary value for any organism. Certain stimuli will necessarily produce a particular response, just as any simple chemical reaction will produce one particular outcome rather than others. The feeling of pain per se doesn’t drive the response.

On this understanding, pain is a useless bummer, an epiphenomenal side effect conscious creatures suffer.

It’s all an academic question anyway as morality itself goes out the window under this assumption, as objective morality is an illusion in a world without agents able to freely choose one action vs. another. Why eat meat and indirectly cause animals to suffer? The answer is merely that there is a complex series of chemical reactions which ultimately result in me consuming an animal’s flesh. Is there an “I” which can control the chemical reactions?

entirelyuseless

Oct 27 2016 at 10:47pm

Miguel:

I’m not sure what you thought was circular. I was not attempting to prove that people care especially about humans. I think it is obvious — people care about humans because they are human, and they care less about other animals because they are not. That is perfectly obvious from e.g. the cases people mention like babies and mentally deficient people and so on. They are not measuring IQ: they are deciding whether something is a human. And it is quite evident that there are extremely good evolutionary reasons for doing this.

Chip Smith

Oct 28 2016 at 12:25am

Pain has great evolutionary value. So why wouldn’t bugs feel pain?

I take this question more seriously than most. I think it’s genuinely important and worthy of further investigation, but I think the evolutionary premise that Bryan posits is inaccurate. What evolution favors is not pain as such, but reaction, or irritability that advances an organism’s survival. There are highly plausible, if not incontrovertibly proven, neuro-anatomical reasons why bugs might exhibit responsive behaviors that we perceive as pain but that do not register subjectively to the organism as pain. You needn’t wade far into the relevant literature to encounter this conclusion, and I’m pretty sure it’s close to the consensus view among disinterested researchers.

So while I don’t want to dismiss the reductio out of hand, I think the leap to factory farms, based on our present knowledge, is beyond dubious, and I frankly think it’s disingenuous.

If it were to be shown that bugs do experience pain of some qualitative valence that warrants moral consideration, then we should begin to consider this fact in earnest and modify our behaviors accordingly. Yes, it would be difficult. There would be bullet-biting and trade-offs and we might question the harmony of the universe in turn. So be it, I’d say.

But let’s be clear about false equivalence. Bugs are crushed and rended and devoured as a matter of natural course, and no one is talking about caging and breeding them, or injecting them with chemicals, or making them suffer for the sole purpose of satisfying a dietary itch that can be slaked through other means. Yet that’s exactly what we’re talking about when we attempt to justify the treatment of more neuro-anatomically complex animals in slaughterhouses — and there’s little question (as a matter of consensus) that pigs and cows and even birds, do experience some, possibly profound, order of pain, and that a vast and easily avoidable measure of such pain is caused not incidentally (as with bugs) but intentionally by humans, and for reasons that reduce to appetite, convenience, and whim.

This is, at least prospectively, a troubling and even abominable situation. It behooves those who take moral questions seriously to at least investigate the facts of factory farming with open eyes. If there’s a case where the precautionary principle is counseled, I think this is it. Veganism turns out to be absurdly easy in the modern world, and less extreme options also mitigate against prospective (and likely) animal suffering.

This needn’t have anything to do with animal “rights” (a bit of a herring, IMO); rather it can, and probably should, be apprehended in terms of minimal animal welfare, or just plain human decency.

Maurizio

Oct 28 2016 at 3:59am

“pain has evolutionary value.”

Actually, as of today we have no explanation for the evolutionary value of consciousness. If we were robots with no consciousness, everything would work exactly the same. (and would appear indistinguishable to the viewer).

mico

Oct 28 2016 at 7:49am

Morality isn’t a transcendental concept, it’s just an evolved trait. Humans don’t like killing other humans because that is necessary for complex cooperative societies. Since complex cooperative societies are better at war and reproduction, people capable of organising into such societies conquered and outbred those who weren’t.

Conversely humans don’t get any big advantage from disliking killing bears or insects which is why we don’t see that as intrinsically immoral. Some people get bears and insects confused with humans, but then some people can’t read. Some people are broken.

If vastly superior aliens came along and didn’t value human life then their morality would probably replace ours in much the same way.

James

Oct 28 2016 at 8:29am

Chip Smith,

Vegans talks so much about farms raising pigs and cows and chickens that you can be excused for thinking those are the only animals being raised to eat. However, there are farms raising all kinds of insects for purposes of human consumption. It is more common in developing nations but it goes on around the world. If we define “bugs” to include some crustaceans, then it’s a pretty common occurrence in the US.

Benjamin R Kennedy

Oct 28 2016 at 9:22am

Anthropomorphism is a useful survival adaptation – if we can interpret animals as rational human-like agents (despite their total lack of consciousness), we can better navigate our environment by doing things like hunting animals, not being hunted by other animals, and domesticating them to our advantage

Benjamin R Kennedy

Oct 28 2016 at 9:26am

Bryan, what if someone had convinced your parents that animal pain was morally important. If you are being honest, is it not highly likely that this belief would have been passed on to you? And if so, how can you possibly distinguish true moral importance from that simply imparted by your parents?

Dustin

Oct 28 2016 at 11:38am

Q1: Does ‘thing’ consciously care if I kill it?

If Q1 = Yes -> it is immoral to kill ‘thing’

If Q1 = No -> Q2: does any ‘other thing’ love ‘thing’ and therefore care if I kill ‘thing?

If Q2 = Yes -> it is immoral to kill ‘thing’

If Q2 = No -> it is not immoral to kill ‘thing’

This framework applies to aliens, bugs, centaurs, humanoids, robots, clingons, etc…

austrartsua

Oct 28 2016 at 12:02pm

@dustin, a fine schematic. But do animals consciously care about anything? Or are they just like robots, programmed by instinct to behave in certain ways? Does my roomba care about being at full charge? Or is it only that we anthropomorphize them and convince ourselves that they have higher thoughts? We are notoriously bad at this with our pets. Cats and dogs don’t think about anything! They are just good at convincing us that they have these complex inner lives and are worthy of our protection. We are suckers for them.

austrartsua

Oct 28 2016 at 12:05pm

I’ve never heard an animal rights activist come up with a good explanation for what we should do about the jungle. The jungle is a horrible place. Billions of animals go through days and nights of suffering, hunger, loneliness, far worse than a factory farm, all the time. What does Peter Singer say about such grotesque horror? Should we flatten the amazon and replace it with a petting zoo? Such observations reveal the absurdity of “animal rights”.

Dustin

Oct 28 2016 at 12:30pm

@austrartusa

‘care about’ was imprecise, and I agree with your general statement. Grieve, or some similar term, would be more appropriate. For example, we do know that certain animals grieve the loss of their kin. We also know that some animals are self-aware; if a self-aware animal has not taken its own life, we can presume it prefers life to death.

Application of this framework: If I maintain an ant colony, I would care about and grieve their destruction. Therefore Bryan should not exterminate my ants, even if they are stupid.

Maurizio

Oct 28 2016 at 12:37pm

@austrartsua

“I’ve never heard an animal rights activist come up with a good explanation for what we should do about the jungle. The jungle is a horrible place.”

Should we do something about the people in Libya who kill each other? I don’t see why someone couldn’t honestly respond “no” to this question, while at the same time believing killing people is wrong.

Same thing for the jungle.

mico

Oct 28 2016 at 7:28pm

“Anthropomorphism is a useful survival adaptation – if we can interpret animals as rational human-like agents (despite their total lack of consciousness), we can better navigate our environment by doing things like hunting animals, not being hunted by other animals, and domesticating them to our advantage”

No we can’t because animals aren’t like humans in important ways. They aren’t rational human-like agents. Seeing animals as people is maladaptive, like having Downs Syndrome.

Benjamin R Kennedy

Oct 29 2016 at 1:30pm

That fact that it almost a completely universal trait suggests otherwise. It’s also not “seeing animals as people”, because nobody actually mistakes a dog for for human. Rather, it is the attribution of human characteristics to animals, not a denial of their animal nature. Since humans are also a type of animal, trying to understand animal behavior via human behavior is a pretty good starting point. Something as simple as believing “that lion is hungry and wants to eat me” is useful anthropomorphism – lions are not rational agents that “want” anything

pgbh

Oct 29 2016 at 11:04pm

Bryan,

Isn’t it pretty obvious that your espoused ethical theory is completely ad hoc?

Your intuition is that killing humans is bad, but killing houseflies isn’t bad. So you’ve come up with some sort of meta-ethical theory to retrospectively justify those intuitions.

Of course, the intuitions themselves are not based on any sort of abstract “theory”. They are based on the fact that as a human, you have naturally evolved to find other humans more interesting than, say, cockroaches.

The result is that the theory doesn’t really make any sense. It’s like trying to play connect-the-dots with the output of a random number generator.

Give Huemer some credit. He’s interested in coming up with a meta-ethical theory that seems reasonably plausible, which is why he won’t buy into your views.

If you won’t agree with him, you should at least come out and say “My moral views aren’t based on any sort of logical schema, but I won’t change them. So we’ll just have to disagree.”

pgbh

Oct 29 2016 at 11:34pm

David Condon,

No, Bryan did not say that.

What he said is that, in his view, moral value depends to some extent on IQ. This is not at all the same as saying that low-IQ humans have low or zero moral value.

In general, you cannot trap Bryan by claiming that some meta-ethical theory he propounds has some sort of negative implication. This is because Bryan’s ethical theory really boils down to “do whatever my intuitions tell me to be right.”

Therefore, you can never say “You claim that we should always follow principle X, but doing so would have [bad] consequence Y. Therefore your theory is refuted.”

This is because “Bryan-ethics” is not based on any sort of widely applicable principles to begin with. Hence he can always just respond “Actually, we shouldn’t follow principle X in that case.” This makes Bryan’s personal philosophy more or less impossible to refute. All you can do is disagree with his intuitions.

However, it also makes it completely useless with regard to the main project of meta-ethics, which is to agree on principles which can be applied in cases where people’s intuitions are conflicting or absent.

So if you’re looking for a solid meta-ethical theory, it might be best to look elsewhere. Of course, people have been trying to come up with one for 2500 years and it hasn’t happened yet.

pyroseed13

Oct 30 2016 at 11:35pm

A lot of the commenters here are missing Bryan’s point. “But if it’s ok to kill animals because they have low IQs and can’t communicate, then should we kill my grandmother with Alzheimers, person with Down syndrome, etc.” Obviously not, because as Bryan has pointed out, the gap between the average person and a person with a severe intellectual disability is vastly smaller than the gap between the average person and a cow. Furthermore, animals do not have an ability to hold preferences, so no one really knows if animals would prefer to roam freely rather than be confined to these supposedly cruel factory farm conditions.

Maurizio

Oct 31 2016 at 3:50am

@pyroseed13

There are clearly people who have fewer cognitive abilities than dogs and pigs.

Animals do have ability to hold preferences. The fact they scream and try to escape when you try to slaughter them *proves* they would *prefer* to roam freely. Also, present a dog with a choice (e.g. one plate to the right and one plate to the left) and the dog will make the choice, according to his preference.

pyroseed13

Oct 31 2016 at 9:23am

@Maurizio

“There are clearly people who have fewer cognitive abilities than dogs and pigs.”

But you wouldn’t say, therefore, that a dog is closer to the average person than a person with intellectual disabilities, which is the point I was making.

“Animals do have ability to hold preferences. The fact they scream and try to escape when you try to slaughter them *proves* they would *prefer* to roam freely.”

Sure, as others have detailed, animals react when they appear threatened. But how does anyone know whether animals prefer cages, crowded factory farm conditions, or roaming freely? It just amounts to people imposing their own preferences on animals e.g. “I wouldn’t want to live in those conditions so the animals must hate it.”

Benjamin R Kennedy

Oct 31 2016 at 10:20am

Non-human animals do not have preferences – you are anthropomorphizing. Suppose I made a robot with a wheels and a heat sensor, and I uploaded a program that was “keep roaming, but avoid anything hot”. You could, in a very generic sense, say the robot “prefers” cold to hot, but this is very, very different from human preferences. Human preferences are intelligent and self-aware – we are aware of the fact we are making decisions. As far as we know, animal preferences are like robot preferences – they are not aware of a decision-making process.

More complicated animals may be different – I recently saw a gorilla at a zoo that absolutely seemed like it was pondering the meaning of life itself. But I may have also been anthropomorphizing at the time.

Comments are closed.