Irvine is a master planned community in Orange County, California, with a population of just over 300,000. It is one of the few areas of coastal California where home building is still quite robust, perhaps due to the influence of the Irvine Company.

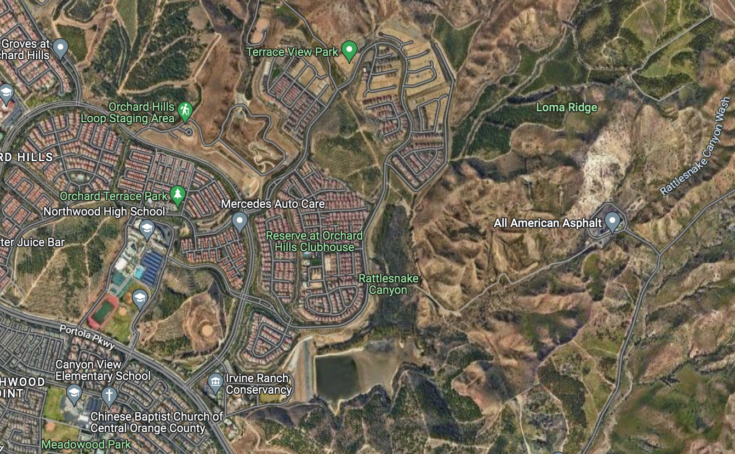

A recent article in the Orange County Register provides a good example of Coasean economics in action. Recent growth in Irvine has pushed new housing construction ever closer to an asphalt manufacturing plant. (New housing construction is in the upper center of map below, the asphalt plant is on the right):

This led to an “externality problem”:

Odors from the plant are particularly strong in the nights and early mornings, Lien said. Every night, he checks his hood ventilation and laundry room ventilation systems to ensure odors won’t seep through.

“We basically keep our house shut. It’s all sealed, and (we) never open windows,” Lien said.

Due to the large number of homeowners, it is difficult to negotiate a satisfactory solution to this problem. But this case was special in several respects. First, real estate development is extremely profitable in Irvine, if you can find available land. In addition, the Irvine Company plays such a major role in Irvine that it needs to maintain a good relationship with the city.

In the end, the plant was sold to the Irvine Company for $285 million. I’m not expert on asphalt plants, but that seems like a huge sum of money for such a modest sized facility (see picture in the article). The article suggests that the owners had no interest in selling, and only did so because they reached very favorable terms:

“All American Asphalt plant was not interested in selling, and they are only selling right now because we’ve been able to reach a price that they feel is commensurate with the long-term profits that the asphalt plant would have generated,” said Chi.

I suspect that “commensurate” is an understatement, as they knew they were in a strong negotiating position. Of course, the value of land in places like Orange County is strongly dependent on whether the local government will grant permission to build new homes. As part of the deal, the city of Irvine will allow the Irvine Company to develop a modest portion of the land.

The funding for the purchase of the plant is set to come from a “concurrent deal” the city made with Irvine Company. In the deal, the Irvine Company will give the city approximately 475 acres of land, with about 80 acres (worth around $330 million, according to city documents) allocated for housing development.

For you land developers in Oklahoma City, that’s not a typo. In Irvine, 80 acres of buildable land is worth $330 million. (BTW, I believe that some of the 475 acres being donated for parkland is extremely hilly land, which is difficult to develop.)

This example illustrates the complexity of the Coase Theorem. In some cases, negotiation among the parties leads to a free market resolution of externalities. In other cases, regulation might be required due to the existence of “transactions costs.” Master planned communities make it easier to overcome the problem of externalities, which is one reason why Irvine allows more new construction than do other Orange County communities.

In this case there are several externalities lurking in the background, which impacted the final result. In addition to the bad smell, Irvine residents worry about traffic congestion. As a result, they are not always happy to see new development. The Irvine Company (implicitly) struck a deal with the city that will eliminate the bad smell problem while slightly worsening the (less severe) traffic issue. This overcomes the normal “public choice” problem by turning nearby homeowners from being the most opposed to new development to the most supportive of new development.

NIMBY policies impose external costs on an even more invisible group—people that would like to live in Irvine but cannot afford to purchase a house in the city. That’s a more difficult problem to solve. In recent years, the state government in California has been pushing local governments to allow more housing construction. Almost everyone wants more housing—but somewhere else.

READER COMMENTS

Aaron M.

Apr 27 2023 at 2:03pm

You seem to suggest that the bad smell is an externality. However, I don’t think that it is. In the Orange County Register article you link to, it says:

“The plant has been open since the early 1990s and predates development in Irvine’s northern area.”

Based on this, the bad smells are not an externality, as the homeowners and land developers were aware of this cost when building and purchasing their homes. This cost was already incorporated into the purchase price of the land and the homes.

In the end, the use of the master planned communities appears to be a way to of addressing a market failure due to transaction costs. However, this is different from an externality. Right?

vince

Apr 27 2023 at 4:33pm

If the company emits a foul odor beyond the limits of its property, wouldn’t that be an externality?

Scott Sumner

Apr 28 2023 at 12:21pm

Perhaps there is ambiguity about the meaning of the term “externality”. Does it refer merely to costs imposed by the asphalt plant on neighboring homeowners, or does it mean market failure?

robc

Apr 28 2023 at 6:19pm

Exactly. And you used it correctly. It is an externality regardless of any other considerations.

Thomas Hutcheson

Apr 28 2023 at 4:54pm

Whether it is an externality does not depend on when the external effect was discovered. The value of the externality could change, however.

Thomas Hutcheson

Apr 27 2023 at 5:30pm

True, but NIMBY policies also impose costs on the beneficiaries of the city services that revenue from new development would bring. Nimby is often just a problem of no way to compensate those who suffer from hyper-local negative externalities out of the surplus from liberalized land use policies that benefit “everybody.” The political economy problem of concentrated costs and dispersed benefits that bedevils trade policy reform.

Scott Sumner

Apr 28 2023 at 12:22pm

I agree.

David Seltzer

Apr 27 2023 at 5:39pm

Scott: on a much smaller scale, a friend who lives in a high-net worth gated community, regularly complained about a neighbor who drove a 2010 Honda. His neighbor had the temerity and outsized chutzpa to park next to my friend’s Bentley at the community golf course parking lot. he seemed really vexed by this “problem.” I said, there is a simple solution. Offer him enough for the car so that both of you get what you want. He did so and problem solved.

vince

Apr 27 2023 at 6:39pm

It looks like the Irvine Co donated land to the City, and the City purchased the Asphalt Co for $285 million to shut it down. For the donation, Irvine Co gets to continue developing in the area? That stinks like asphalt.

Why didn’t Irvine Co just buy the Asphalt plant directly?

Scott Sumner

Apr 28 2023 at 12:16pm

I suspect that they first wanted a guarantee that they would be able to build new housing in that area.

nobody.really

Apr 28 2023 at 6:15am

The growth of the US south and southwest—and the rise of these regions as political powers—owes much to the invention of air conditioning. By the late 1960s, the invention of central air conditioning was triggering booming demand for housing throughout the south—including in the (previously) small town of Sun City, AZ. Housing development, especially for retirees, had become one of Arizona’s primary industries.

Alas, Sun City adjoined an enormous feedlot, which stank and generated flies. This was impeding further housing development, and arguably posed a health hazard to people living in proximity to the feedlot—in legal terms, a nuisance. But the feedlot predated most of the housing development; under Arizona law, it might be possible to force a nuisance to cease and desist—but people who were “coming to the nuisance” would not be entitled to that remedy. The developer sued to shut down the feedlot. What outcome?

In Spur Industries v. Del E. Webb Development Co., 108 Ariz. 178, 494 P.2d 700 (1972), the Arizona Supreme Court distinguished between private nuisance and public nuisance, which included any “place in populous areas which constitutes a breeding place for flies . . . ” and other animals that can carry disease. Because the feedlot qualified as a public nuisance, the court upheld an injunction forcing the lot to close (or relocate). But given the equities, the court ordered the developer to compensate the feedlot owner, and remanded the case to a lower court to determine the appropriate compensation.

In short, we arrived at a similar remedy to the situation in Irving, CA, but mandated by a court rather than arrived at by private negotiation.

David S

Apr 28 2023 at 11:32am

I wonder how the impending closure of the plant will impact asphalt prices in Irvine and surrounding towns. My guess is that costs for small projects in the Irvine/Orange County/Huntington Beach area will go up because travel distances from remaining plants will increase. So it goes–it will make costlier substitutes more attractive options–paving block, concrete, monorails, etc…

robc

Apr 28 2023 at 6:23pm

This reminds me of a similar situation in Louisville KY. At the end of market street, is the Butchertown neighborhood. It got its name for obvious reasons, the animals would be sent from the market down the street to meet their end.

One Butcher remains (or remained, I left Louisville a decade ago). The area was gentrifying and the new residents complained about the smell. I thought they were pretty stupid, the neighborhood didn’t try to hide anything, it was right there in the name.

I should check to see if it still exists.

robc

Apr 28 2023 at 6:26pm

JBS Pork Production Facility. So I guess it is still there.

Scott K

Apr 28 2023 at 8:47pm

One key component of this deal that’s not being discussed is that the City, NOT the Irvine Company, is taking ownership – and critically, responsibility for, all the cleanup and liabilities associated with the asphalt site.

Irvine is better positioned to deal with those risks and costs over a longer timeframe than the developer, who has an extremely cozy and profitable history with Irvine and other cities reliant on periodic land grants and development deal related tax base expansion. It’s a win-win for the two principal parties and surrounding homeowners, but does nothing for creation of affordable housing IMHO.

Comments are closed.