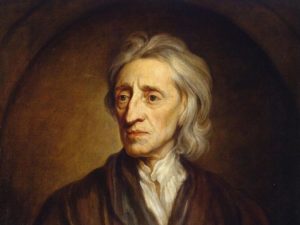

John Locke: Mercantilist?

By Amy Willis

Let’s look at some passages from “Some Considerations” [SC] that most support the claim that Locke was a mercantilist and then some passages in which Locke seems to distance himself from mercantilism. My suggestion is that the first group of passages show that Locke subscribed to the view that exports of consumable goods should exceed imports while the second group of passages show that Locke subscribed to the view that ultimately the riches of a nation does not consist in its stock of silver or gold. Rather, the wealth of a nation consists in the amount of the conveniences that are enjoyed by its inhabitants. Locke was a mercantilist in the sense of favoring an excess of exports of consumable commodities over imports of consumable commodities. But he was not a mercantilist in the sense of taking a nation’s wealth to consist in the magnitude of its stock of silver and good.3 In addition, we will see that Locke’s mercantilist view that international trade is a zero-sum game contravenes his own general recognition of the positive-sum character of all voluntary economic exchange.’

Locke writes that “… our growing rich or poor depends… only [on] which is greater or less, our importation or exportation of consumable commodities.” (SC 15) He contrasts two cases in which England annually exports two million pounds of consumable goods. In one case, England imports one million pounds of goods which it consumes and one million pounds of silver or gold coins. In the other case, England imports two million pounds of goods all of which it consumes. Locke says that England prospers in the first case, but not in the second. If more consumable goods are imported than are exported, “our money must go out to pay them, and we grow poorer.” (SC 15)

Locke contrasts three scenarios involving a farmer who sells 1000 pounds of commodities a year. In one case, the farmer spends only 900 pounds per year on consumable goods and “he grows every year a hundred pounds richer.” (SC 19) In another case, the farmer only spends 500 pounds per year. In this case, “the owner[is] a better husband” and will be “so much richer.” (SC 19-20) In the third case, the prudent farmer dies and leaves the farm to his spendthrift son who spends 1100 pounds per year and, hence, his household becomes poorer (and more debauched, idle, and quarrelsome) every year. (SC 20) The lesson is that, if England is to prosper, it must spend only a portion of what it earns in trade. “[M]oney is brought into England by nothing but spending here less of foreign commodities, than what we carry to market can pay for.” (SC 20) Locke tells us that, “We have seen how riches and money are got, kept or lost, in any country” and that is, by consuming less of foreign commodities, than what by commodities, or labour, is paid for.” (SC 21)

Locke criticizes legislation that caps interest payments below their “natural” level. He says that such legislation may affect “the distribution of the money we have amongst us Englishmen here at home.” But such legislation “would be of no advantage to the kingdom.” In contrast, sensible legislation “brings in more [money] from abroad” (SC 62) and, hence, advances the kingdom’s wealth. Indeed, legislation should facilitate foreigners purchasing land held by English proprietors. For,

- … whatever a foreigner who purchases land here, gives for it is so much every farthing clear gain to the nation: for that money comes clear in, without carrying out any thing for it, and is every farthing of it as perfect a gain to the nation, as if it dropped down from the clouds. (SC 63)

Still, despite these passages, it is not at all clear that Locke holds to the mercantilist view that wealth (or riches) consists in the possession of money. Indeed, Locke tells us that, “Gold and silver, though they serve for a few, yet they command all the conveniences of life, and therefore in a plenty of them consist riches.” (SC 12) Indeed,

- Riches do not consist in having more gold and silver, but in having more in proportion than the rest of the world, or than our neighbors, whereby we are enabled to procure to ourselves a greater plenty of the conveniences of life, than comes within the reach of neighboring kingdoms, and states… (SC 13)

Although each nation should seek a disproportionate quantity of silver and gold, the reason for doing this is that a disproportionately large share will “procure… a greater plenty of the conveniences of life” for the nation.

Locke endorses legislation that “draw[s] more money into England.” (SC 62) However, Locke’s case for such legislation is that this increase of money will enable landholders to “sell better, and yield a higher price” for agricultural products and this benefit will compensate landholders for bearing through taxes on land “the greatest part of the burden of the kingdom.” (SC 62)

How can England acquire such a surplus of silver and gold? According to Locke,

- In a country not furnished with [silver or gold] mines, there are but two ways of growing rich, either conquest or commerce. By the first the Romans made themselves master of the riches of the world; but I think that, in our present circumstances, nobody is vain enough to entertain a thought of our reaping profits of the world with our swords, and making the spoil and tribute of vanquished nations the fund for the supply of the charges of the government, with an overplus for the wants, and equally-craving luxury, and fashionable vanity of the people. (SC 13)

The only reliable route to England having silver and gold in greater proportion than the rest of the world is commerce. Here Locke at least comes close to disavowing the common mercantilist view that a major reason for governments maintaining “a sufficient quantity of hard currency” was “to support a military that would deter attacks by other countries and aid its own territorial expansion.”5

How does such an addition to a nation’s stock of money yield a greater quantity of the conveniences of life for inhabitants of that nation? Locke holds that a nation having a large stock of money has value for that nation because of the propensity of that stock to support and extend trade within that nation and, in that way, to enhance the conveniences of life in that nation. He tells us that, while “it matters not, so it be here amongst us, whether the money be in Thomas, or Richard’s hands,” that money will serve the wealth of the nation, “provided it be so ordered, that whoever has it may be encouraged to let it go into the current of trade, for the improvement of the general stock and wealth of the nation.” (SC 62, emphasis added)

Here Locke is relying upon his idea that a certain amount of money needs to be in circulation (at a certain velocity) within a nation for a certain level of mutually beneficial domestic trade to be sustained or exceeded. Locke also seems to presume that a sufficiency of money to maintain or extend domestic trade requires a surplus of money accruing to the nation from its international trade. According to Locke, it had been through “this over-balance of trade” with Spain” that “the greatest part of [England’s] money hath been brought to England, out of Spain. (SC 18)

It is crucial to note that England could not move toward a disproportionately large share of the world’s money without moving Spain toward a disproportionately small share. On Locke’s mercantilist view about what counts as a gain and what counts as a loss in international trade, viz., increases and decreases of silver or gold, international trade is a zero-sum game. England’s enrichment requires Spain’s impoverishment. In fact, Locke feels a need to justify England’s imposing this loss on Spain. He tells us that “riches are only for the industrious and frugal” and the Spanish are “lazy and indigent people.” (SC 72)

In contrast, Locke clearly thinks that the domestic trade is positive-sum. In “Some Considerations,” Locke is especially concerned to vindicate a borrower’s payment of interest to lenders in voluntary exchange for the borrower’s use of the lender’s money. This vindication underwrites Locke’s case against state-mandated interest rates. Locke’s specific strategy for vindicating interest payments to owners of money in exchange for the borrower’s right to use the owner’s money is to show that such exchanges are entirely parallel to rental payments to owners of land in exchange for the renter’s use of that land. On one level, Locke simply presumes that his readers will favor landowners and renters being allowed to enter into leasing arrangements and will reject out of hand rents being set by legislation. Showing the parallels between renting land and borrowing money should convince these readers to favor allowing the rental of money and to disfavor legislative setting of rates of interest.

Nevertheless, Locke reinforces this argument by explaining why both the voluntary rental of land and the voluntary borrowing of money will be mutually advantageous to the parties involved. The essential—albeit, not quite explicit—explanation is that renters will rent, and borrowers will borrow if and only if they can put the land or money in question to sufficiently more productive use than the land or money would be put to by its owner. The land or the money will be sufficiently more productively used by the renter or the borrower if and only if the use of the land under the lease or the money under the loan yields enough income to the renter or the borrower both to pay for the lease or loan—thus, benefiting the owner of the land or the money—and to provide a sufficiently attractive net gain to the renter or the borrower. In effect, each sort of economic interaction moves a resource to a more productive use and because the interaction is voluntary the economic gains from this move are divided between the resource owner and the resource user in a way that leaves each a net beneficiary. (SC 36-37)

Part of my reason for explicating this argument from “Some Considerations” is to point to a tension between this Lockean gains-from-trade argument and Locke’s own mercantilist commitment to the zero-sum character of international trade. Central to Locke’s discussion of the mutual advantages that accrue to landowners and leasers and to money owners and borrowers is the idea that voluntary exchanges strongly tend to be mutually advantageous. These interactions would not take place except for each party’s belief that he or she will on net gain.

Similarly, if we think of international trade, as Locke tends to, as trade between nations, rather than as trade between private parties from different nations, we should expect voluntary commercial interaction between nations to be mutually advantageous. If each party to any given international exchange did not judge the interaction to be on net beneficial to it, the exchange would not take place. Suppose, as Locke and mercantilists in general, did that sometimes a nation needs to increase the quantity of hard currency in circulation within it. If the need for such an increase in hard currency is to be met through commerce, this nation will have to export more consumable goods to other nations than it imports from them. But no other nation will voluntarily agree to any commercial interaction that will diminish its stock of hard currency unless it sees that interaction as being on net advantageous to it—presumably by adding enough to its supply of consumable commodities to compensate for its loss of hard currency.

For more on these topics, see

- Mercantilisim, by Laura LaHaye. Concise Encyclopedia of Economics.

- “Mercantilism Lives,” by Charles L. Hooper. Library of Economics and Liberty, Apr. 4, 2011.

Peter Berkowitz on Locke, Liberty, and Liberalism. EconTalk.

Peter Berkowitz on Locke, Liberty, and Liberalism. EconTalk.

So, Locke should conclude that in the ordinary course of affairs, any voluntary international exchange that advantages one trading nation will also, contrary to mercantilist doctrine, benefit its trading partner. Were Locke to apply his insights about voluntary domestic trade to international trade, he would have been even less of a mercantilist than he was.

Footnotes

[1] The Collected Works of John Locke, volume 8; henceforth SC.

[2] See David Henderson’s Concise Encyclopedia biography of John Locke.

[3] In her John Locke: Economist and Social Scientist, Karen Vaughn maintains that it is the systematic character of Locke’s economic thought that distinguishes him from the mercantilists.

[4] Laura LaHaye, “Mercantilism.” Concise Encyclopedia of Economics.

* Eric Mack is a professor of philosophy at Tulane University. You can find more of his writing in the Online Library of Liberty.