Over the past year, the US has been hit by a pretty severe labor supply shock. Employment is sharply depressed, but wages are rising fast and companies are having trouble finding workers. At this point the question is not whether a labor supply shock exists, rather the issue is what is causing labor supply to be so depressed. I’ve seen at least three theories:

1. A supplemental unemployment insurance program that pays lower wage workers more than they earned on their previous jobs.

2. Lack of childcare, partly due to school closures.

3. Fear of the health risk associated with working.

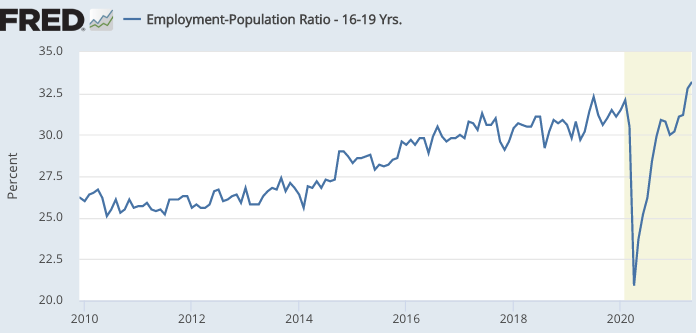

In order to evaluate those theories, let’s look at some employment data. Unfortunately, while I found employment/population ratios for three age groups, for 20-24 year olds I had to rely on total employment data. Let’s start with teenagers:

Teen employment is at the highest level since the Great Recession, even higher than the extremely strong labor market of 2019. Given the current state of the labor market, that’s actually pretty amazing. (Yes, the employment ratio is far below the levels of the 20th century, but teens were far more likely to work in the old days.)

So there’s little evidence of a negative labor supply shock for teens. To be sure, the supply curve for teens may have shifted slightly to the left, and that effect could have been offset by moving up and to the right along the curve due to higher wage rates. Even so, the teen data really stands out when compared to other age groups.

Unfortunately, the high teen rate of employment is consistent with all three theories discussed above. They typically have not been receiving UI, they typically don’t have child care issues, and they are at relatively low risk from Covid. So let’s look at three other age groups:

My first reaction is that fear of getting Covid is not the whole story. The difference between employment levels for teens vs. 20-24 year olds is pretty shocking. Teen employment is higher than during the 2019 boom, whereas employment of workers just a few years older is still severely depressed. Obviously there is very little difference between the health risk for teens and young adults. In both cases, the risk is pretty low. That means the very strong employment ratio for teens is likely due to either the fact that they typically do not received UI or the fact that they don’t need child care.

All three of the adult age groups show significant declines in employment. In percentage terms (not percentage points terms) the decline is largest for old people, somewhat less for young workers, and even less for middle age people. And yet unless I’m mistaken, childcare issues are most important for middle age people.

I am especially struck by the fact that employment for 20-24 year olds seems to have declined more sharply than for 25-54 year olds. They experience less health risk than 25-54 year olds, and they probably have less need for childcare. On the other hand, 20-24 year olds tend to be lower wage workers, the group most likely to earn more on unemployment insurance than on their former jobs.

While I suspect that all three factors are depressing labor supply, the strongest evidence seems to be for the effect of the supplemental UI program.

Labor supply shocks make things difficult for policymakers, especially policymakers that focus on the employment part of the Fed’s dual mandate. In 1974, the US experienced a negative labor supply shock, and this contributed heavily to a “supply-shock” recession. The longer this supply shock lasts, the more likely that it will trigger an outcome similar to 1974.

To be sure, the 1974 labor supply shock had completely different causes—the removal of the Nixon wage controls:

Nonetheless, a labor supply shock has a contractionary impact on the economy, regardless of the cause. Thus far, the effect is not to cause a recession, rather it is merely slowing the recovery from a recession. But there is a risk that this problem could confuse monetary policymakers and lead to an overshoot of inflation. Yes, the Fed wants to see a mild overshoot of inflation, but a major overshoot would lead to subsequent tightening (as the Fed needs to hit its 2% average inflation target.)

As always, the Fed needs to avoid targeting real variables such as employment. That’s where they got in trouble during the late 1960s and 1970s. Phillips Curve thinking also contributed to the inflation undershoot during the late 2010s. Stick to nominal targets.

READER COMMENTS

Physecon

Jun 5 2021 at 3:54pm

I’m not following this. Shouldn’t quantity supplied goes up with higher prices? I also don’t recall price ceilings leading to shifts in supply or demand curves (at least on short to medium time horizons)

Scott Sumner

Jun 5 2021 at 6:17pm

After the controls were removed, workers demanded higher wages. This shifted labor supply to the left.

Physecon

Jun 6 2021 at 2:48am

The same workers?? This sounds like an argument for rent control

Andrew_FL

Jun 6 2021 at 9:04am

I had the same question as you a few years ago the last time I remember Scott saying this, but what I think he may have in mind is that in 1974 unions had much more power over labor markets than they do today.

Scott Sumner

Jun 6 2021 at 12:01pm

The wage controls were not strict enough to create a labor shortage, given the fact that labor markets are not perfectly competitive and the controls lasted just a few years.

Frank

Jun 6 2021 at 9:48pm

Do you mean that the wage controls didn’t bind?

Scott Sumner

Jun 7 2021 at 12:15pm

No, they were binding. But the effect of a binding constraint is different when markets are not perfectly competitive.

Frank

Jun 7 2021 at 12:24pm

Then on efficiency grounds, the wage controls should have been left in place, as they give higher employment and higher wages. 🙂

Scott Sumner

Jun 7 2021 at 2:51pm

The wage controls were maximums, not minimums. And the negative effects get worse in the long run, as markets are more competitive in the long run than in the short run.

Frank

Jun 5 2021 at 9:26pm

With labor demand and supply functions of the real wage, as they truly are, no curves shift. We just move toward equilibrium from wherever the wage-price controls bound, presumably below the equilibrium.

[One can draw the curves against the nominal wage, but P then determines the position of the curves. Then both shift all over the place when w and P are freed. No way to know that w must rise more than P from that diagram. But it is true plotting against the real wage, w/P, that wages must rise more than prices. ]

Thus, it’s misleading to call the episode a supply shock. It’s a removal of a regulatory shock. 🙂

Scott Sumner

Jun 6 2021 at 12:02pm

Fair point, but the macro effects are similar to a negative supply shock.

Frank

Jun 6 2021 at 1:53pm

With the nominal wage on the Y axis, it’s a supply plus a demand shock.

Daniel Hill

Jun 5 2021 at 4:33pm

Scott, can you access a breakdown by gender for the 25-54 age group?

If childcare is an issue, given dominant social norms over who stays home to mind the kids, you would expect to see a slower bounce back of female participation rates than for males…

Scott Sumner

Jun 5 2021 at 6:21pm

Good point. It looks to me like the declines for each gender are quite similar, but I’m not certain:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/categories/32445

John Brennan

Jun 6 2021 at 2:09pm

Great post. When I added the men to the women, it looks like the women recovered to a slightly higher level. The UI intervention seems to be the culprit–as you point out. The early to mid-20’s is usually a time of “learning the ropes” to “putting in the time” to gain advancement (not the greatest time during the career ladder process). The UI intervention seems to have interrupted that with, in some cases, better than free money (leisure time too). Alternatively, post college student hiring may have delayed slightly–for several possible reasons–and will pick up in the coming months.

Thomas Lee Hutcheson

Jun 5 2021 at 6:17pm

You my think it is unfortunate, but targeting full employment of labor is part of the Fed’s mandate.

I think it would be better if the target were full employment of all resources, not just labor, which is how I see NGDP targeting. The Fed’s utility function real income and prices (increasing at the optimal rate given the stickiness of nominal wades and the size of expected supply shocks) with a one-for-one tradeoff.

Scott Sumner

Jun 6 2021 at 12:03pm

No, the Fed does not have a mandate to target employment. They have a mandate to produce high employment. The best way to do that is to NOT target employment.

Thomas Lee Hutcheson

Jun 7 2021 at 6:48am

How is the Fed’s employment different from it’s prices mandate?

Now it could be the case that the best way to fulfill its employment mandate and its prices mandate is to target the trajectory of the CPE price level exclusively, or to target NGDP, or some other way. But is does have a dual mandate.

Evan Sherman

Jun 7 2021 at 12:17pm

You seem to be missing Scott’s distinction between “mandate to produce high employment” and “mandate to target employment”. He is suggesting that the best way to optimize high employment is not to specifically or directly target that as a goal but rather to maintain generally sound monetary policies.

(You are of course welcome to disagree with Scott’s claim on the merits, but from your response, it is not clear that you understood what the claim was.)

Scott Sumner

Jun 7 2021 at 12:18pm

Here’s the key difference. There is a natural rate of unemployment, whereas the inflation rate is a policy choice. Trying to target any variable that has a natural rate can lead to extreme cyclical instability.

This is why I favor nominal targets like NGDP.

Thomas Lee Hutcheson

Jun 5 2021 at 6:20pm

To the extent that Supplemental UI is holding down labor supply, what do you think of converting it unto a “job finders bonus to remove the constraint?

Scott Sumner

Jun 6 2021 at 12:04pm

I support that.

Ryan Greenblatt

Jun 5 2021 at 7:27pm

It seems to me that this argument assumes some level of rationality in covid risk aversion. However, this is clearly not the case; for instance, Democrats are more risk averse than Republicans (I assume this holds after accounting for age, region, activities, etc.). Age correlates with political associations which confounds this approach. Of course, this doesn’t obviously explain the 16-19 vs 20-24 differences.

Perhaps a cleaner way to look at the “Fear of the health risk associated with working” hypothesis would be to look at the employment data for Democrats vs Republicans of similar ages (or rural vs urban etc.)

Similarly, would it possible to look at the employment data for parents with older children vs parents with young children to test the “Lack of childcare” hypothesis?

I’m not sure if these datasets exist just yet. As well, these other approaches would introduce new confounding variables.

Scott Sumner

Jun 6 2021 at 12:05pm

See my reply to Daniel.

Michael Sandifer

Jun 5 2021 at 10:32pm

Very reasonable analysis. Right now, the markets are not expecting any lasting unintended overshoot in inflation, but it seems reasonable to think mistakes would be easy to make. Fortunately, comments from FOMC members seem to indicate that they are aware of possible confusing data over the short-term.

As always, I disagree that it’s necessarily a bad idea to consider real variables, though enough can be gleaned from nominal variables to get the job done.

Lizard Man

Jun 6 2021 at 9:14am

I would think that one of the primary differences between teens and the 20-24 year old age group would be college. I thought that a lot of teens decided to put off going to college because their parents became unemployed or lost income. And teens also were doing remote learning, and a lot of high school classes don’t require much work. So it would make sense that teens were working more. However, for people just a little bit older, they had already started college. College courses are more demanding than high school classes, and remote learning may have increased the difficulty. People who had already matriculated may have been reluctant to get a job because getting COVID might have prevented them from completing coursework. Also, they may not have wanted to skip a semester or two and delay their graduation.

Scott Sumner

Jun 6 2021 at 12:08pm

College students fall into both the 16-19 category and the 20-24 category. Those 20-24 year olds who work are probably mostly not in college.

Lizard Man

Jun 7 2021 at 12:38am

My larger point is just that the pandemic created a really unique situation that will make drawing meaningful inferences from comparisons of a population that is mostly in high school versus a population that has a greater percentage in college. And I do think that about half of US high school grad do matriculate now.

Of course incentives matter, and so it if the unemployment payments had no impact on employment, that would be surprising. But these are two demographics facing really weird incentives along a lot of different dimensions, so I think that inferences from their comparison will provide weak evidence. Not no evidence, just not strong evidence.

Scott Sumner

Jun 7 2021 at 12:20pm

Lots of people are in college from age 18-22, which overlaps with both groups. Add in that half don’t even go to college, and I doubt the overall difference is large enough to explain the huge difference in recent employment trends between the two age groups.

Evan Sherman

Jun 7 2021 at 10:19am

Not to step on the very compelling economic analysis and theorizing here – on econlib.org of all places! 😊 – but allow me to offer a squishy cultural dynamics theory in parallel:

People who have been forced, by government mandate or demand-side economic limitations, to hang around their homes for a year+ don’t want to go back simply because they don’t want to go back – and by definition, because they had to, they managed to find the means to support their new comfy yet affordable stay-at-home lifestyles. That is to say, people displaced from their out-of-home employment over the previous year discovered 2 things:

1) Hanging out at home is pretty comfortable, especially given the ever-increasing ability of markets to deliver goods and services (especially entertainment) to your home and sparing you the discomfort of dealing with people directly.

2) Especially if you’re single, childless, and healthy – even more so if you skew younger – one can live comfortably while spending much less money than one might otherwise make pursuing a painful, laborious job or career. (Adjusted for inflation,) things like housing and health care continue to become more expensive, but almost everything else – including sweet, distracting, time-consuming entertainment – is becoming cheaper. This was true before the pandemic, but people getting pushed out of the workforce all discovered just how true it has become. In this way, a lot of people discovered it all at the same time.

None of these are new phenomena of course. The increasing cheapness of most goods, the exponentially increasing availability and affordability of in-home entertainment, the modern alienation of the individual from community, etc. etc. are all long-term socio-cultural trends. But the pandemic did create conditions that prompted people to double down on those trends, so we shouldn’t be surprised if that’s exactly what happened.

(And none of the above is mutually exclusive with cold-blooded economic analysis. E.g. Ad hoc UBI by way of supplemented unemployment payment helps to fund the choice to stay home in an entertainment-rich bubble. But if we fail to consider the warmer/softer/harder-to-quantify socio-cultural factors, we are missing something that should otherwise be obvious.)

Matthias

Jun 8 2021 at 9:24pm

Even rent is cheaper, if you don’t have to live where the good jobs are.

Andrew_FL

Jun 7 2021 at 10:55am

Incidentally, this is the chart you wanted for 20-24 year olds

Scott Sumner

Jun 7 2021 at 12:22pm

Thanks. Why does FRED make that so hard to find?

Andrew_FL

Jun 7 2021 at 2:43pm

I don’t know, I had to get the population and employment series separately and combine them myself. The series is available from BLS, so it seems that FRED just isn’t scraping it.

Unfortunately, BLS’s data search system is wildly inferior to FRED.

Floccina

Jun 7 2021 at 11:55am

4. During and because of Covid, we found the family members including the wife were all happier without the wife working in the taxed economy but rather in home production for for in home consumption.

I’d often hear people say a wife need to work today to make ends meat to which I would say, not really there are people making less than you doing it.

Aaron M

Jun 7 2021 at 2:02pm

2. Lack of childcare, partly due to school closures.

I would imagine that you have seen this already, but Jason Furman, Melissa Kearney and Wilson Powell III attempted to estimate the impact the lack of childcare access was having on the job market recovery. Their conclusion was that childcare challenges “do not appear to be a meaningful driver of the slow employment recovery.” These are just one set of estimates, but they are interesting.

https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economic-issues-watch/how-much-have-childcare-challenges-slowed-us-jobs-market

Scott Sumner

Jun 7 2021 at 2:52pm

Yes, I did see that, and should have mentioned it in the post.

Larry

Jun 8 2021 at 3:45pm

Relative risk perception is skewed by age. That could help explain this: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.646558/full

Comments are closed.