Economists often speak of money being fungible. Thus if one country donates money to another with strings attached, the receiving country can often circumvent those constraints by diverting their own funds from one account to another.

A recent article in The Economist suggests that weapons and munitions are also fungible. The article begins by noting that South Korea refuses to exports military goods to Ukraine:

Under its Foreign Trade Act, South Korea is forbidden to export arms except for “peaceful purpose[s]”.

That seems pretty clear. But on closer inspection, it’s not obvious that the restriction has much force:

South Korea’s defence companies, which are known for producing lots of high-quality weapons rapidly at competitive prices, are booming on the back of the global demand for arms that the war has unleashed. The country’s defence exports increased from nearly $7.3bn in 2021 to $17bn in 2022. And a lot of them are going to countries arming Ukraine, ostensibly to allow them to replenish their depleted stocks. A recent deal with Poland, worth a reported 20trn won ($16.4bn), allowed the Poles to replace the howitzers they gave Ukraine last year.

In such circumstances, South Korea’s legalistic distinction between arming Ukraine and its allies looks moot. In reality, says Jang Won-joon of the Korea Institute for Industrial Economics and Trade, a government think-tank, South Korea’s view is that once its arms have been shipped, “it’s none of our business” where they end up.

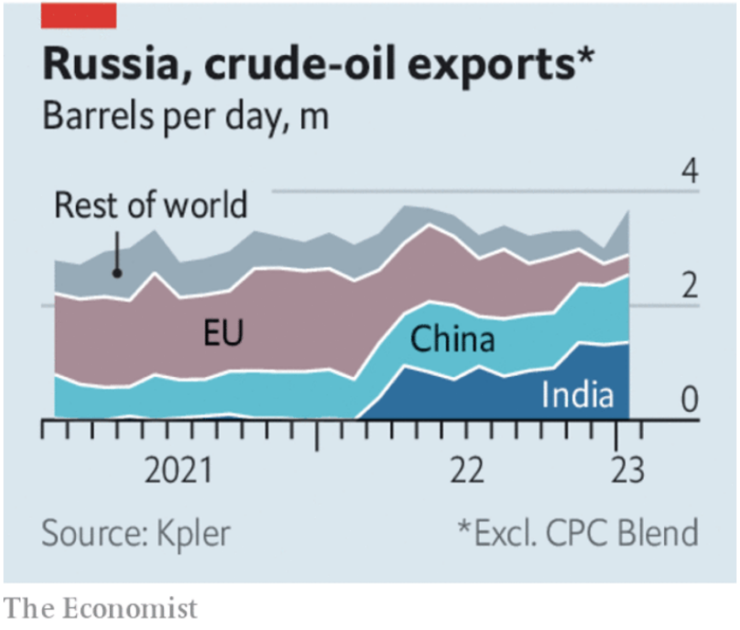

This also explains why economic sanctions against Russia have been less effective than hoped. If Europe stops buying oil from Russia, the oil can be shipped to India and China. Then, Europe can buy the non-Russian oil that was formerly going to India and China. The only impact is slightly higher transportation costs, as trade gets rerouted.

READER COMMENTS

Andrew_FL

Feb 19 2023 at 9:29am

China and India must be making enormous arbitrage profits reselling Russia oil considering the price differential. I think a chart of Russia’s income from oil exports would be more informative.

Jim Glass

Feb 19 2023 at 11:22pm

If Europe stops buying oil from Russia, the oil can be shipped to India and China. Then, Europe can buy the non-Russian oil that was formerly going to India and China. The only impact is slightly higher transportation costs,

Well, another significant impact is that the market price of Urals oil, after always tracking that of Brent, has fallen to $32/b below it — so much for ‘fungible at no cost’. And you may be underestimating the “slightly” higher transportation costs.

Scott Sumner

Feb 20 2023 at 8:11am

You may be right. But I recall reading many articles during 2022 that Russia’s energy revenues were actually higher than before, and that the sanctions had a disappointingly small impact. Were those stories inaccurate?

(To be clear, I support the sanctions.)

Jim Glass

Feb 20 2023 at 12:04pm

I know we are on the same side as to Putin’s war.

Before the war, 1/1/22, Brent and Urals were at $83. Just before the invasion oil prices started shooting up with Brent topping at about $123 in early March-early June. So yes, the Russians were reaping in the money on oil at that point, you remember correctly.

https://markets.businessinsider.com/commodities/oil-price

But now Brent is back down to $83, and Urals has separated from it and is about $30 below it.

https://www.statista.com/statistics/1298092/urals-brent-price-difference-daily/

So now for the Russians, not so much.

Comments are closed.