This is the full article that Charley Hooper and I had published in the Wall Street Journal 30 days ago.

Youth Pay a High Price for Covid Protection

Leaders’ greatest failure was not focusing on the elderly, who had lower costs and far greater benefits.

By Charles L. Hooper and David R. Henderson

Now that the Covid-19 pandemic seems to be abating, it’s a good time to look at lessons that observers have, or should have, learned. The list of mistakes is long, but the most glaring was the failure to understand and act on the virus’s propensity to attack the old and vulnerable. Policy makers failed, in other words, to understand the enemy.

Some clear thinking based on data that were available last spring would have led to two insights. First, the benefits of protecting the old and vulnerable exceed the costs.

For our purposes we are combining voluntary and coercive (e.g., government lockdown) nonpharmaceutical precautions—mask-wearing, hand-washing, quarantining, distancing and isolation of infected people—under the umbrella of protection. The benefits of protection include reducing the potential for death, pain, suffering and healthcare costs, along with reducing the chance of infecting others. But the main benefit of protection is that fewer people die from Covid-19.

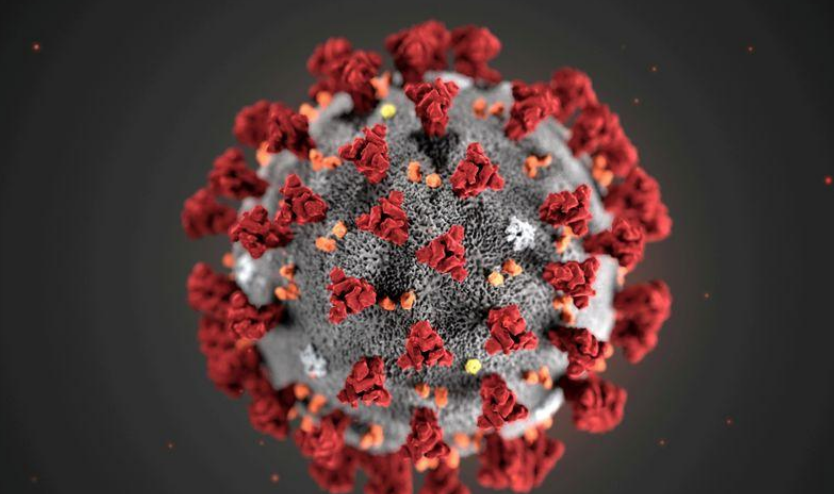

The infection fatality rate is the probability that a person will die once becoming infected, whether that person has symptoms or is unaware of the infection. The global average infection fatality rate of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, is roughly 0.23%. The average U.S. fatality rate is higher, probably 0.3% or 0.4%, because Americans are older and less healthy than those in most other countries. Underneath this average, the infection fatality rate increases exponentially with age. For an 85-year-old it may be 2,000 times as high as for an 18-year-old. This increase in the death rate by age is partly due to comorbidities, which increase with age.

The primary risk from SARS-CoV-2 is infection leading to death. Those who die lose years based on statistical life expectancy. A person’s expected years lost is equal to the infection fatality rate times life expectancy times probability of infection.

Had the Moderna, Pfizer /BioNTech, and Johnson & Johnson vaccines never been developed, the pandemic would have continued until natural herd immunity was reached. That’s the point in the life cycle of an infectious disease when enough of the population has immunity that the average number of people to whom a newly infected person passes the disease drops below one. In effect, those who are immune protect those who are still vulnerable, and the disease largely disappears. Herd immunity for SARS-CoV-2 would be reached after perhaps 70% of the population has been infected.

While perfect protection would eliminate the risk of infection, few people can practice it. Based on data analyzed by economists at the University of California, Berkeley, we assume that actual protection reduced the risk of infection by roughly half. Therefore, imperfect protection reduced the risk of infection for the average American from 70% to 35%.

We find that the benefits of protection are disproportionately higher for older people. Consider two extremes: the 18-year-old and the 85-year-old. If the 18-year-old dies, he loses 61.2 years of expected life. That’s a lot. But the probability of the 18-year-old dying, if infected, is tiny, about 0.004%. So the expected years of life lost are only 0.004% times 35% times 61.2 years, which is 0.0009 year. That’s only 7.5 hours. Everything this younger person has been through over the past year was to prevent, on average, the loss of 7.5 hours of his life.

Now consider the 85-year-old. If he dies, he will lose 6.4 years of expected life. The probability of dying, if infected, is much higher for him, about 8%. So the expected years of life lost are 8% times 35% times 6.4 years, which is 0.179 year—65 days. The benefits of protection, measured in life expectancy, are 210 times as high for the older person.

The costs of protection include reduced schooling, reduced economic activity, increased substance abuse, more suicides, more loneliness, reduced contact with loved ones, delayed cancer diagnoses, delayed childhood vaccinations, increased anxiety, lower wage growth, travel restrictions, reduced entertainment choices, and fewer opportunities for socializing and building friendships.

In a 2020 study for the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Eric Hanushek and Ludger Woessmann estimate the loss to lifetime income for individual students to be 6% (assuming schools were closed or reduced for the equivalent of 67% of a year). Given U.S. median lifetime earnings of $1.7 million, that 6% translates into $102,000 per student. This loss of income from protection disproportionately affects younger Americans. Those who are retired are largely unaffected.

Assuming that reduced lifetime earnings are the only costs and reduced life-expectancy losses are the only benefits, the 18-year-old faces a cost of protection of approximately $102,000 and a benefit of 31% of a day. Would you pay $102,000 to live an extra 7.5 hours? What 18-year-old values his time at $13,600 an hour? The costs for the 85-year-old are close to zero (remember, this person is probably retired) and the benefit is 65 days. To be sure, there are other costs for both groups. For the 18-year-olds, that makes protection even less of a good deal. The 85-year-old, by contrast, may be willing to endure more risk for the sake of time with loved ones.

In hindsight, the 18-year-old should have invested only minimally in protection; the costs exceeded the benefits. Work, school, sports and socializing should have continued, perhaps with some minor precautions. But the 85-year-old should have worked hard to protect himself—the benefits exceeded the costs.

SARS-CoV-2 is highly discriminatory and views the old as easy targets. Had policy makers understood the enemy, they would have adopted different protocols for young and old. Politicians would have practiced focused protection, narrowing their efforts to the most vulnerable 11% of the population and freeing the remaining 89% of Americans from wasteful burdens.

Mr. Hooper is president of Objective Insights, a firm that consults with pharmaceutical clients. Mr. Henderson, a research fellow with the Hoover Institution, was senior health economist with President Reagan’s Council of Economic Advisers.

READER COMMENTS

Thomas Lee Hutcheson

Jun 3 2021 at 6:46pm

The analysis fails to account to consider what changes in behaviors of younger people are cost effective in reducing the spread of the disease to others and how those changes could have been incentivized. Optimal policies have to take account both or what different people with different risks of infecting and becoming infected should do and least cost of carrying out those policies.

Stepping back, it fails to consider a screen and isolate strategy that would have reduced spread and allowed the restrictions on commercial and social interactions to be concentrated on the infectious so that the costs of such restrictions on everyone else could be minimized.

Andre

Jun 4 2021 at 10:11am

” it fails to consider a screen and isolate strategy that would have reduced spread and allowed the restrictions on commercial and social interactions to be concentrated on the infectious”

Just to confirm.. Are you saying policymakers could have developed a policy that somehow is capable of restricting the infectious?

Thomas Lee Hutcheson

Jun 4 2021 at 10:41am

I think that if it had been cheep and easy to get tested, many of those who discovered they were asymptomatically infected would have isolated themselves, especially if all employer had paid sick leave days (something I think ought to be subsidized on public health grounds). That self isolation would certainly have slowed the spread of the disease AND reassured others that they need not isolate themselves to prophylactically prevent infecting others. The lower spread would, in turn, have led to less “self protection” avoidance of social and commercial activity. I cannot be sure, of course that this would have been worth he casts of establishing the screening test infrastructure, but I think it would.

Christophe Biocca

Jun 4 2021 at 11:49am

The testing story is definitely worth some exploration, though in the case of the US there was the absurd policy to block laboratory-developed tests, combined with the CDC failing to get their own test out quickly. Far from making tests available, early federal efforts were effectively restricting access, out of a fear of people getting low-quality tests.

The rules that caused this were relaxed in November but that was entirely due override by appointees in the executive branch, and unlikely to persist through to the next pandemic.

Thomas Lee Hutcheson

Jun 5 2021 at 5:46am

I’m surprised that journalists have not looked into the decision-making process; the restrictions on testing have been reported, even pretty early on, as errors.

Andre

Jun 4 2021 at 10:04am

Yes, those most likely to lose were those who could most easily lock down and in most cases weren’t working anyway. By contrast, the enormous group to whom Covid poses no threat were forced to give up a year of their lives.

The asymmetric impact of Covid was obvious in February 2020 – we already had aggregate data that showed the multiple-orders-of-magnitude gulf between the real threat to the elderly and the next to nonexistent threat to the young. It’s still there on Worldometers for everyone to see. This has all been one big panic based on “what ifs” that belied the data we already had weeks before DeBlasio was still exhorting people to go out on the town.

Thomas Lee Hutcheson

Jun 4 2021 at 10:49am

I’m well persuaded that our aggregate response to the pandemic was not optimal even based on what was know at the time each less than optimal policy was made. I just do not understand exactly what alternative set of policies Henderson advocates. “More” protection of the old and “less” of the young is pretty vague.

robc

Jun 4 2021 at 12:45pm

Why does he need to suggest a policy? Why couldnt each at risk person have created their own policy?

Thomas Lee Hutcheson

Jun 5 2021 at 6:00am

Because “public” health is about doing thing a at a scale that individuals have inadequate incentives and information to do. Some people needed to do some things to avoid infecting others, things that are not exactly the same as what they should do to prevent themselves from becoming infected using only information from their own experience. Public health is about coming to understand and disseminating those things and devising cost effective policies to incentivize people to do them.

Henderson clearly does not think that the set of policies actually followed were the best. I would like to know his views in a bit of detail — beyond “protect the old more restrict the young less” — what he thinks a better set of policies would have looked like.

AMT

Jun 5 2021 at 12:07pm

“Why couldnt each at risk person have created their own policy?”

Externalities.

David Henderson

Jun 4 2021 at 11:13am

Well put, Andre.

A friendly (hopefully you’ll take it that way) amendment to one of your sentences:

By contrast, the enormous group to whom Covid poses very little threat were forced to give up big parts of a year of their lives.

Andre

Jun 4 2021 at 12:07pm

I absolutely take it as a friendly, David.

I’m not sure I’m prepared to agree with the amendment, though. Do you have evidence that any healthy 5-15 year olds died? I just haven’t seen any yet.

Young people with comorbidities needed to lock down just like everyone else at risk – which includes pretty much everyone on health medications, including half of the population over 50.

David Henderson

Jun 4 2021 at 2:07pm

Thanks, Andre, for your clarification that the enormous group you mentioned were young people with no co-morbidities. That didn’t come across in your original statement, but I can see how it’s consistent with the detail that you added.

Like you, I haven’t seen such data. The CDC, unfortunately, does not break out for the public the percent of fatalities of young people who have co-morbidities.

James

Jun 5 2021 at 10:43am

Thanks for this article. It’s amazing how little discussion there has been of this obvious, huge disparity.

Arguably there should be a COVID Reparations tax imposed on old people, with the proceeds distributed to young people.

AMT

Jun 5 2021 at 12:23pm

Interestingly, you “forgot” that it was ALSO to prevent the transmission that would happen to others who are more vulnerable. It’s always amusing to see an “economist” who completely ignores externalities, not to mention the substantial costs of the illness itself (death is obviously not the only harm from covid; I previously mentioned this on one of Bryan’s posts). I’m not sure your theory on how the virus spread to nursing home residents…apparently it couldn’t have been from the younger people working there. Maybe the nursing home residents, dependent on others, should have taken more precautions!

Ugh, do we need to quote a study that is facially absurd? “Let’s just incorrectly assume schools were CLOSED OR ‘reduced’ for 2/3 of a year, because remote learning means closed!”

If you’re going to make an argument, please at least try to make it a good one, without such farcical assumptions and glaring holes.

Comments are closed.